Consolidation: Fewer, large companies dominate global value chains

©

Paulo Fridman Corbis / GettyImages

©

Paulo Fridman Corbis / GettyImages

Global Value Chains

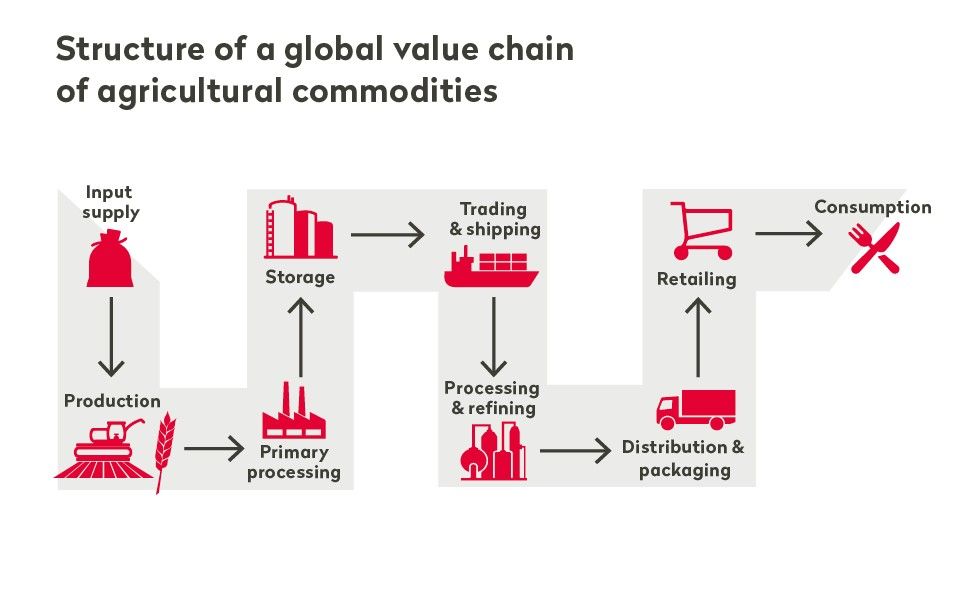

Generally defined, global value chains encompass all activities and processes needed to turn raw materials into final products that are delivered to end consumers. The spread of these activities and processes over several countries makes them global.

Consolidation in the agro-food sector is happening in the horizontal as well as the vertical dimension. Horizontal concentration means that individual stages of global value chains are increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few big companies. Vertical integration on the other hand, means that multinational companies gradually expand their activities and their influence across different stages of the value chain. This can be illustrated as seen in the figure below.

Horizontal concentration happens at all stages of global value chains, such as input, production, trading, processing, and retail (while the original functions are increasingly blurred). Mergers and acquisitions are the means of choice for agro-food companies in search of consolidating their power and influence over an ever-increasing part of global value chains. Other models of collaborations between powerful companies include joint ventures, strategic alliances, and contractual arrangements.

Over the last decade, mergers and acquisitions in the agro-food sector have increased both in terms of numbers and value. This process is far from over as witnessed by the most recent, announced, and planned mergers and acquisitions in the sector, which include a number of mega-mergers such as between Syngenta and ChemChina or Bayer and Monsanto.

In the midstream of agro-food value chains, where agricultural commodities are turned into foodstuffs, fodder, energy sources, and industrial products, concentration is well advanced. In cocoa processing for example there are just three companies (Barry Callebaut, Cargill, and Olam) which control around two thirds of the global market. Similarly in orange juice processing, Sucocitrico Cutrale, Citrosuco and Louis Dreyfus Company (LDC) control almost three quarters of the market. It is worth noting that all but one of these six firms operate from Switzerland.

©

Tim Boyle / Bloomberg Getty Images

©

Tim Boyle / Bloomberg Getty Images

The trading sector itself is no exception to these trends towards greater concentration. Indeed, the major agricultural commodity traders often operate in highly concentrated markets. For quite some time, the traditional trading houses of Archer Daniels Midland Company (ADM), Bunge, Cargill, and LDC, the so-called ABCD companies, dominated the grain trade. More recently, Asian traders such as COFCO International Ltd. (COFCO Int.), Olam International Limited (Olam), and Wilmar have joined the ABCD companies.

At the trading stage, mergers and acquisitions are driving the consolidation process as well. The precise extent of concentration is difficult to assess as trading companies are notoriously secretive. Estimates from different authors point to a limited group of firms who control large portions of the trade in individual commodities such as grains, coffee, tea, or bananas.

Vertical Integration

In the vertical dimension i.e., across different stages of the value chain, multinational companies have gradually expanded their activities and their influence beyond individual stages. With few exceptions, today’s large trading houses are highly vertically integrated companies who have expanded into the processing and production of agricultural commodities to compensate for dwindling trade margins.

Upstream, large-scale land acquisitions or long-term lease agreements (mainly in the case of plantation crops) as well as contract-farming arrangements have allowed traders to seize new business opportunities, reduce risks, and expand their influence in, and control of, the production stage. This is aptly illustrated by a quote from one of the leading coffee traders, Swiss-based Sucafina:

«If we were content to stay at this size and we weren’t vertically integrated, we would eventually get acquired by someone. (…) The trade house of the future will be more vertically integrated, and a big part of that’s going to have to come from the farming side».

This is confirmed by our 2021 report (available in German and French) on land acquisition control by the largest Swiss-based traders. Collectively, they control 2.7 million hectares of land. On well over 550 plantations, they produce mainly sugar cane, palm oil as well as grains and oilseeds.

The production stage is thus increasingly under pressure and traders are trying to secure whatever added value there is left, more often than not to the detriment of small-scale producers and workers. Moving upstream into agricultural production allows trading companies a more direct, reliable, and traceable access to the quantities and qualities they require to make full use of their storage and processing capacities, and to minimize risk.

©

Daniel Acker / Bloomberg GettyImages

©

Daniel Acker / Bloomberg GettyImages

Vertical integration is not only happening upstream, but also midstream at the level of processing and logistics. Some companies have impressive transport and storage capacities which they cannot fully utilise themselves and therefore they also do business with third parties. Others generate large parts of their turnover with processing and food production rather than with their traditional trading business.

The reach of a typical agricultural trading company can often stretch across entire global value chains.

The consequences of this unprecedented consolidation are fewer but more powerful firms as Public Eye documented in its publication Agropoly. These trends have exacerbated existing power imbalances in agro-food value chains, thereby making „farmers ever more reliant on a handful of suppliers and buyers, further squeezing their incomes and eroding their ability to choose what to grow, how to grow it, and for whom”, according to the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems.

Moreover, the increasing dominance of big companies in the agro-food sector allows these companies to expand their political influence to alter the rules that govern global value chains in their favour. University of Chicago economist Luigi Zingales warns that “market concentration can easily lead to a ‘Medici Vicious Circle’ where money is used to get political power and political power is used to make money.” The wide-ranging impacts of these consolidation processes often escape the scrutiny of regulators due to the narrow mandate of domestic competition authorities.