Shopping & manipulation E-commerce "dark patterns" fuel fashion overconsumption

David Hachfeld und Jean Busché, 13. September 2022

Poverty wages, pressure, overuse of natural resources and mountains of garbage: the problems of mass fashion consumption are well known, and the nation's wardrobes are full. But why does fast fashion continue to flourish? One cause is advertising, which persuades consumers of needs and wishes, tempts us to make impulsive purchases, and awakens “hunting instincts” with supposed bargains.

With digitalization, the focus of marketing departments is primarily on online retail, because today around every third piece of clothing is bought online.

The Impact of "dark patterns"

Many online platforms design their interfaces to influence users’ actions by experimenting with various parameters such as site architecture, colours or phrasing. These types of interfaces, which aim to disorientate the user so that he or she performs or avoids a specific action, are called dark patterns. The aim is commercial: with dark patterns, online retailers influence user behaviour and entice consumers to make more and faster purchases and to disclose personal data.

The forms of these "dark patterns" are manifold: pop-up windows featuring discount codes with a very short term, extra advantages stating at a certain purchase value, and the unsolicited addition of articles or services in the shopping basket are just as much a part of the retailers’ bag of tricks as customer accounts that are difficult or impossible to cancel online and the unsolicited use of “cookies”, where ads for online shops follows us to other websites. Dark patterns are manipulative, but their use is often legal and exploits the lack of legislation and consumer protection in online shopping.

They influence our behaviour to encourage us to buy much more than we need.

Dark patterns are the lubricant in the engine of the online fast-fashion industry.

The Investigation

The Fédération romande des consommateurs (FRC) and Public Eye wanted to find out to what extent fashion consumers in Switzerland are exposed to “dark patterns”.

Together with a team of 17 volunteers, we systematically examined large online shops selling fashion for 20 of the most common tricks. Dark patterns were found on all 15 online shops examined, but the differences between the platforms are considerable.

More infos

-

Methodology

In a first step, 17 volunteer investigators analysed 15 webshops for 20 practices that could be identified as dark patterns. The volunteers were trained and then asked to go to their assigned sites, follow the same investigation scenario and complete an online form. In a second step, the authors investigated all the websites and cross-checked the results. Each site was surveyed between 4 to 6 times; each time by different researchers.

The survey was performed between May and July 2022 and covered the following sites: About You; Aliexpress; Allylikes; Amazon; Asos; Bonprix; Galaxus; Globus; H&M: La Redoute; Manor; Shein; Wish; Zalando; and Zara.

The sites were accessed from Switzerland in their mobile version.

The dark patterns included in the research are shown in the picture-gallery included in this article.

Summary of Results:

By far the most dark patterns, 18, were identified at the Chinese ultra-fast fashion shop Shein: the website dazzles visitors with so many ads and animated pop-up windows that users looking for something specific will find it hard to get past the various click traps.

The Chinese platform Aliexpress, the US company Amazon and the French Shop La Redoute follow some distance behind, but still with an above average number of different dark patterns. We found fewer dark patterns in the online shops of companies that still sell predominantly through brick-and-mortar stores, such as Zara, Globus and Manor. H&M uses slightly more tricks and ploys, with six dark patterns, taking the unenviable top spot in this group.

-

Particularly common are dark patterns which tempt consumers to buy more items, such as the display of supposedly exactly matching items as soon as something lands in the shopping cart (13 shops), or by calculating shipping costs if too little is bought (10 shops).

-

In order to bind consumers more strongly to them, 12 shops require or encourage customers to set up an account for an order, and 9 urge the consumer to subscribe to advertising newsletters.

-

We were also shocked by how difficult it is to delete such accounts and the associated personal data. While the setting up of an account is done in two or three simple steps, at 10 shops a cancellation is difficult or even impossible via the mobile website.

Also widespread is a classic among dark patterns: 9 websites make it difficult for users to refuse or adapt advertising "cookies". Five of the shops even exploit gaps in Switzerland’s comparatively lax data protection law and store cookies on visitors’ smartphones or computers without being asked.

More infos

-

Dark patterns, where do they come from?

The issue of dark patterns was first raised in 2010 by Harry Brignull, who describes himself as an “expert in deceptive digital practices”. Since then, it has become a matter of concern. Indeed, many platforms are now resorting to dark patterns, again contributing to the vulnerability of consumers in their online experience. In 2019 the first major study determined that out of 11,000 commercial sites analysed, 11% contained dark patterns. In 2020, similar research concluded that 95% of free apps in the Google Playstore used digital deception patterns.

The power of deceptive design

The problem? It works. Consumers are 2 to 4 times more likely to perform a specific action in an environment containing dark patterns.

To influence our choices, platforms modify the decision space or manipulate visible information. They can pull the user in a certain direction, for example by pre-selecting certain options such as the “choice” to accept a range of cookies or by forcing the user to create an account for a purchase or to access content.

Especially popular on E-commerce websites are elements “nudging” users in a certain direction with discounts or other special promotions. An additional tactic is to play on “Fomo”, the fear of missing out on something: as on the qoqa.ch site, which offers a decreasing percentage of items remaining, or on booking.com, which sends its customers alarmist messages about the few offers still available at a given price.

Dark patterns can also take the form of false directions through counter-intuitive colour coding or double negations. A common form is to influence by obstruction, as when signing up to a website or service is possible with one click but unsubscribing takes much more effort. The Norwegian Consumer Council has filed a complaint against Amazon accusing it of making the unsubscribe process particularly complicated.

It’s important to remember that dark patterns are not used by the shops according to feeling or discretion, but on the basis of studies and tests. Each of our online movements leaves a data trail, and this forms the gold of marketing analysts, where the effect of the smallest design or structural adjustment on a website can be evaluated immediately. Whatever increases sales, keeps consumers on a given page for longer, or provides more exploitable personalised data is implemented by marketing teams.

Gallery of the 20 Dark Patterns analysed

For this research, we analysed dark patterns, which are particularly common in the field of online shopping. The following picture gallery presents them with concrete examples.

More infos

-

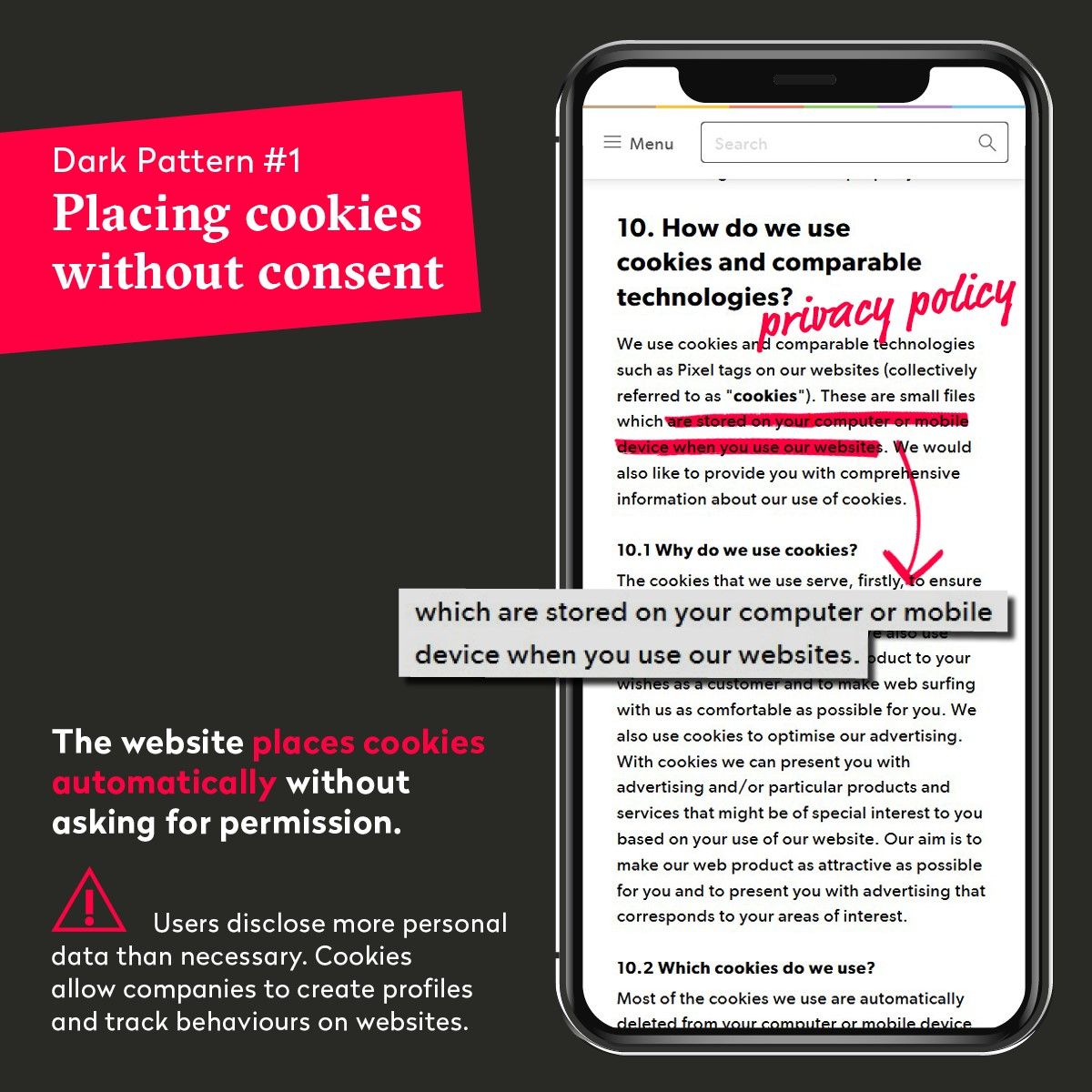

1: Placing cookies without consent

The website places cookies automatically without asking for permission.

Privacy! Users disclose more personal data than necessary. Cookies allow companies to create profiles and track behaviours on websites.

-

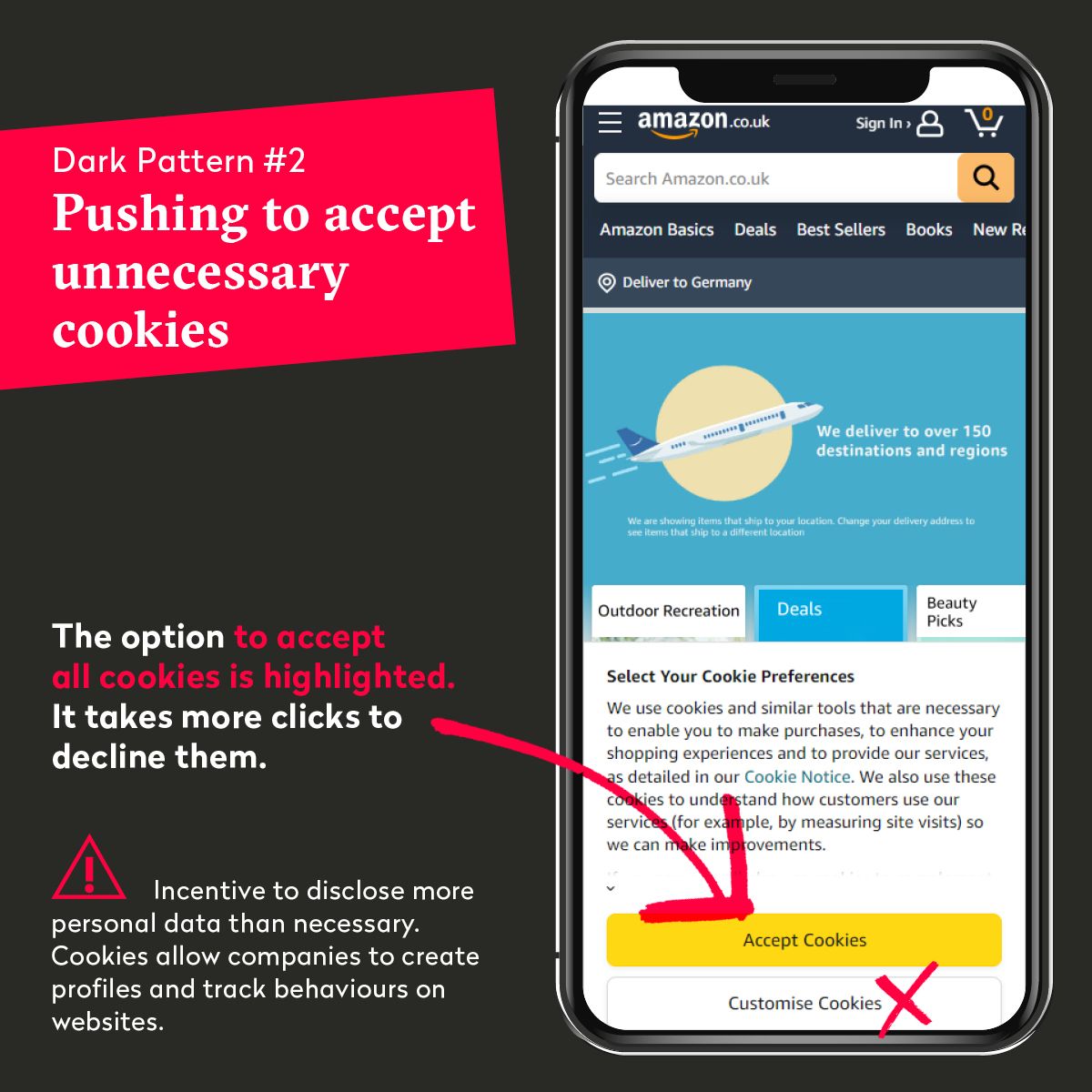

2: Pushing to accept unnecessary cookies

The option to accept all Cookies is highlighted. It takes more clicks to decline them.

Privacy! Incentive to disclose more personal data than necessary. Cookies allow companies to create profiles and track behaviours on websites.

-

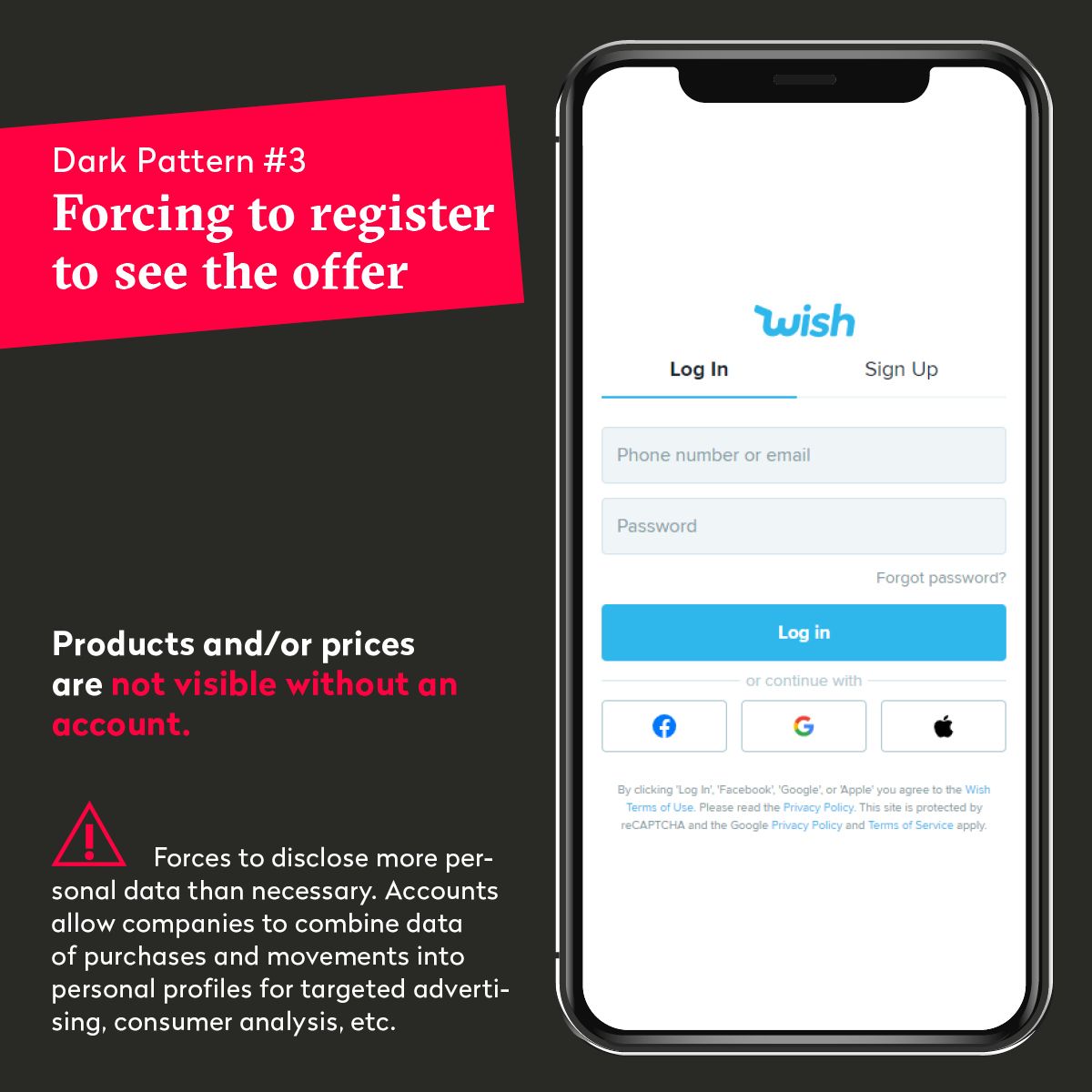

3: Forcing to register to see the offer

Products and/or prices are not visible without an account.

Privacy! Forces to disclose more personal data than necessary. Accounts allow companies to combine data of purchases and movements into personal profiles for targeted advertising, consumer analysis etc.

-

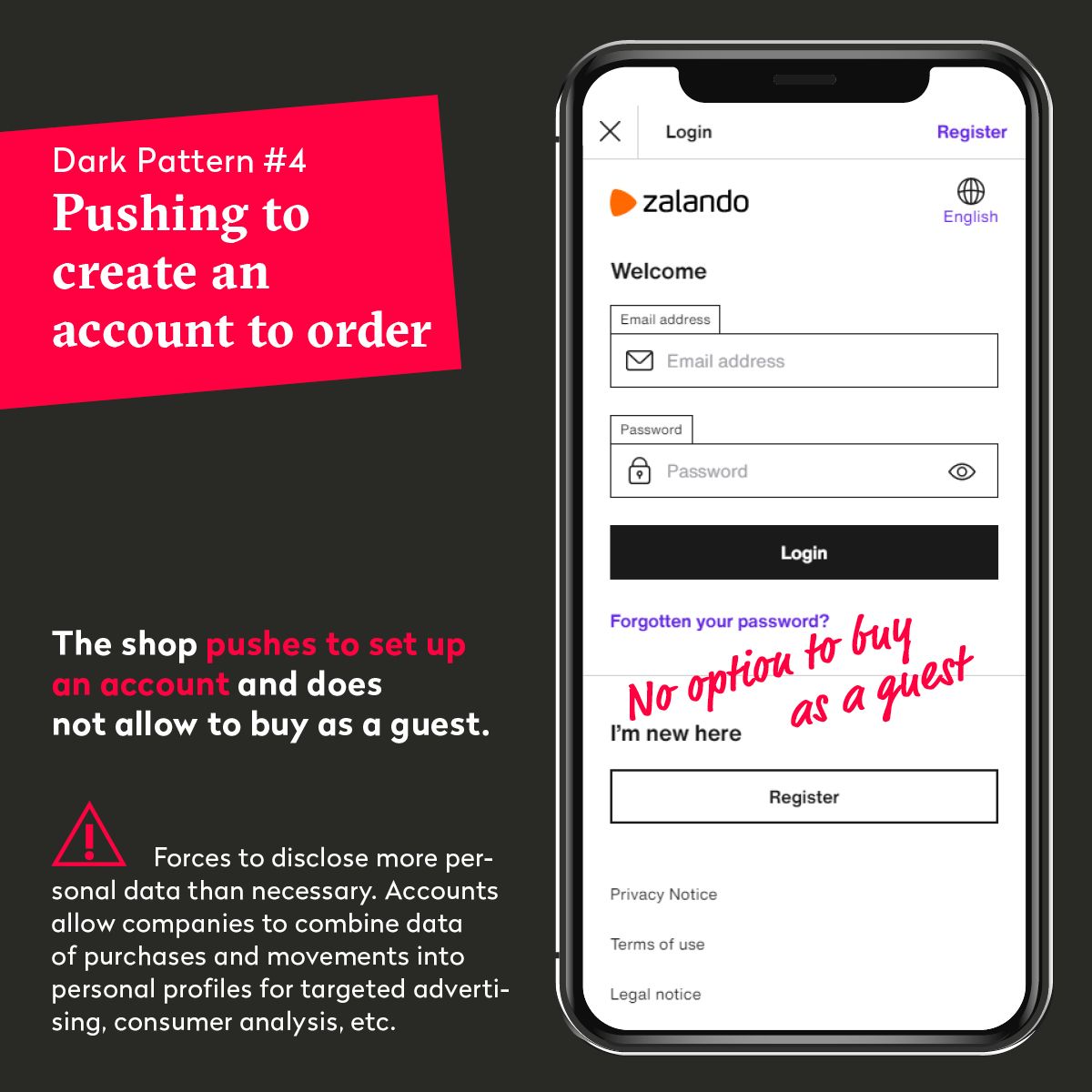

4: Pushing to create an account to order

The shop pushes to set up an account and does not allow to buy as guest.

Privacy! Forces to disclose more personal data than necessary. Accounts allow companies to combine data of purchases and movements into personal profiles for targeted advertising, consumer analysis etc.

-

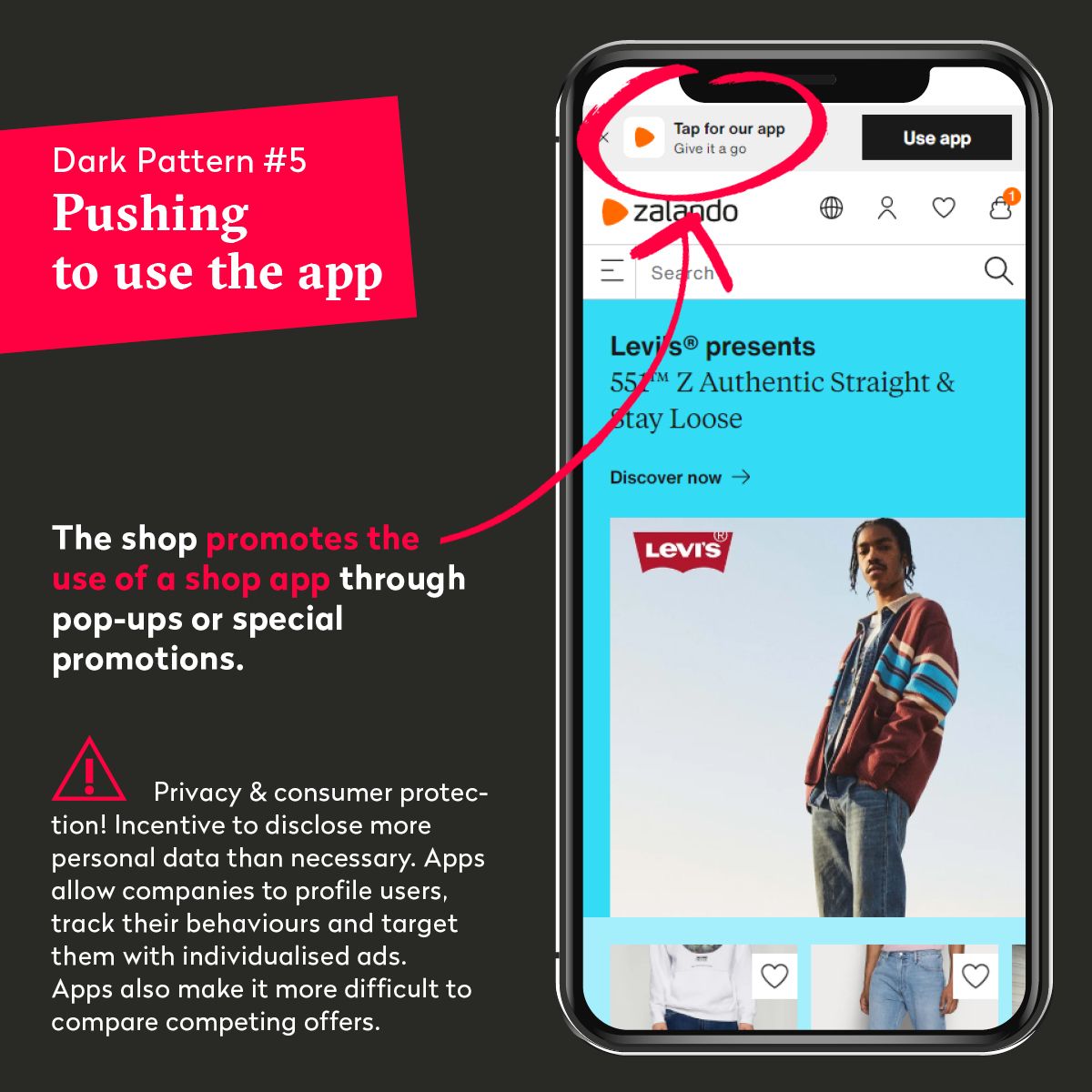

5: Pushing to use the app

The shop promotes the use of a shop app through pop-ups or special promotions.

Privacy & consumer protection! Incentive to disclose more personal data than necessary. Apps allow companies to profile users, track their behaviours and target them with individualised ads. Apps also make it more difficult to compare competing offers.

-

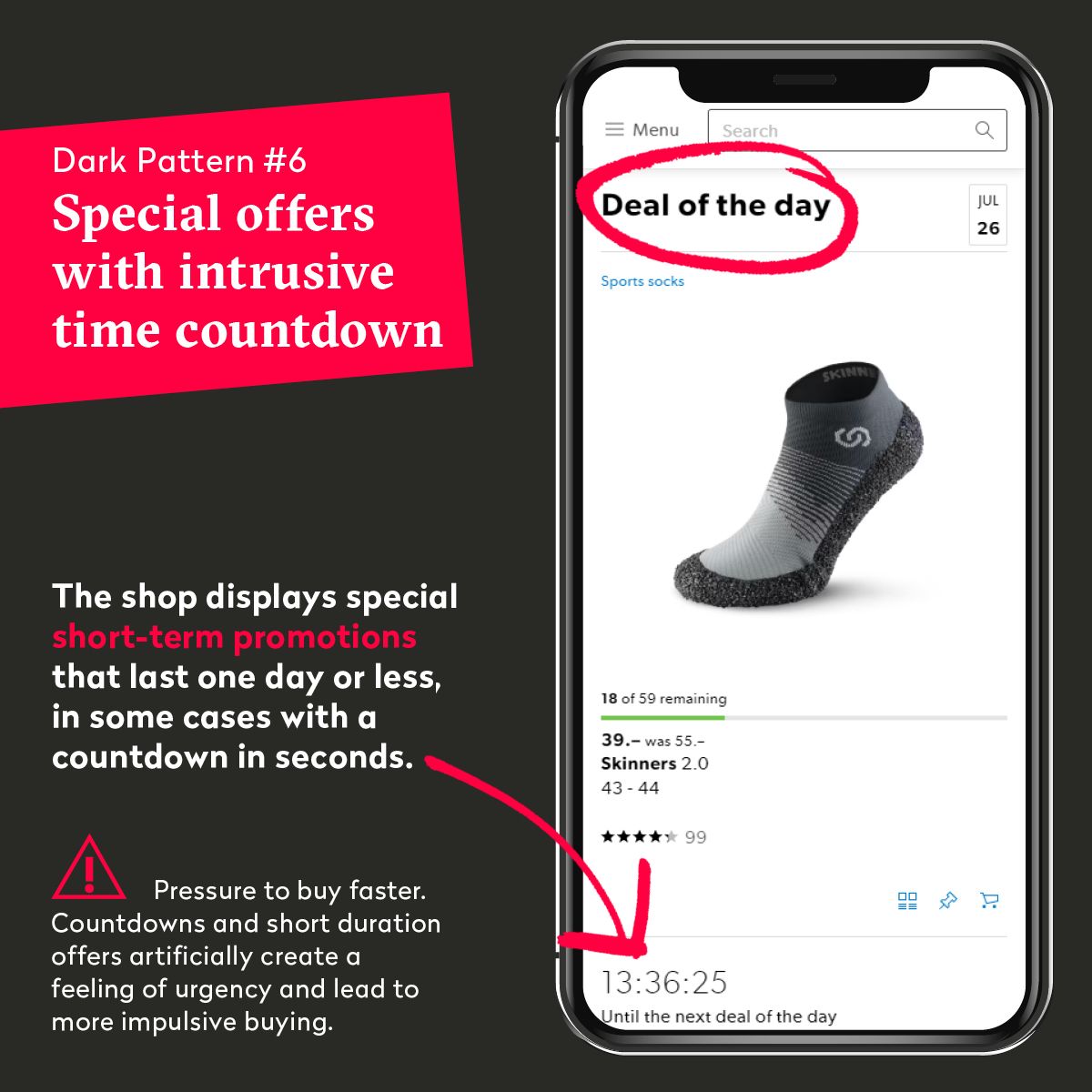

6: Special offers with intrusive time countdown

The shop displays special short-term promotions that last one day or less, in some cases with a countdown in seconds.

Pressure to buy faster. Countdowns and short duration offers artificially create a feeling of urgency and lead to more impulsive buying.

-

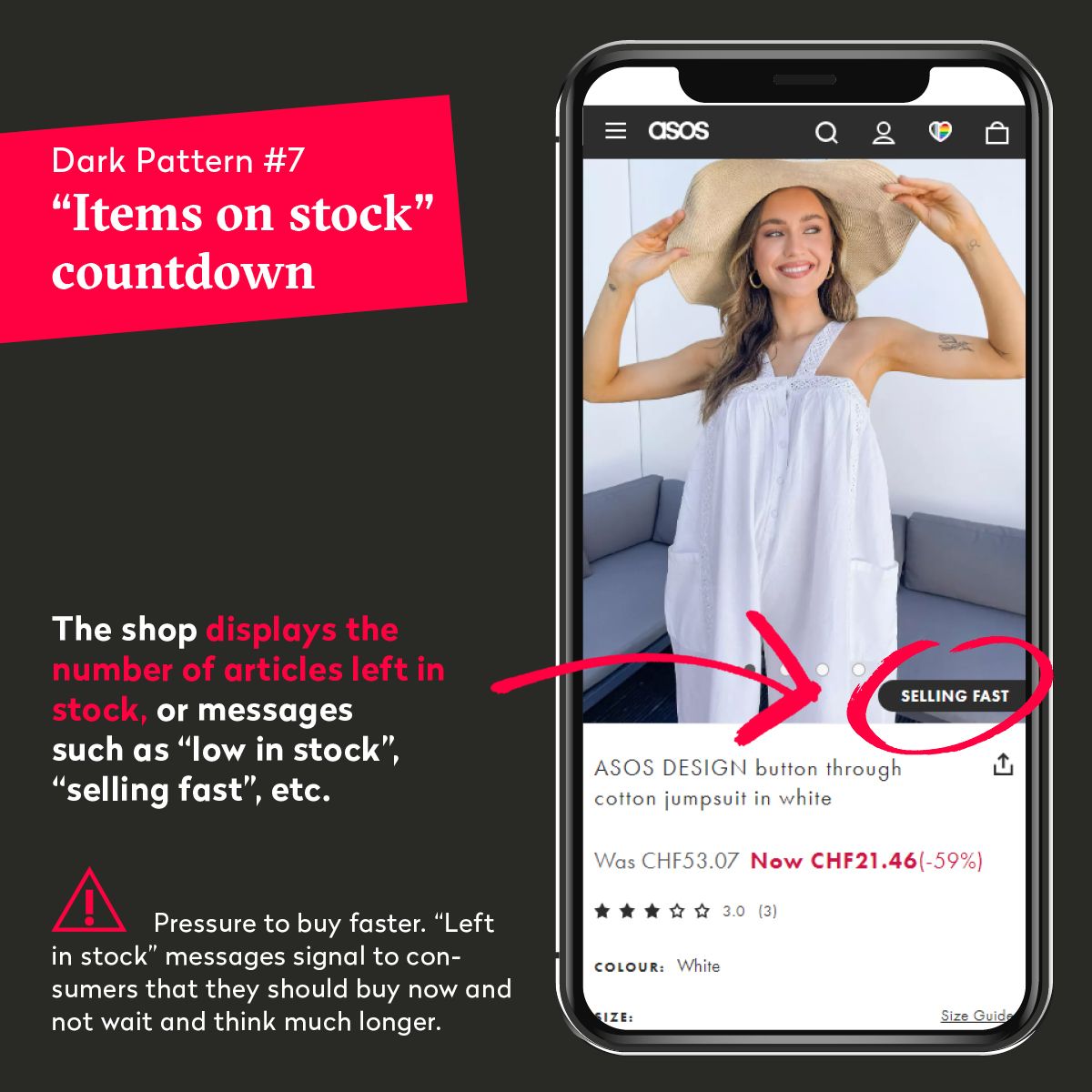

7: "Items on stock" countdown

The shop displays the number of articles left in stock, or messages such as "low in stock", "selling fast" etc.

Pressure to buy faster. “Left in stock” messages signal to consumers that they should buy now and not wait and think much longer.

-

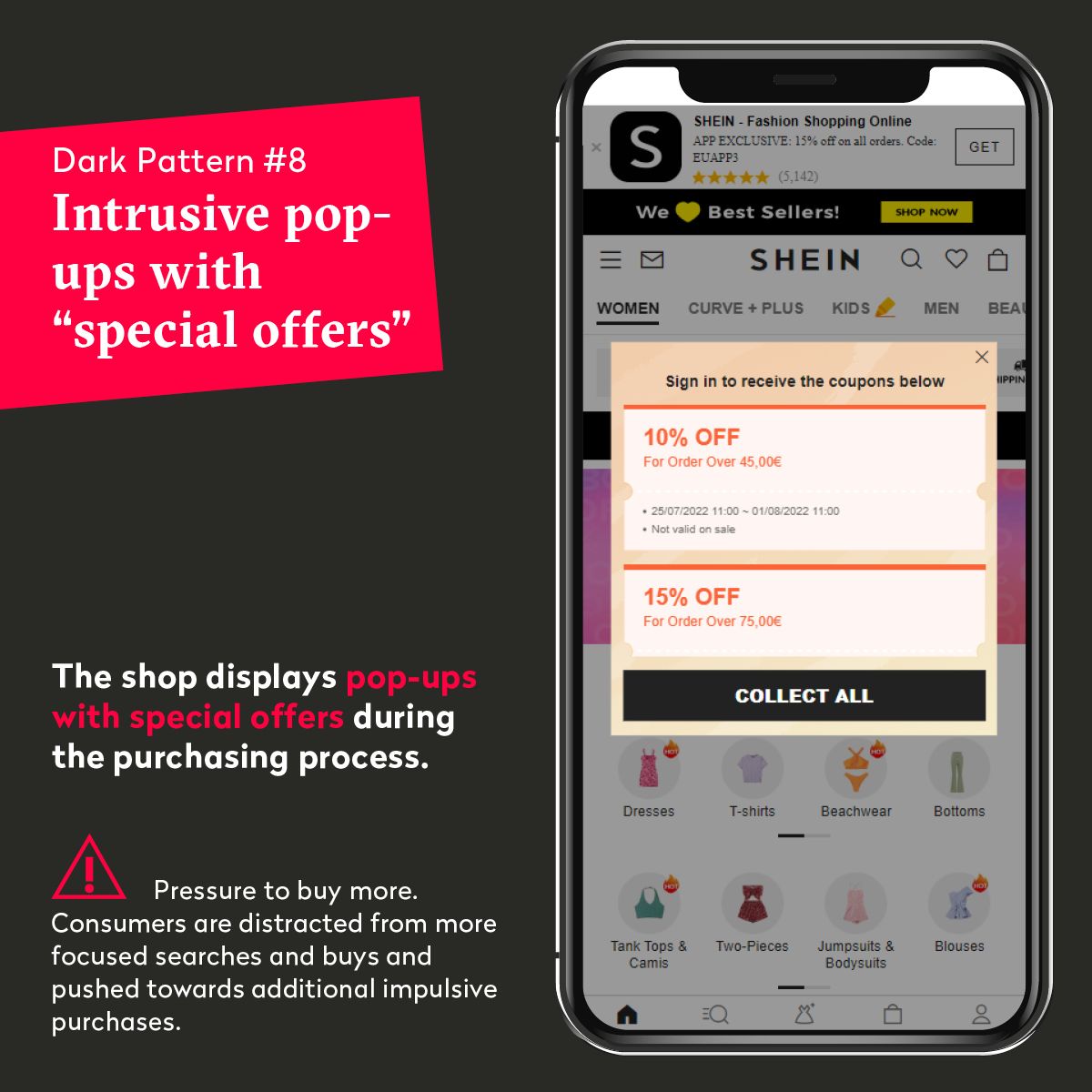

8: Intrusive pop-ups with "special offers"

The shop displays pop-ups with special offers during the purchasing process.

Pressure to buy more. Consumers are distracted from more focused searches and buys and pushed towards additional impulsive purchases.

-

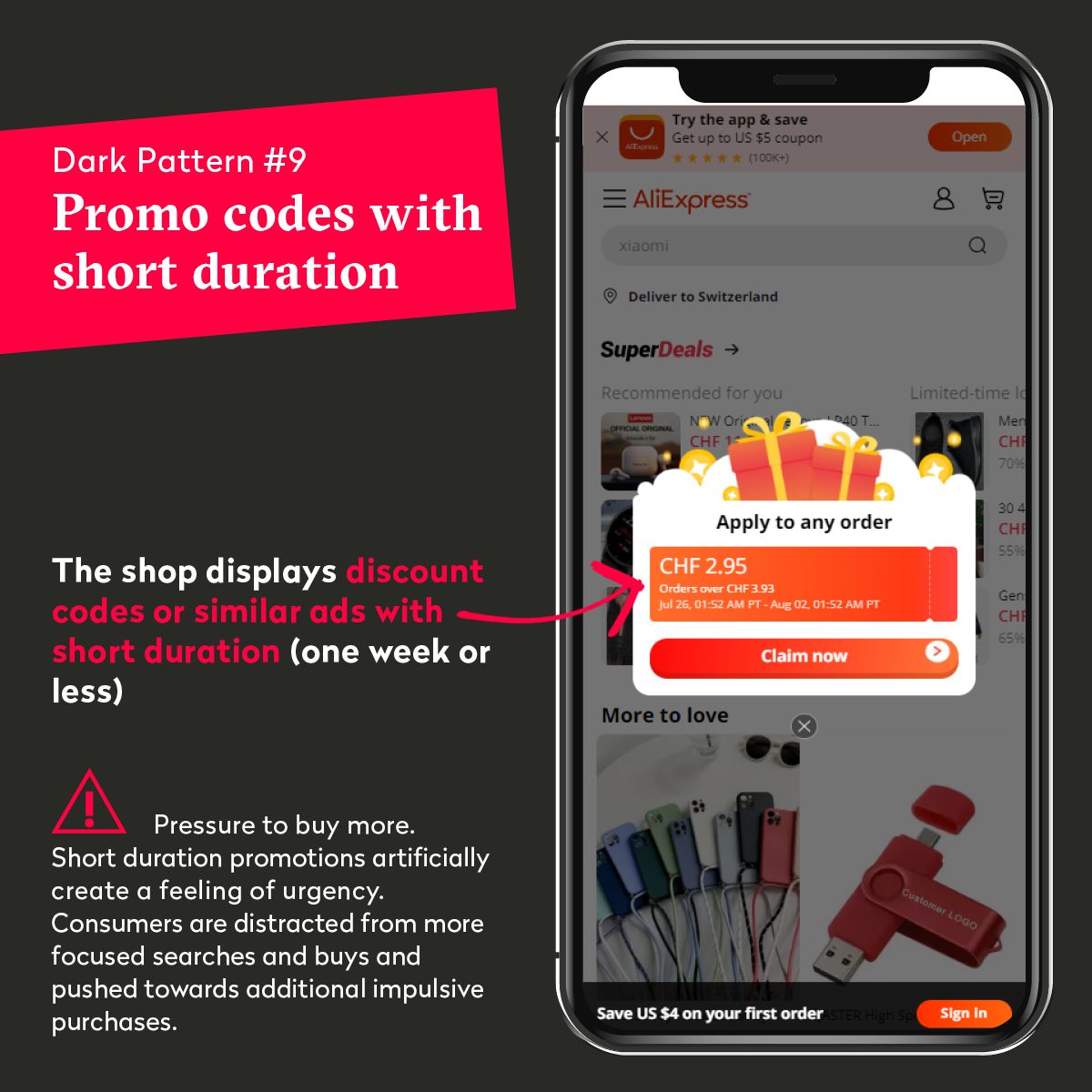

9: Promo codes with short duration

The shop displays discount codes or similar ads with short duration (one week or less).

Pressure to buy more. Short duration promotions artificially create a feeling of urgency. Consumers are distracted from more focused searches and buys and pushed towards additional impulsive purchases.

-

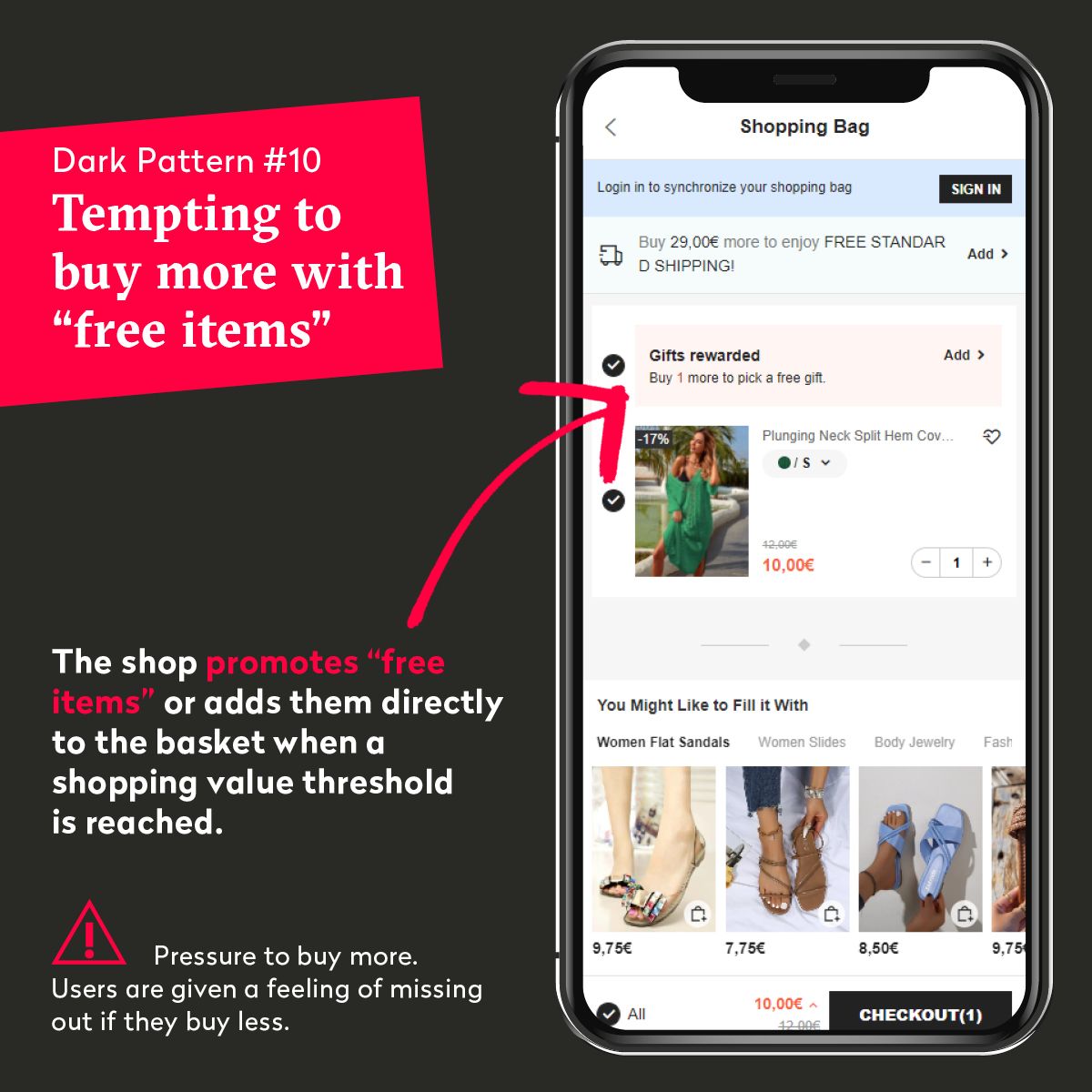

10: Tempting to buy more with "free items"

The shop promotes “free items” or adds them directly to the basket when a shopping value threshold is reached.

Pressure to buy more. Users are given a feeling of missing out if they buy less.

-

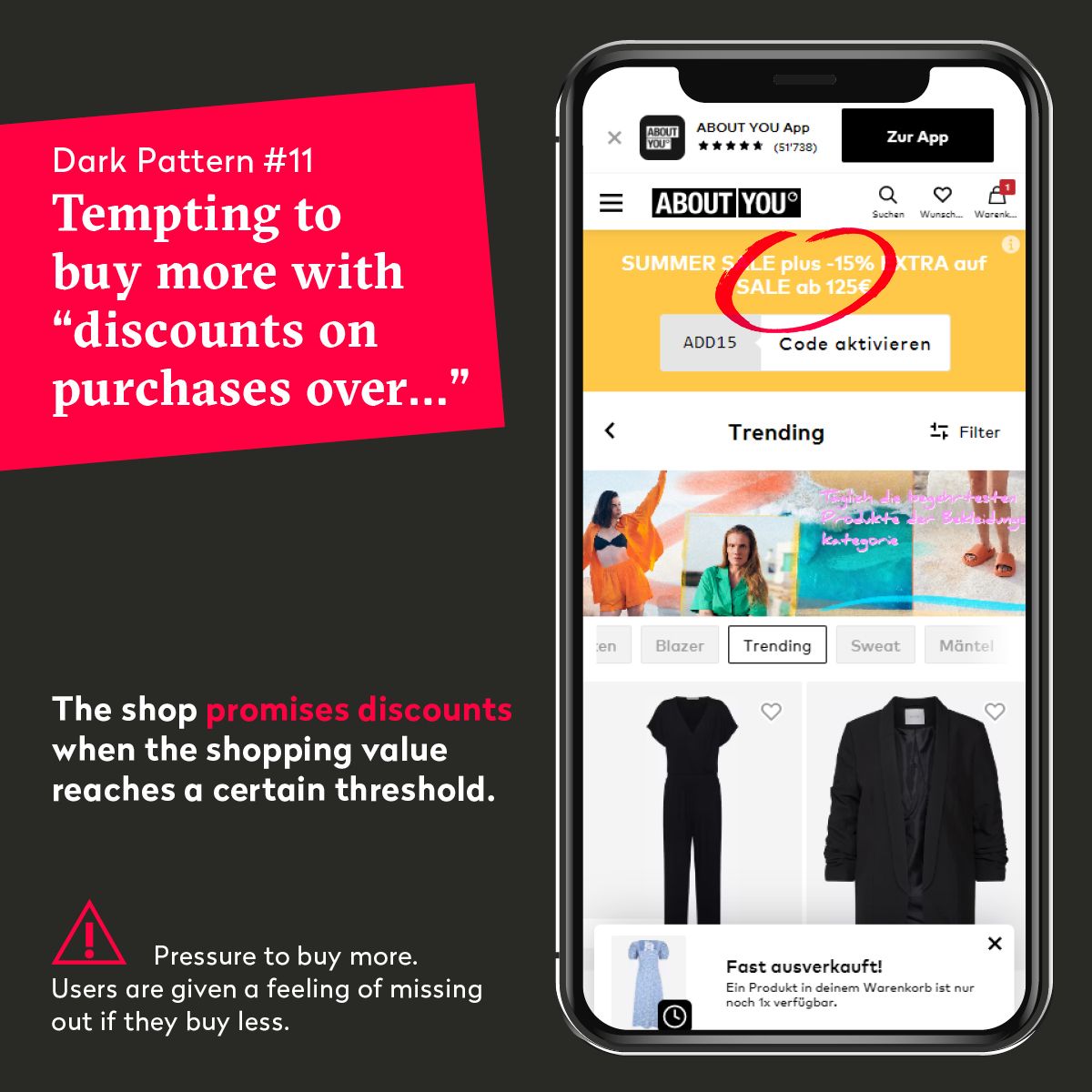

11: Tempting to buy more with "discounts on purchases over…"

The shop promises discounts when the shopping value reaches a certain threshold.

Pressure to buy more. Users are given a feeling of missing out if they buy less.

-

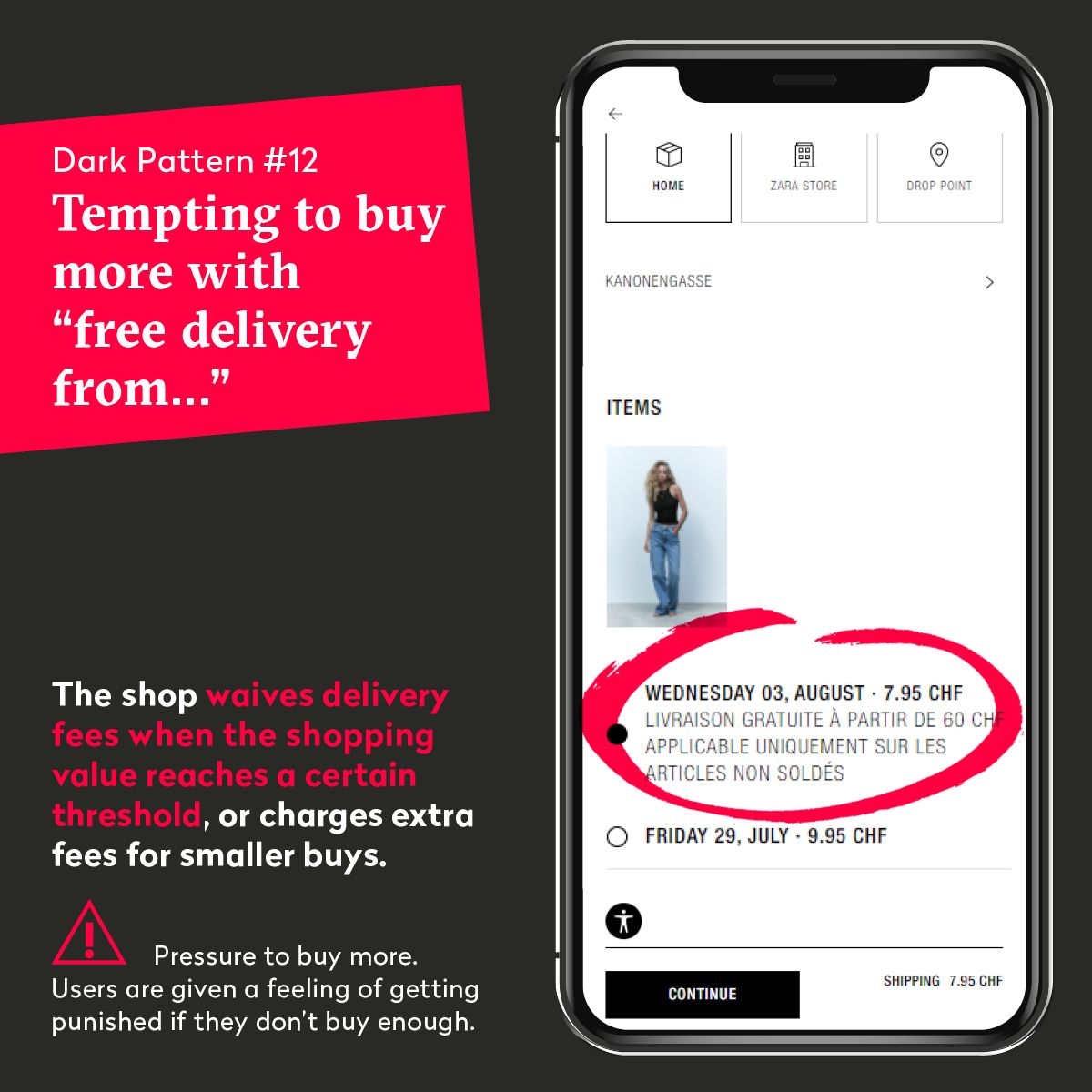

12: Tempting to buy more with "free delivery from..."

The shop waives delivery fees when the shopping value reaches a certain threshold, or charges extra fees for smaller buys.

Pressure to buy more. Users are given a feeling of getting punished if they don’t buy enough.

-

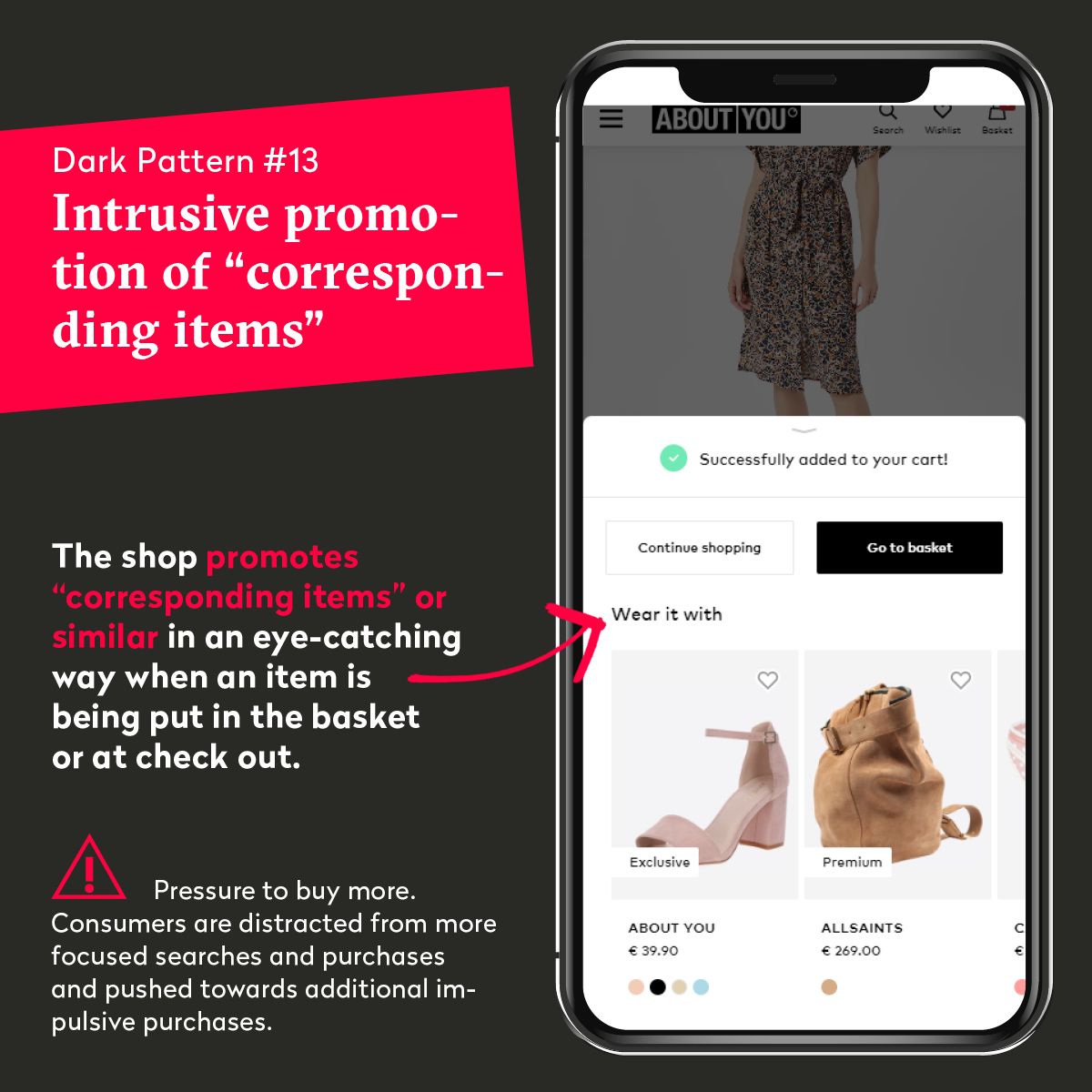

13: Intrusive promotion of "corresponding items"

The shop promotes “corresponding items” or similar in an eye-catching way when an item is being put in the basket or at check out.

Pressure to buy more. Consumers are distracted from more focused searches and purchases and pushed towards additional impulsive purchases.

-

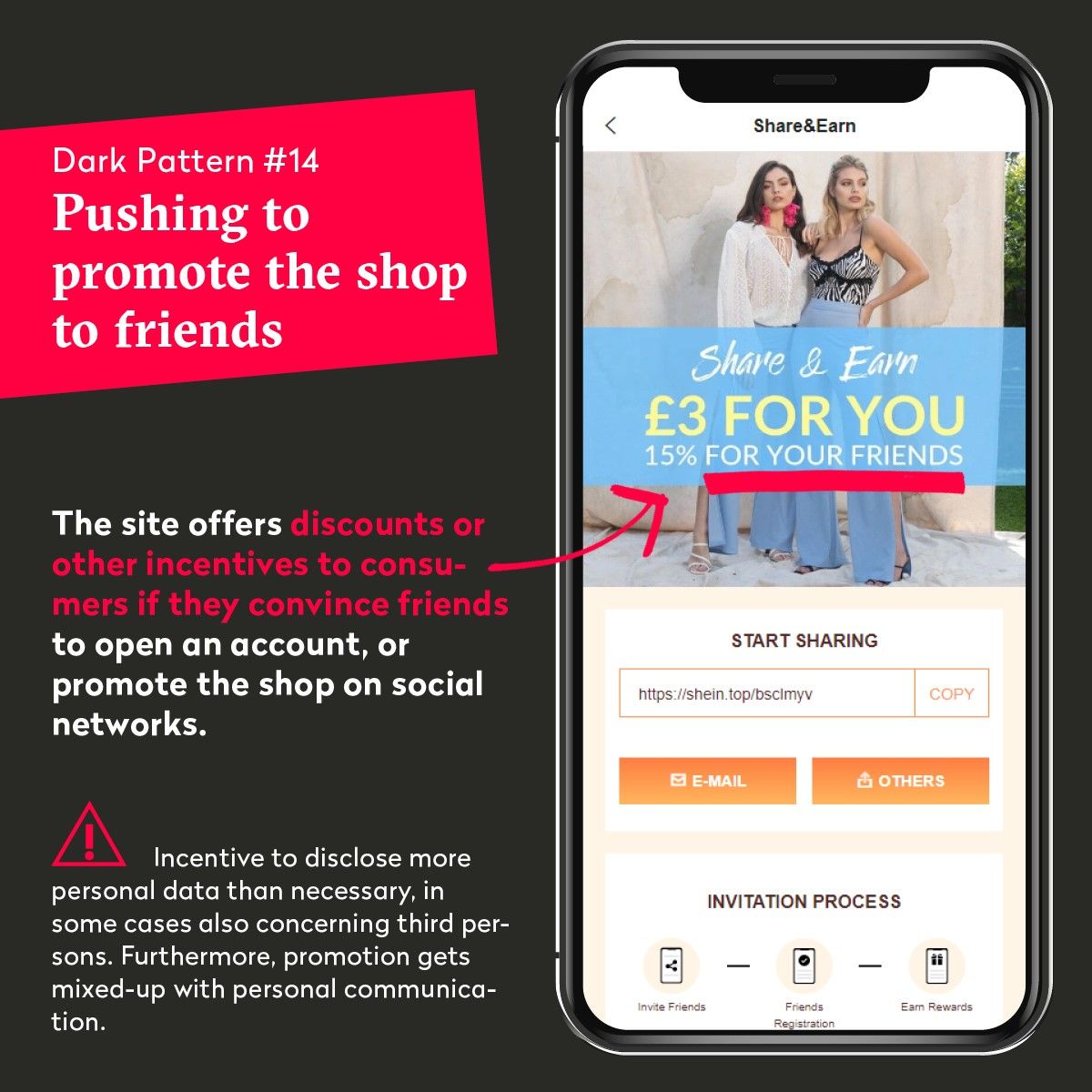

14: Pushing to promote the shop to friends

The site offers discounts or other incentives to consumers if they convince friends to open an account, or promote the shop on social networks.

Privacy! Incentive to disclose more personal data than necessary, in some cases also concerning third persons. Furthermore, promotion gets mixed-up with personal communication.

-

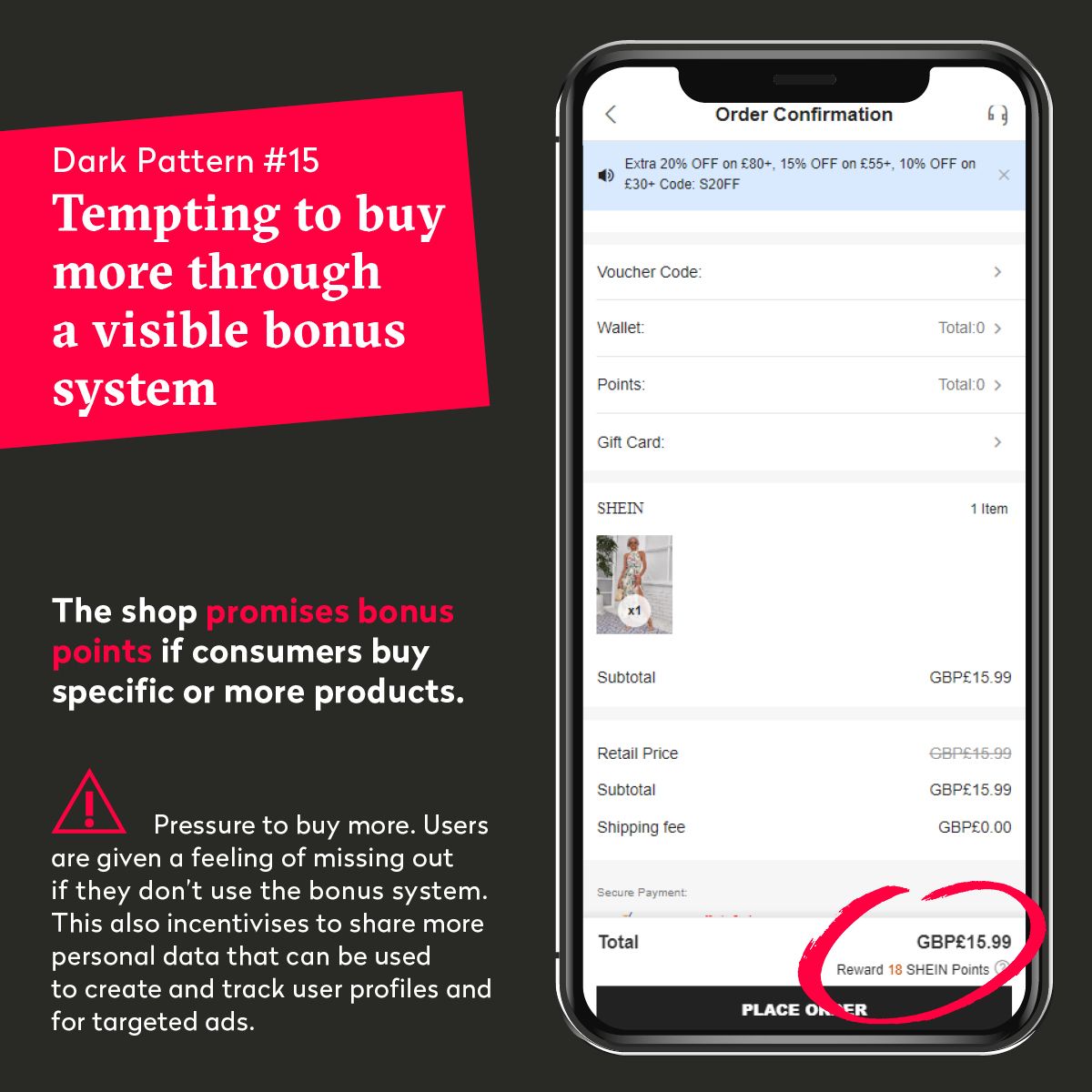

15: Tempting to buy more through a visible bonus system

The shop promises bonus points if consumers buy specific or more products.

Pressure to buy more. Users are given a feeling of missing out if they don’t use the bonus system. This also incentivises to share more personal data that can be used to create and track user profiles and for targeted ads.

-

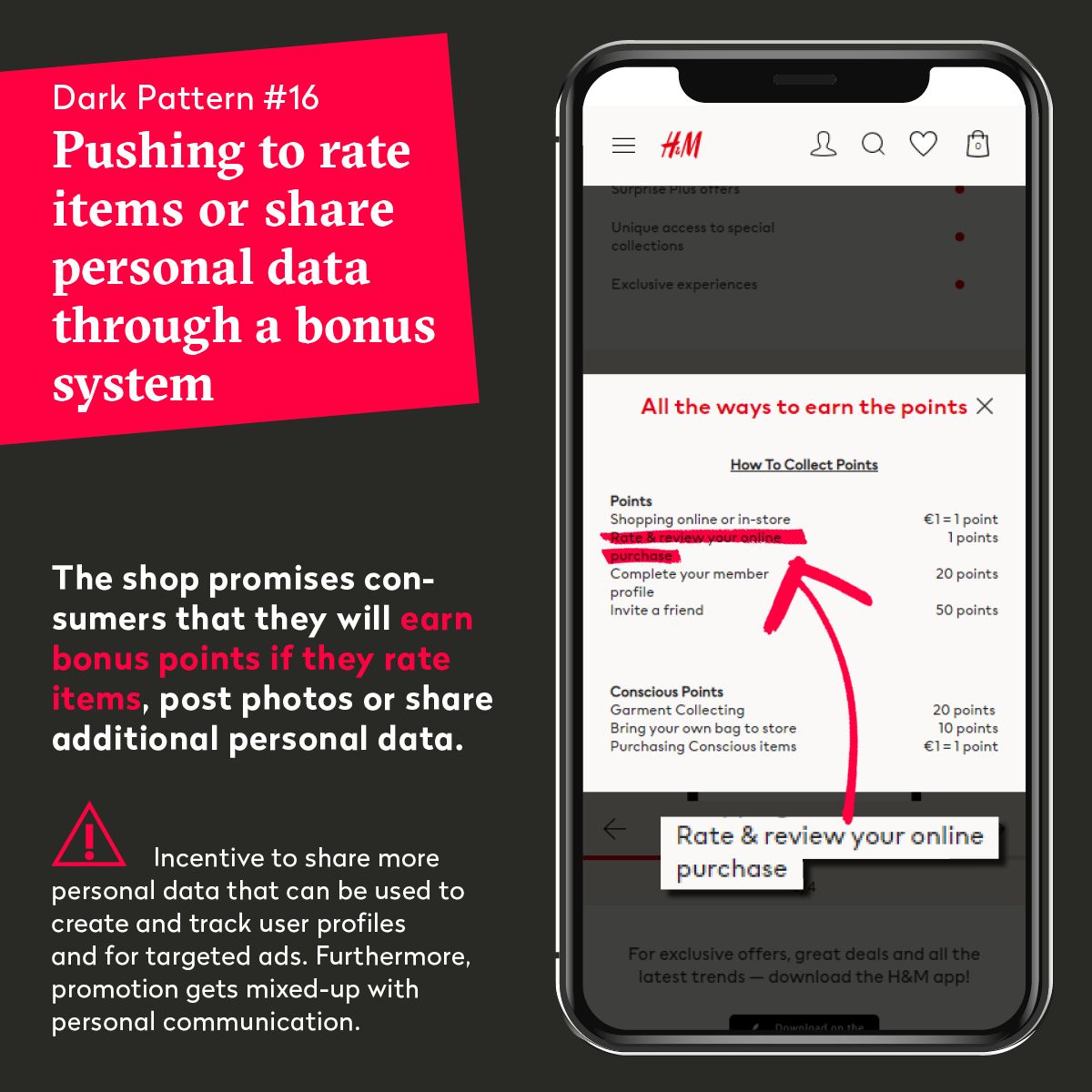

16: Pushing to rate items or share personal data through a bonus system

The shop promises consumers that they will earn bonus points if they rate items, post photos or share additional personal data.

Privacy! Incentive to share more personal data that can be used to create and track user profiles and for targeted ads. Furthermore, promotion gets mixed-up with personal communication.

-

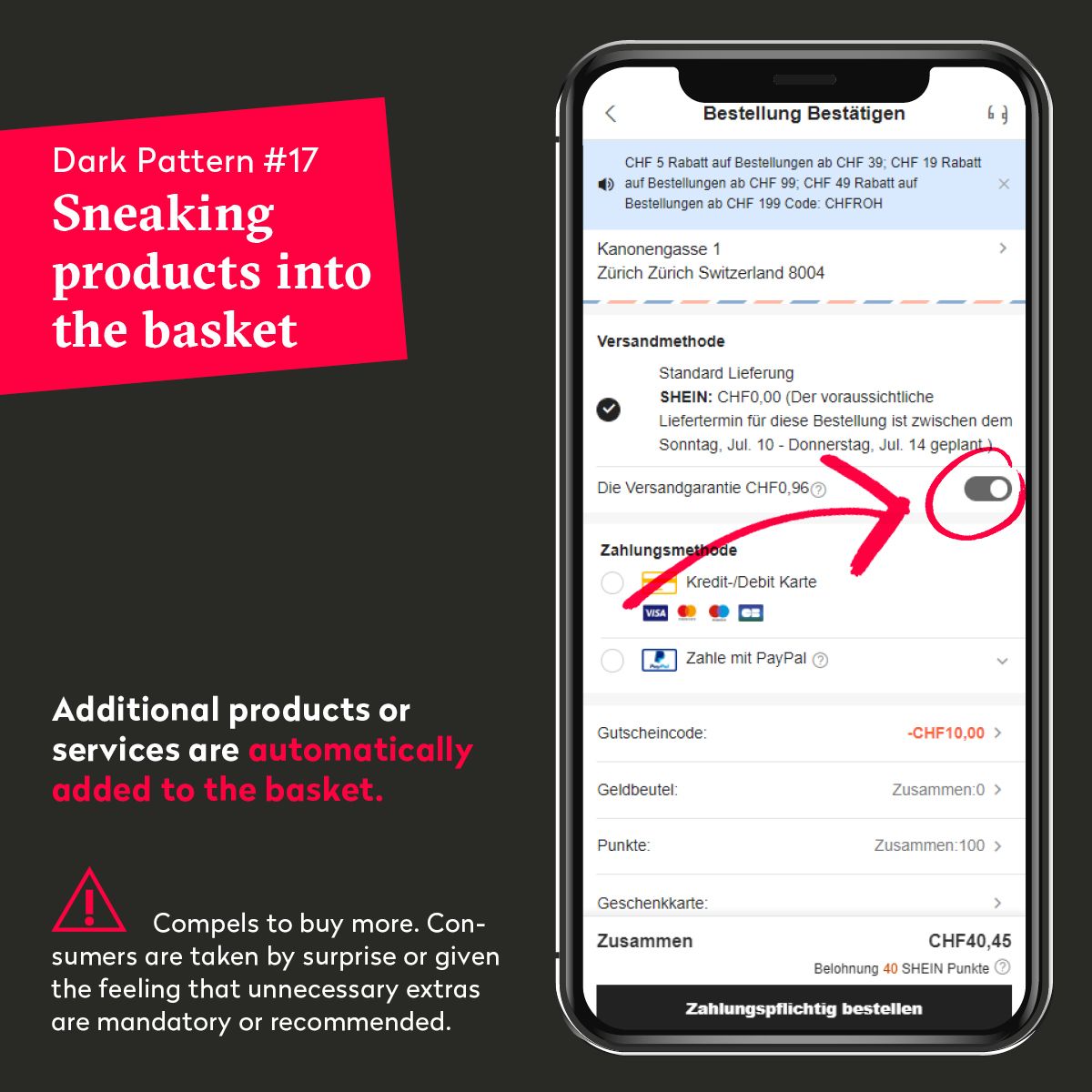

17: Sneaking products into the basket

Additional products or services are automatically added to the basket.

Compels to buy more. Consumers are taken by surprise or given the feeling that unnecessary extras are mandatory or recommended.

-

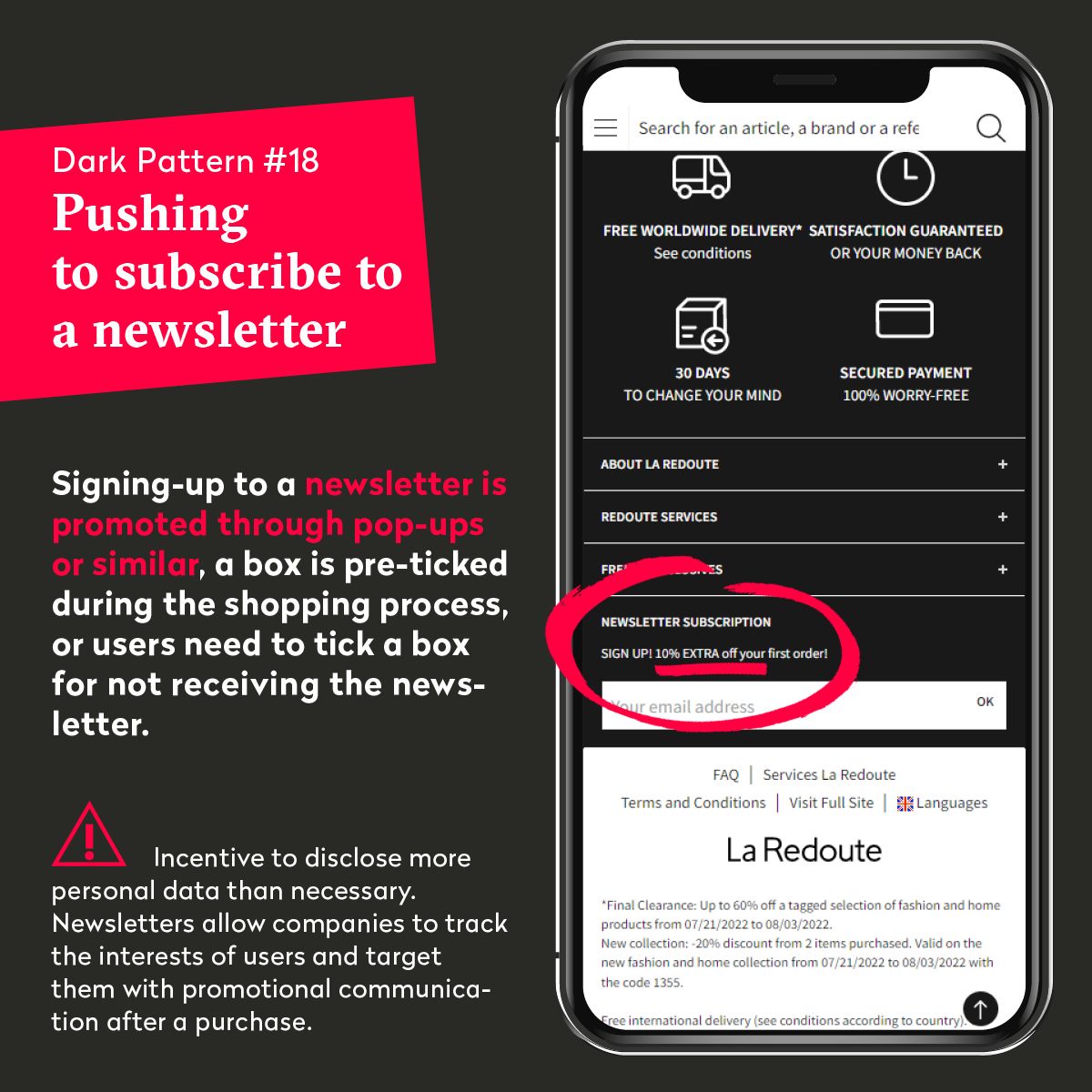

18: Pushing to subscribe to a newsletter

Signing-up to a newsletter is promoted through pop-ups or similar, a box is pre-ticked during the shopping process, or users need to tick a box for not receiving the newsletter.

Privacy! Incentive to disclose more personal data than necessary. Newsletters allow companies to track the interests of users and target them with promotional communication after a purchase.

-

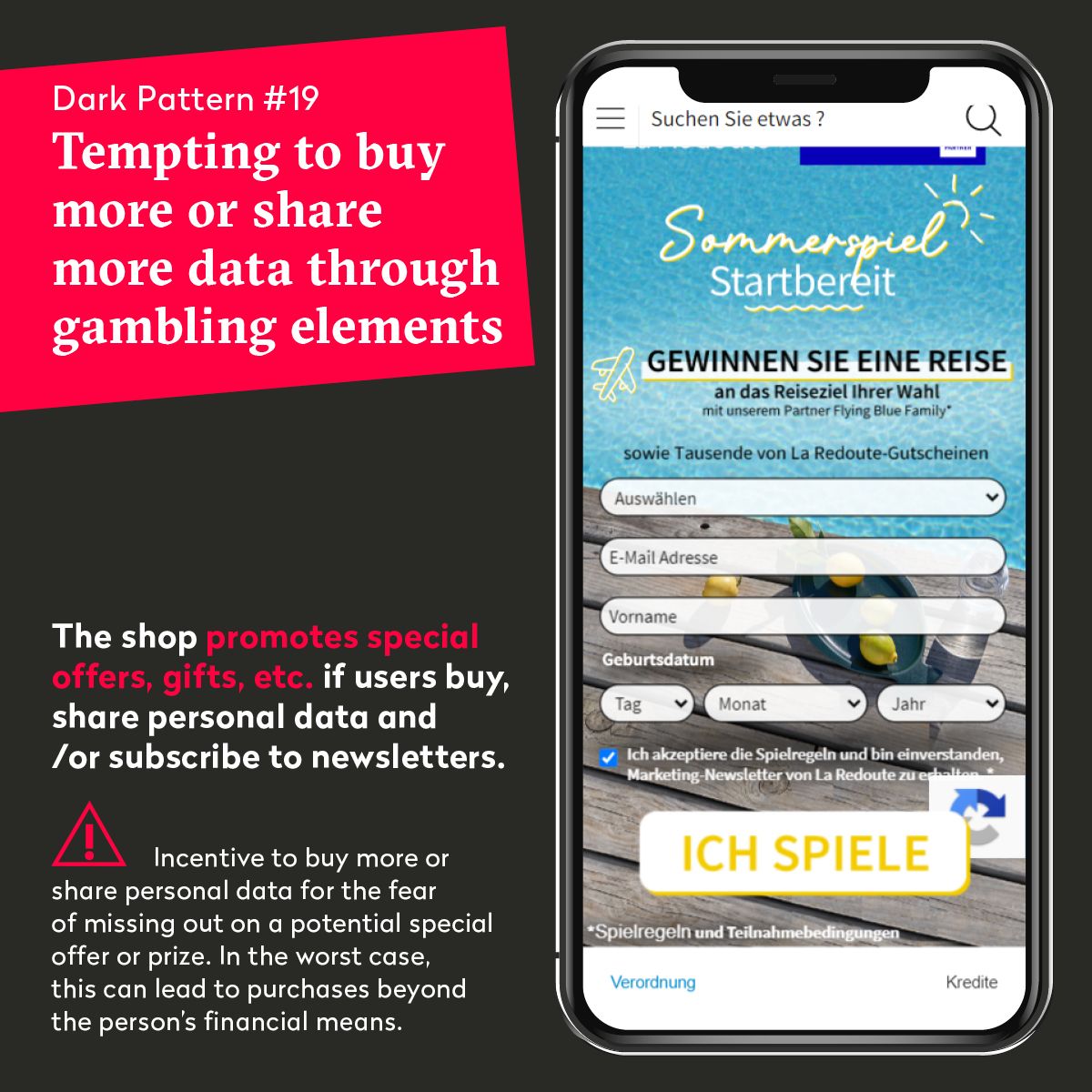

19: Tempting to buy more or share more data through gambling elements

The shop promotes special offers, gifts etc. if users buy, share personal data and/or subscribe to newsletters.

Privacy! Incentive to buy more or share personal data for the fear of missing out on a potential special offer or prize. In the worst case, this can lead to purchases beyond the person’s financial means.

-

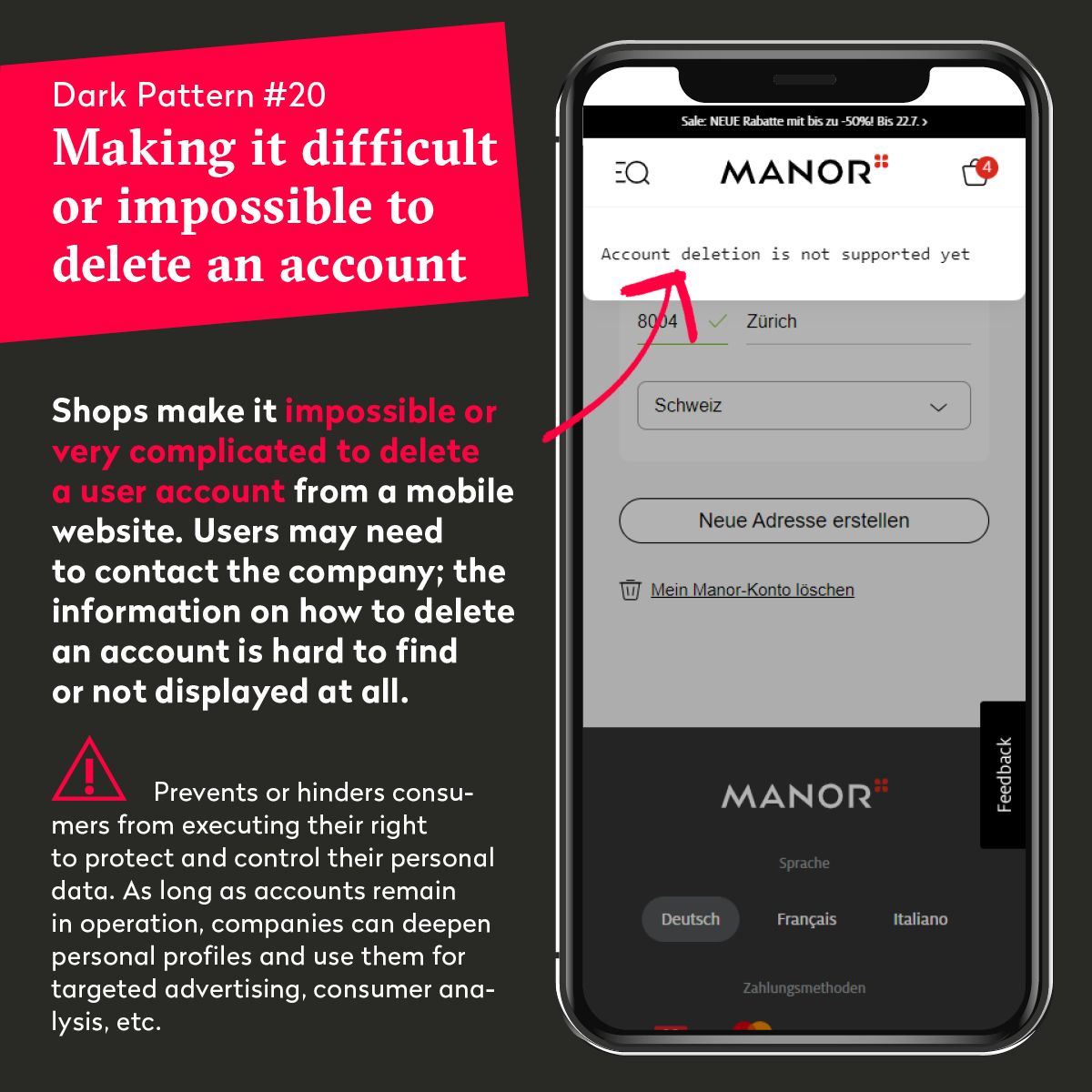

20: Making it difficult or impossible to delete an account

Shops make it impossible or very complicated to delete a user account from a mobile website. Users may need to contact the company; the information on how to delete an account is hard to find or not displayed at all.

Privacy! Prevents or hinders consumers from executing their right to protect and control their personal data. As long as accounts remain in operation, companies can deepen personal profiles and use them for targeted advertising, consumer analysis etc.

Slowing down fast fashion and protecting consumers

If you buy fashion online, you can't avoid dark patterns. Every shop examined uses at least some instruments from the bag of tricks of online marketing, and many play the whole keyboard: if it works and if it’s legal, or at least tolerated, it will be used.

Raising awareness of consumers about dark patterns and their impact can help us learn to avoid some traps, to be more careful with our data and to consume in a more self-directed way. But it would be wrong to consider dark patterns and the over-consumption they increase as purely an individual problem. Consumption beyond planetary boundaries is a systemic problem that we should also address with systemic solutions, through political regulation.

“Promoting more sustainable consumption patterns” is one of the guidelines set by the Federal Council in its Strategy for Sustainable Development. In its detail, the strategy has provoked a lot of criticism, as the Federal Council unilaterally focuses on individual behaviour change and refuses to take regulatory measures. In doing so, it ignores how much a lack of regulation undermines individualist approaches. Dark patterns undermine all efforts to promote a more sustainable way of consumption. They use the findings of consumer psychology to do exactly the opposite.

Politicians should decisively oppose this sabotage: to protect consumers, to promote a more sustainable way of consumption, and in order not to give competitive advantages to precisely those retailers who use manipulative instruments in a particularly unscrupulous way.

©

Bonprix

©

Bonprix

Political action is required

Dark patterns are omnipresent nowadays. The implications in terms of respect for individual choices, privacy protection and incitement to over-consumption are worrying. It is therefore time for the authorities and the legislator to take up these issues in order to regulate an industry that is cruelly lacking in standards.

Platforms should respect individual consumer choice by abandoning all forms of manipulation hidden within their interfaces.

At the same time we appeal to the authorities to enforce existing laws: sneaking unnecessary and unwanted items in the basket or mechanisms that make it excessively complicated, or impossible to terminate a subscription, raise issues of interference with the consumer's freedom of contract. Also, mechanisms for influencing user behaviour (colour, font size, or repeated dissuasive messages), raise questions of unfair competition when they are of significant intensity.

We therefore call for an outright ban on dark patterns that incite individuals to share more personal data or prevent them from deleting information about themselves: this goes against the idea of privacy by design and contributes significantly to the vulnerability of users.

Although the need for action is clear, the Federal Council is still reluctant to take up this issue. In the EU, in contrast, a first step, consisting of listing and analyzing problematic practices, has already been taken. Characterising these practices in the light of Swiss law is the second step, which will then make it possible to target possible means of action to protect the interests of Internet users and to force online platforms to respect users' choices.

The latest development in Bern is an encouraging sign that politicians are slowly waking up: the National Council, against the advice of the Federal Council, accepted a postulate (in French) instructing the administration to produce a report on the problem of dark patterns.