Mourning for the sun

Adrià Budry Carbó and Robert Bachmann, 7. November 2022

©

Saeed Khan / AFP

©

Saeed Khan / AFP

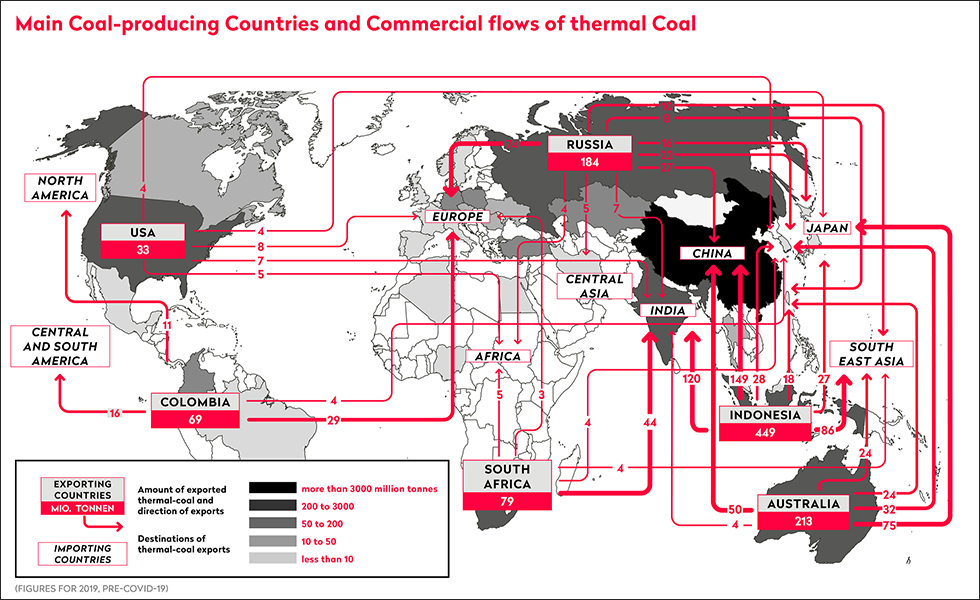

In another age coal comprised the vast majority of the energy consumed by Victorian Britain. On the global level, King Coal retains his crown because he continues to represent a quarter of the energy mix and remains the most-used resource for producing electricity (over 35 percent according to the International Energy Agency1). As a result, hoping for the possibility of an immediate ban on coal is simply wishful thinking. “We’re not talking about tobacco”, warns Lars Schernikau. “Coal is everywhere, all countries have used it at one point or another. Its energy is in a third of everything that we consume globally. It’s no solution unless we want to return to being cavemen”.

It also seems that everything is going in coal’s favour. When the European Union (followed by Switzerland) declared an embargo on Russian coal, its price skyrocketed – to the delight of mining companies. When Russia shuts off the gas, it will once again be coal – its direct substitute – that will benefit.

The perfect storm

“Recent months have been completely crazy. The European electricity plants are buying as much non-Russian coal as possible and are prepared to pay a very high price to outbid the Asians”, underlines Alex Thackrah of Argus Media, the reference agency that sets the indices for the spot markets.

In April, the data provided to Public Eye by Argus Media showed an increase of over 71 percent of coal imports to Europe to reduce to nearly zero the level of Russian imports.

From January to August 2022, Europe imported some 63 million tonnes of thermal coal against 45.2 million tonnes for the same period in the previous year, according to maritime data collected by Argus Media. The main winners are producers in Colombia, South Africa and the United States – and Australia, which even opened a new export route to Europe.

Despite the currently sky-high prices, the sedimentary rock remains the most accessible energy in the world. This is the great advantage of coal as a resource. “The substance brings heat, fridges and connectivity to disadvantaged populations. There is no better development lever”, states a trader who has worked in the sector for around 15 years.

Europe made no mistake in that regard. Everywhere, strenuous efforts are being made to accumulate coal stocks for a winter that is set to be long and of strategic importance for the containment policy towards Russia. “Over the past six months, the focus has been on energy security. The deadline to decommission European plants will probably be postponed”, Alex Thackrah was already predicting in March. And since then, Germany has done just that. Faced with challenges, Berlin – which had predicted that it would fully phase out coal by 2030 – decided in June to reactivate its coal-fired power plants. “Uncertainty reigns” concludes Alex Thackrah. The trend is set to continue at least for two winters. The planning horizon has become limited to just the coming season.

©

Alamy

©

Alamy

The beneficiaries will be EPH group, which owns two lignite mines in eastern Germany, and numerous coal-fired power plants that were previously due to be decommissioned. The tax authorities in Zug, the canton where EPH set up its commercial division EP Resources in 2019, also stand to benefit. As was confirmed in early August, operations will be relaunched in two coal-fired power plants. The first, Mehrum, situated in Germany’s Lower Saxony, had been decommissioned in late 2021. The second, Emile-Huchet, in the French Great East region, was due to be reconverted, in part to produce hydrogen. “Luckily these assets still exist”, responded Tomáš Novotný, head of EPH’s dry bulk division and member of the Board. “If Putin had attacked Ukraine three years later, we would have been, in energy terms, practically slaves of Russia. These are the arms the German gas lobby pushed us into.”

In the hands of the billionaire Daniel Křetínský, the Czech group EPH once specialised in re-purchasing at low prices east European and French power plants, including Émile-Huchet. This attracted significant criticism from both NGOs and the energy sector. Tomáš Novotný savours the revenge: “We retook these assets that no one wanted to transform them into modern power plants. We were asked to decommission them in the next two to three years, but the authorities came back to us to ask us to ensure energy security.” However, EPH did not wish to confirm its level of lignite production or communicate its portion of coal negotiated on behalf of third parties.

The United Kingdom, France, Italy, Austria and the Netherlands also took measures aimed at reactivating their coal-fired power plants or increase output. The list is not exhaustive.

Remembering our promises

Despite international pressure, the coal sector continues to enjoy its greatest hour. Glencore is among the ‘to the bitter end-ists’. In June 2022, the multinational announced that its profits were set to exceed predictions by a billion USD – to reach USD 3.7 billion in a single semester – due to the excellent performance of its coal business. The extraction of coal alone will generate more than all the other departments in the group, namely USD 8.9 billion. In an average year, Glencore makes 10–15 percent of its profits from the sedimentary rock. When global prices skyrocket, as they did in 2022, this can increase to over 50 percent. A Financial Times editorialist called this “Glencore’s deadly addiction”.

Despite the discontent of some of its investors, the group has always refused to separate from its mining assets – quite the opposite. In January 2022, it bought the shares of its associates BHP and Anglo American in the Colombian Cerrejón mine, the largest mine in Latin America, for USD 588 million. Shortly before his departure, Ivan Glasenberg had declared that the new boss of Glencore should resemble himself. He got what he wanted. Like him, Gary Nagle is a white South African who built his career on coal. He is sometimes nicknamed “mini-Ivan” and came from the ranks of Glencore, where from 2000 he was responsible for the company’s mining assets – like Ivan before him.

“What do you think about your plans to shrink the output of the coal business? What would it take for you to delay the ramp-down and, ultimately, make investments to give the world the energy it needs in the short term?” asked an analyst at Glencore’s half-year results presentation in early August2 Faced with the world’s energy needs and the financial boon they represent, energy and social concerns appear to have been relegated to a secondary order of importance. Or, as the Bloomberg specialist Javier Blas puts it, “ESG is so, so, so yesterday” (i.e. environmental, social and governance procedures are outdated).

For COP 26 negotiators who said they wanted to “consign coal to history”, the task appears harder than expected. The war in Ukraine and threats of blackouts that once again weigh over western economies have awoken old demons. “No one is prepared to lower their standard of living. And who will go and tell the Indians or Vietnamese, who aspire to live like us, that they shouldn’t bet on what created our prosperity?” a representative of the trading house was already telling in 2019. The problem is that renewable energies are still far from picking up the baton. Everyone has their own idea: liquified natural gas, hydrogen and even nuclear – taboos are about to be broken across continental Europe. “Coal is the cheapest option in economic terms, but it is politically onerous”, summarises a coal trader.

Low-cost power plants

Power plants have been reactivated in a Europe that (practically) no longer knows what coal mining is. What’s more, new power plants are being built, bolstered by foreign capital. Thus, within the framework of its large Belt and Road Initiative, China – through its development banks – is funding the construction of “low cost” coal power plants in Bangladesh, Pakistan and Vietnam, countries where coal is set to have a bright future.3 Bangladesh, for example, plans to increase the share of coal in the country's energy mix from 8% to 17% in the coming months. "It saddens me, but it’s the lowest common denominator that rules in this market” notes a former trader. “The safety standards are set by those who charge the lowest prices. We’re looking to produce energy at the lowest cost, which will have the greatest impact on our environment.”

These “soot roads” as they are nicknamed by the journalist Mickaël Correia in his book Climate Criminals4 promise to imprison economies in a carbon-intensive environment for decades to come, while causing the marginal cost of alternatives to increase. “In Europe or the United States, power plants have on average a life of 40 years. In Asia, there are power plants of over 1400GW [Ed.: The equivalent of the power of 1000 nuclear power plants like that of the Swiss city Leibstadt or 700 times the power of the Grande-Dixence hydro-electric dam in the Valais] which are on average 11 years old. They are far from going into retirement. It’s the Achilles Heel of the battle for the climate” summarises Fatih Birol, the Executive Director of the International Energy Agency in the same book.5

On the Old Continent, one could also cite the great authors of the 19th century to recall the negative externalities associated with the production and combustion of coal. Charles Dickens tackled the subject in his novel The Old Curiosity Shop6: “On mounds of ashes by the wayside, sheltered only by a few rough boards, or rotten pent-house roofs, strange engines spun and writhed like tortured creatures; clanking their iron chains, shrieking in their rapid whirl from time to time as though in torment unendurable, and making the ground tremble with their agonies.”

Its "indirect" emissions generated by the production, transport and combustion of coal from companies registered in the country are enoug to turn Switzerland into a giant mountain of burning coal:

In Switzerland alone, “indirect” emissions represent nearly 5.4 billion tonnes of CO2 per year.

Once again, Charles Dickens provides the best description of the soot exported from Switzerland’s financial hub: “Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot […] as big as full-grown snowflakes […] one might imagine, for the death of the sun”.7

Nevertheless, Lars Schernikau insists “If we were to leave behind fossil fuels that provide over 80 percent of our total energy, humanity wouldn’t die. However, the world would look very different.” On this point, environmentalists would probably agree with him.

- International Energy Agency, Coal-Fired Power: Tracking Report, November 2021, accessed online on 24.08.22.

- Anecdote from: Javier Blas, ESG Is So, So, So Yesterday: Elements by Javier Blas, Bloomberg Opinion, 05.08.22, accessed online on 11.08.22.

- Michaël Correia, «Criminels Climatiques», Ed. La Découverte, 2022, Seiten 100-101.

- Mickaël Correia, Criminels Climatiques [Climate Criminals], Ed. La Découverte, 2022, pages 100–101.

- Mickaël Correia, Criminels Climatiques [Climate Criminals], Ed. La Découverte, 2022, page 101.

- Charles Dickens, The Old Curiosity Shop, Chapman & Hall London, 1841.

- Charles Dickens, Bleak House, 1853, cited in La civilisation du charbon [The Civilisation of Coal], page 36.