Price of medicines: walls of abusive patents are standing in the way of competition

Patrick Durisch, 30. August 2024

©

Teacher photo/Shutterstock

©

Teacher photo/Shutterstock

A new drug is not protected by a single patent, but by dozens, or sometimes even more than a hundred patents, commonly called “patent thickets”. These are also filed over a period of time, which means that the duration of a product’s monopoly often easily exceeds the theoretical 20 years foreseen by the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Agreement on Intellectual Property (TRIPS). A strategy of endless accumulating patents described as “evergreening”.

A distinction should be made between two types of patent:

primary patents relating to the substance(s) and filed early in the development phase,

and secondary patents filed just before or during the marketing phase, which extend the period of monopoly but without any real therapeutic added value.

While any patent is an exception to the free market, secondary patents are undoubtedly the ones that have the most impact on competition and prices – especially since they have proliferated in recent years, particularly in the United States, where they are more easily granted.

Secondary patents granted en masse

Every year Switzerland boasts of being one of the “most innovative countries”, based simply on the number of patents filed. However, at least as far as drugs are concerned, the vast majority are unjustified and have little to do with real progress. The big pharmaceutical groups quickly realised the financial advantages they could gain from the abusive use of patents to block the way of their competitors. At the other end of the supply chain, patients have to pay high monopoly prices for their treatments for longer, without any valid justification.

It should be remembered that a patent is an exclusive right that allows the holder of the invention to prohibit third parties from manufacturing and marketing it. But it is a territorial right: if a pharmaceutical company wants to protect its drug in several countries, it has to apply for it in each of them – except in Europe, with the European Patent Office (EPO) bringing together 39 countries, including Switzerland, and having a centralized procedure that applies simultaneously in all these jurisdictions.

It should also be remembered that an invention must meet three general requirements to be patented: (1) be novel; (2) involve an inventive step; and (3) be capable of industrial application. A patent application for a drug is therefore not judged on the basis of the treatment’s benefit – but only on the basis that it is a “new invention” that is taken into account, even if it is only a minor modification of an already existing product.

The TRIPS Agreement leaves a great deal of leeway for WTO member states to decide which invention deserves a patent or not, as long as the three requirements are met. Therefore, depending on the legislation in force and how meticulously the applications are examined, patents are either granted en masse (as in the United States), in a slightly more restricted way because they are sometimes opposed (as in Europe), or sparingly because of more restrictive clauses aimed at avoiding rewarding pseudo-innovations that jeopardize the right to health (as in India). These approaches have very different consequences in terms of competition and access to medicines, with generics arriving on the market more or less late, depending on the country, and sold at lower prices.

©

2024 Bloomberg Finance LP

©

2024 Bloomberg Finance LP

United States – a real paradise for the pharma industry

As in numerous other industries, the United States sets the tone in the pharmaceutical sector. With a turnover of more than $600 billion annually, USA alone accounts for more than half of the global pharmaceutical market. This is a key theatre of operation for Roche and Novartis, which are ranked second and eighth respectively in the world in terms of sales in 2023.

The Basel-based giants are long-time members of the powerful pharmaceutical lobby in the United States (Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America or PhRMA), which is well established in Congress and the White House. The Novartis CEO is even chairing it since 2023. In the United States, pharmaceutical companies benefit from numerous incentives and major tax benefits in the field of research, as well as a very generous patent policy and a legal system conducive to initiating litigation at all costs. The marketing authorisation procedure is also closely linked to the status of patents, which is not the case in Europe. And the icing on the cake: there is currently no proper governmental price control policy.

Therefore, large corporations seek to launch their new products first in the United States in order to be able to protect their invention for as long as possible (sometimes for 40-50 years) and obtain a very high price on the United States market, which they will then use as a basis for negotiation in other countries, for example in Europe, where price controls are slightly tighter.

Entresto – Novartis’ blockbuster

To highlight how the pharmaceutical sector is exploiting its position of strength to squeeze out the competition, we looked at the case of Novartis’ Entresto. After a rather slow start, this treatment for heart failure, launched in July 2015 in the United States and shortly after in Switzerland and the rest of Europe, saw its sales explode in 2021, after obtaining an extension of indication for different types of heart failure. In Switzerland, its annual sales more than doubled from CHF 18 million to more than CHF 39 million between 2019 and 2023, according to figures from the health insurance company Helsana. In 2023, Entresto generated the group’s highest revenue globally, posting a figure in excess of $6 billion (around 13% of total sales). In just eight years, Novartis has already raked in more than $20 billion in sales from this product.

Its official price in Switzerland for a month’s treatment is about CHF 130 francs (CHF 2.3 per tablet). As is often the case for medicines, it is four times higher in the United States: $668 per month, while it is somewhat cheaper in India (10,200 rupees or about CHF 103 per month). This price may seem derisory compared to that for cancer drugs, but the margin remains substantial due to high demand and an extremely low production cost of CHF 0.13 per tablet.

In addition, Entresto is a combination of two old substances, including valsartan, which has been a hit for Novartis as a treatment for hypertension for the past 25 years under the brand name Diovan, generating more than $65 billion in revenue so far. From a commercial perspective, Entresto is therefore an attempt by Novartis to extend the staggering sales of its predecessor Diovan, while expanding its target audience to patients suffering from heart failure. In a nutshell, it has hit the jackpot.

Novartis has long since recouped its investment in developing Entresto, generating an enormous profit margin into the bargain. However, the Swiss giant is still hungry for more and initiated a legal saga in 2019 in the United States and India with a view to delaying the market entry of generic competitors for as long as possible. This is where secondary patents come into play.

©

2022 Halawi/Shutterstock

©

2022 Halawi/Shutterstock

A flurry of frivolous patents

Novartis has been granted at least 13 patents on this product in the United States, theoretically ensuring market exclusivity for almost 40 years, double the standard provided for by WTO rules (see table below). Apart from the number involved, another striking aspect is the type of patents and their filing dates. The drug, a combination of two substances, has remained exactly the same from the beginning. The only changes made have been to indication, dosage and other aspects such as its method of use. However, on each occasion, new secondary patents have been filed and granted. Where are the therapeutic benefits from this? Virtually none. On the other hand, the monopoly period has been extended by 18 years, until 2042.

In Europe, there are at least nine patent applications, three of which are under examination by the EPO. Only three patents are valid to date (see table below). Entresto’s primary patent expired in 2023, but its protection has been extended in Switzerland until January 2028 by the Swiss authorities. Entresto’s protection in Europe, with all the patents granted taken together, theoretically runs until May 2036, but if the three pending applications are successful, this period will then be 40 years – double the WTO standard. Two secondary patents were revoked (one by the proprietor and the other following oppositions), demonstrating that they should not have been granted if they had been scrutinized more closely by the EPO.

The landscape is different in India, where five patents have been granted on Entresto (marketed under the brand name Vymada), four of which are secondary (see table below). The primary patent (expired in January 2023) was challenged in court in vain in 2019 by four generic manufacturers. The second patent, filed in 2006, was the subject of nine oppositions before it was granted, as authorized under Indian law, but it was eventually granted. New appeals were then filed, and proceedings are still pending. As for the other three patents, they could well be challenged later in court by Indian companies. At stake are delays to the marketing of more affordable generic equivalents (at least 50% cheaper than the original) and improve access to this product in a country where the majority of patients pay for medical treatment out of their own pockets.

With its primary patents expired and more than $85 billion generated in 25 years, thanks to Diovan and Entresto, it’s time for Novartis to finally make way for generic products. But the Swiss corporation does not care about this and continues to systematically take legal action to block its competitors based on its abusive secondary patents.

A flurry of legal actions in the United States

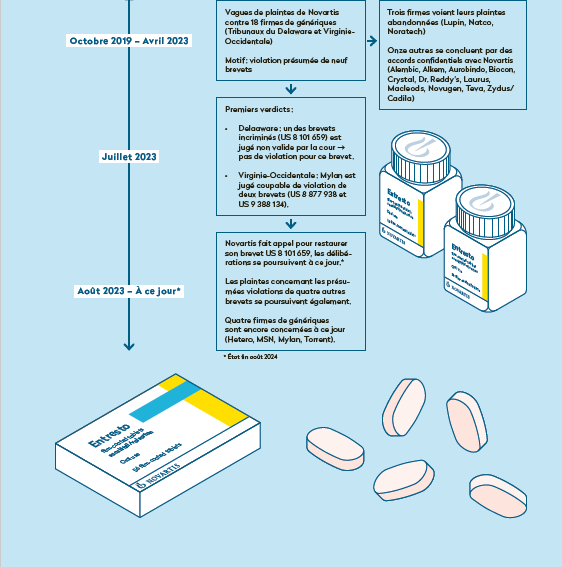

Our extensive investigations have allowed us to trace the numerous complaints Novartis has filed in the United States for alleged infringement of its Entresto patents, based on court documents that we have been able to access (see timeline below).

One striking observation was at the origin of this investigation: over the last decade, Swiss pharmaceutical companies have taken legal action almost routinely in the United States or India with the aim of excluding – or at least significantly delaying – competition, whether for Entresto or Gilenya (used to treat multiple sclerosis) regarding Novartis, or for Esbriet (used to treat pulmonary fibrosis) or its treatments against breast cancer (Herceptin in the past, Perjeta currently) regarding Roche. We have examined each of these cases, but we will focus here on the emblematic case of Entresto.

In the United States, Novartis filed no less than 25 complaints for alleged infringement of nine of its patents on Entresto between October 2019 and October 2022 against 18 pharmaceutical companies that had signalled their intention to market generic versions. It should be noted that all these complaints, prior to marketing, were purely preventive. At the time, the companies involved did not sell any generic form of Entresto on the US market, but had simply initiated the lengthy approval process with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in order to be ready when commercial exclusivity ends. These preventive litigations are a particular feature of United States law, known as “patent linkage”, which links the status of patents to the marketing authorization procedure. Fortunately, this situation does not exist in Europe. The role of a medicines agency such as Swissmedic is to ensure that the treatments to be approved are safe and effective, not to play the role of competition watchdog.

Of the 18 companies sued by Novartis, three have had the complaint against them dismissed due to no infringement. Eleven others have reached a negotiated confidential settlement with Novartis, probably by undertaking not to market their generic product before a date agreed between the parties, in exchange for a stay of proceedings.

This type of agreement generally takes two forms in the pharmaceutical sector:

granting a licence against the payment of royalties, valid from a given date;

“pay-for-delay”, a traditional tactic, especially when a patent is precarious. The manufacturer of an original drug then pays a specific amount to a competing firm in order to encourage it to postpone the launch of its generic product. This practice, which is also common in Europe, has been strongly criticized on several occasions by the competition authorities. It is also very expensive for healthcare systems, since the drug continues to be sold at a high price until a generic product arrives. In the case of Entresto, it would seem that licensing agreements have been concluded, although this cannot be established for certain since the court documents are either sealed or redacted.

Timeline about the complaints filed by Novartis in the USA for alleged Entresto patent infringement. Download PDF here.

In July 2023, the only two verdicts to date in this legal saga were delivered:

In the first case, after four years of litigation with a lot of experts and lawyers, one of the nine Entresto patents involved was invalidated by the Delaware Court (In re: Entresto (Sacubitril/Valsartan) Patent Litigation, Case No. 1:20-md-02930, US District Court of Delaware, 21/07/2023). Novartis lodged an immediate appeal with the federal court (proceedings are pending).

In the second case, the verdict was delivered by the West Virginia Court in favour of the Swiss corporation for confirmation of an infringement of two patents by the company Mylan. The latter has not lodged an appeal and no other information can be gleaned from the court documents, but it’s conceivable that a confidential settlement has been reached. It should be noted that it was decided on the basis of half a molecule of water in the chemical formula between Novartis’ original product and Mylan’s generic product when it came to tipping the scales of justice one way or the other, according to the court’s verdict issued on 6th July 2023. This highlights the complex nature of the proceedings, but also the considerable time that pharmaceutical giants can gain thanks to lodging such legal complaints.

At the moment, Novartis’ complaints “only” concern four companies and relate to an alleged infringement of four patents (five if Novartis wins its appeal). It is unclear when the next verdicts will be delivered, but the proceedings could still take a long time.

Between May and August 2024, seven generic versions of Entresto finally received the green light from the FDA, but this approval does not yet mean that they will soon be able to be marketed and made available to patients. Novartis is once again taking legal action on 30th July, this time with a civil complaint against the FDA for breaching its approval procedures (Novartis Pharms Corp. v. Xavier Becerra ¬ Robert Califf, Case No. 1:24-cv-02234, US District Court of Columbia, 30/07/2024). Although the court denied Novartis' motion to stay FDA's approval in the first instance, these companies could well see the marketing of their generic Entresto in the United States further delayed, depending o the final outcome of this case and of the other pending patent litigations.

In the meantime, Novartis can continue to rake in billions of dollars more from its frivolous secondary patents – a perfect example of “evergreening” and a real racket run at the expense of patients and of social insurance.

Legal saga in India too

As India has always refused to introduce a system linking the status of patents to the approval procedure (“patent linkage”), generic versions of Vymada (the Entresto brand name in India) were granted marketing authorisation in 2019. Prospects are indeed juicy, with a cardiology market estimated at CHF 2.5 billion and overn 650,000 new cases of heart failure diagnosed every year. In 2019, Novartis sued the four Indian generic manufacturers involved, who then countersued by requesting the revocation of the primary patent (IN 229051). The Delhi High Court finally ruled in favour of the Swiss corporation in 2021, prohibiting local companies from manufacturing and marketing their generic versions, at least until the expiry of the primary patent (January 2023).

Attention then turned to the second, secondary patent (IN 414518), which had been granted in India despite nine well-argued pre-grant oppositions, and which extended Novartis’ market monopoly until November 2026. Several generic companies therefore took legal action, as early as 2022, to try to revoke this secondary patent after it had been granted. Initially, the Delhi High Court suspended the secondary patent in question in January 2023, before reversing its decision a few days later, confirming its validity. What followed was even more confusing, between a counterattack by generic product companies to try to revoke the secondary patent and appeals by Novartis on which – as far as we know – no verdict has been delivered yet. And the matter of the other three secondary patents, with a theoretical term of protection until February 2037, has not been resolved either.

Even if this has not been the case so far for Entresto, Swiss pharmaceutical companies have, in the past, broken their teeth several times with these pre-grant patent oppositions. Starting with the symbolic case of Novartis’ cancer drug Glivec, which had its primary patent refused by the Indian authorities. Only a few countries, such as India or Thailand, use this legal flexibility enshrined in the WTO agreements. Europe (with the exception of Portugal) and the United States do not provide for these pre-grant procedures, as they irritate Big Pharma by running counter its business. In its bilateral free-trade agreement concluded recently with India, Switzerland has also managed to undermine these opportunities to intervene at an early stage of the procedure. This is very bad news in terms of access to medicines and public health.

Novartis sues Biden administration

In the United States, the Entresto case is not confined to a tug-of-war between pharmaceutical companies. Novartis has also pressured the FDA directly to ensure that the US drug watchdog does not approve any generic versions of its product during its period of market exclusivity, constantly seeking to gain more time.

In September 2021, the U.S. Department of Justice announced the opening of a civil inquiry into possible remuneration paid to doctors in order to push sales of Entresto. Novartis has already been in the firing line of the US authorities for marketing practices. In 2020, the Basel-based company had to pay a fine of more than $670 million to settle a kickback case involving several of its products (including Entresto’s predecessor Diovan). No further communication regarding the latest investigation into Entresto has been made public since.

In August 2022, Novartis got a dose of its own medicine. The company was sued by the universities of Michigan and South Florida for a potential infringement of their patent covering a manufacturing technique used to produce Entresto. The outcome of this case is not known, but it may have been settled by Novartis paying financial compensation to both universities.

Finally, through the adoption of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), achieved after a major effort by the Biden administration in August 2022 up against the powerful pharma lobbyist PhRMA, Medicare public insurance (for those aged over 65) has obtained, for the first time in history, the possibility of directly negotiating the price of the most expensive treatments in terms of their coverage. A year later, the list of the first 10 drugs to go through this new procedure was made public, with a new regulated price applicable from 2026. These priority products include Novartis’ Entresto, which cost Medicare about $2.9 billion in 2023 for some 600,000 patients. Medicare aimed to lower its price by at least 25%.

The response was not long in coming. Novartis brought a lawsuit against the United States Government on 1st September 2023, calling this reform unconstitutional. The Swiss corporation believes that this is tantamount to “expropriation of private property” and risks “jeopardizing research for innovative medicines”.

All the Big Pharma players concerned, as well as their umbrella organization, have also taken the matter to court, crying wolf. Even Roche, whose name does not appear in this first selection, has protested, threatening to delay the marketing of new vital products due to this reform. As is often the case, Big Pharma is putting up a united front to avoid any unfortunate precedent that could go against its business model – all the more so in its land of milk and honey, the United States, where companies have until now been all-powerful in terms of setting prices.

However, research carried out by NGO Public Citizen indicated that in 2022, the pharmaceutical companies involved in these negotiations invested an average of $10 billion more in share buybacks, dividend payments to shareholders and executive compensation than in research and development (R&D) – in the case of Novartis, it was $18 billion versus $10 billion for R&D. This puts their threat to innovation very clearly into perspective.

Novartis has finally resigned itself to entering into negotiations despite its pending complaint. The reason for doing so is that taxes could rise to 95% of the turnover of the relevant product if it did not do so. It was also able to submit a counteroffer to the price suggested by Medicare. The latter eventually The latter eventually unveiled the newly negotiated prices mid-August 2024, indicating a more than 50% reduction of Entresto’s price ($295), which prompted Novartis to publicly criticise them. While two other Big Pharma complaints have already been dismissed, Novartis’ complaint against the Biden administration is still pending.

Switzerland must take action against the abusive use of patents

“Evergreening” or the accumulation of abusive secondary patents on therapeutic products is a stumbling block to access to medicines, as well as a huge additional cost for patients and society. In Switzerland, medicines account for almost 1 in 4 Swiss francs of compulsory health insurance expenditure, 75% of which is attributable to patented products, according to an analysis by the Federal Council. What proportion of these are frivolous allowing a monopoly to be maintained – and the high price that goes with it – much longer than the duration provided for by WTO rules? It is impossible to quantify this, due to the lack of precise studies on the subject in Europe. However, we can bet that this is a high proportion, if we compare the limited number of new drugs launched on the market each year with all the pharmaceutical patents filed.

According to the US NGO I-MAK, patent abuse involving the 10 best-selling drugs in the United States amounts every year to dozens billions of dollars in additional costs for the healthcare system. The United States Government has finally spoken out against these patent thickets that feed Big Pharma’s greed, and is considering reforms. Is the tide finally turning on the other side of the Atlantic?

Switzerland, for its part, systematically refuses to act against intellectual property abuses concerning access to medicines in multilateral forums, as we saw during the COVID crisis (at the WTO) and currently in the context of the pandemic accord, which is being negotiated at the World Health Organization (WHO). Worse still, the Swiss authorities are seeking to strengthen intellectual property further or, if they fail, to limit the room for manoeuvre of lower-and middle-income countries in combating abuses, as we saw as part of the bilateral free trade agreement concluded in March with India.

As a member of the EPO, which grants European patents for pharmaceuticals, Switzerland could act at this level to ask for a more meticulous examination of applications. Even though Europe grants fewer than the United States, far too many undeserved patents are still granted, as illustrated by our 2019 opposition to the cancer treatment Kymriah, following which Novartis revoked the disputed patent before any adversarial debate. It is better to avoid abusive patents being granted, rather than having to contest them in long and costly litigation afterwards. To achieve this, it is essential to define and enforce stricter patentability rules.

Switzerland had long opposed patents on medicines, considering them to be an essential good unlike other items, before radically changing its stance. Without going as far as to make such a U-turn, why not start by tackling the abusive practices of its pharmaceutical companies, which have harmful consequences for health and public finances in Switzerland just like elsewhere?