Intermediaries in corruption

©

Keystone / Gaetan Bally

©

Keystone / Gaetan Bally

Company and business structures play a central role in cases of corruption and money laundering by facilitating the concealment of actors’ identities – if the proceeds of corruption are placed in one or several companies, it is no longer possible to identify the owner of the assets. This makes it harder or impossible to investigate. Assets often flows through numerous – mostly weakly regulated – jurisdictions and exploiting the loopholes in the international fight against money laundering.

Switzerland – a haven for money laundering and corruption

Switzerland is home to one of the world’s leading financial centres. The industry contributes 9.7% of the country’s GDP, making it the largest economic sector. Switzerland is also leader in cross-border wealth management – a fact that has made Swiss bankers proud for over a century. In late 2019, over CHF 7893 billion was managed by the Swiss finance industry; half of this sum from abroad. This gives Switzerland approximately 25% of global market share.

Switzerland plays a significant role in many sensitive sectors, including commodities trading; the defence industry and the pharmaceutical industry. These sectors are vulnerable to corruption, because they are characterised by lack of transparency, weak regulation and the key role played by state actors. The commodities sector is particularly high risk. In a 2019 report on corruption as a predicate offense to money laundering, the federal government stated:

“Business activities associated with commodities trading pose a high risk of corruption due to the actors involved (state-owned entities, foreign officials), the significant potential to make profits, the lack of transparency around transactions (in particular purchases made by state-owned entities) and the lack of specific regulations or international standards for these transactions.”

Swiss banks and the proceeds of corruption

Landmark cases make it clear that illegal assets continue to flow through Swiss banks and that there are severe shortcomings with regard to the application of the Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA).

The Lava Jato corruption scandal demonstrates the far-reaching involvement of actors based in Switzerland, in particular of financial intermediaries. Since 2014, the Office of the General Attorney has been investigating cases related to the Brazilian parastatal oil company Petrobras and the construction company Odebrecht. Brazilian officials are accused of awarding contracts at inflated prices in return for commissions that were transferred to offshore accounts by intermediaries. In this case, the Brazilian authorities addressed over 100 requests for legal assistance to Bern. In 2017, the Swiss authorities had already investigated over 1,000 accounts with over 40 Swiss banks. According to their findings, the sums involved in the corresponding suspicious activity reports (SARs) totalled over CHF 1 billion. Despite the significant participation of Swiss banks in the affair, then federal president Doris Leuthard stated in 2017 that the Lava Jato scandal was “a Brazilian problem, not a Swiss one”.

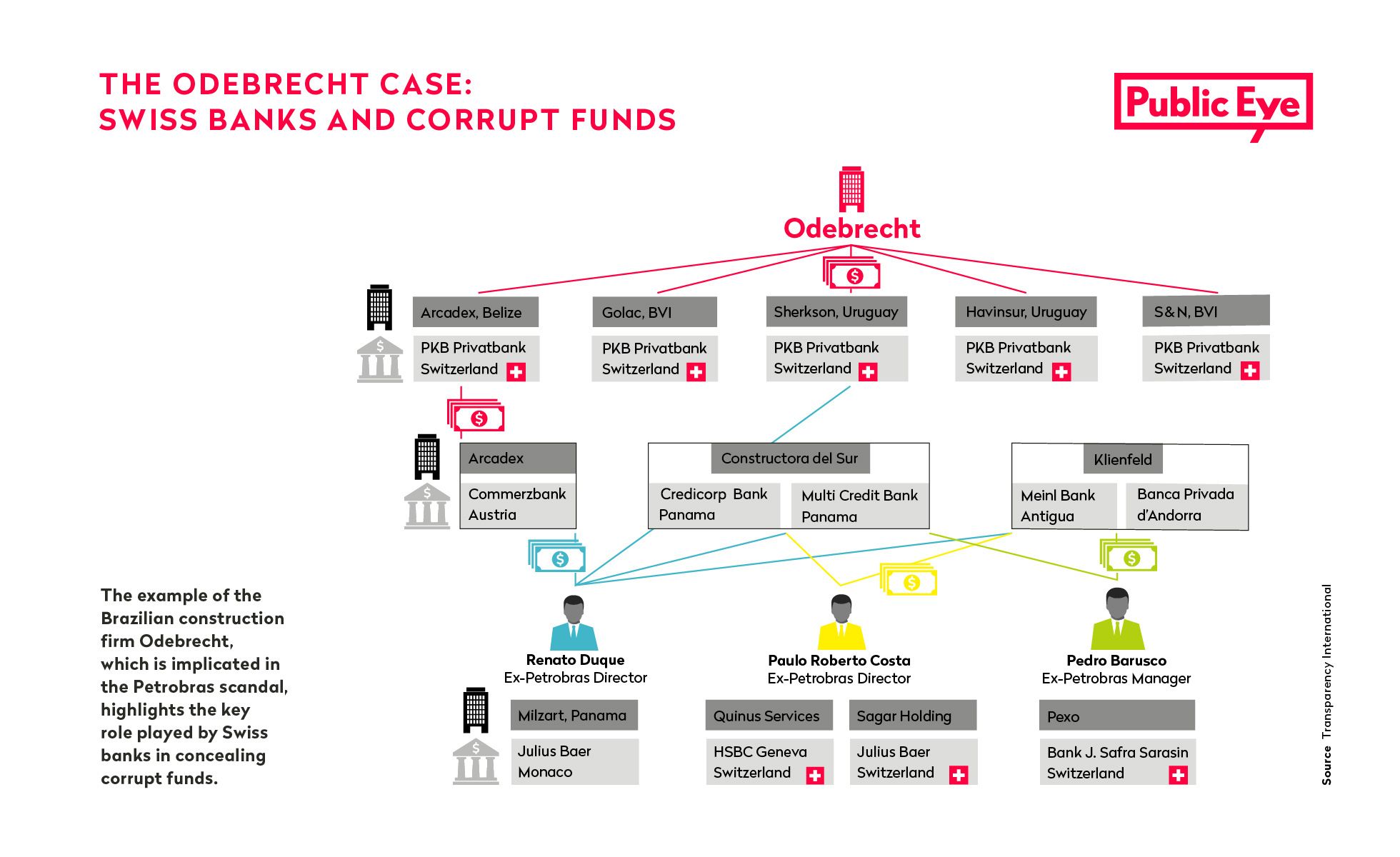

The role of the Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht in the Lava Jato scandal clearly demonstrates the importance of Swiss banks in this huge corruption affair. Odebrecht had collaborated with other construction companies to obtain the contracts with Petrobras. They formed a cartel and paid bribes to both politicians and the leadership of the Brazilian oil company. Odebrecht’s payments passed through a Swiss bank (PKB Privatbank) to other Swiss banks. Former Petrobras management had accounts with banks including HSBC Private Bank, Julius Bär and J. Safra Sarasin bank. Among those account holders was Paulo Roberto Costa, the former director at Petrobras who acted as one of the key ‘pillars’ of the corrupt network and who was convicted of money laundering and racketeering in relation to this case in Brazil in 2015.

The example of Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht, which is implicated in the Petrobras scandal, highlights the key role played by Swiss banks in concealing the proceeds of corruption.

Shortcomings in banks’ implementation of AMLA

The cases of Petrobras and Odebrecht illustrate the limitations of the oversight by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA). In Switzerland, the system is based on bank supervision and self-regulation. Banks and other financial intermediaries are required to combat economic crime. Yet it is up to banks alone to determine whether to maintain a business relationship. At the same time, a banks primary objective is to make profit. The friction between a bank’s legal duties and its drive to make profit is one of the main stumbling blocks in the Swiss supervisory system – the system requires financial intermediaries to assess their own customers and report suspicious activities themselves.

Statistics produced by the Money Laundering Reporting Office Switzerland (MROS) demonstrate that the surveillance carried out by banks is lacking.

Banks generally only report suspicious activity after it has been reported by the media. According to a report by the Interdepartmental Coordination Group to Combat Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (KGGT), over half of reports from 2008 to 2017 were made after media reports.

Swiss banks in the centre of Venezuela’s PDVSA scandal

In 2016, United States Attorney Preet Bharara subpoenaed documents on 18 financial institutions based in Switzerland in relation to embezzlement at state-owned oil company Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). A group of business people known as ‘Bolichicos’ used their connections with Hugo Chávez’s regime and became rich at the expense of the Venezuelan population, who are among the poorest in the world.

Since 2018, FINMA has been investigating numerous Swiss banks for suspicions of money laundering because they accepted funds connected to PDVSA. A Julius Bär banker has been arrested in the US.

In 2020, investigations run by the Zurich police and public prosecutor's office revealed the scale of the plundering by the Venezuelan government. The total of suspect funding was allegedly CHF 9 billion, spread across hundreds of accounts at around 30 Swiss banks.

The bank whose name is cited most frequently in the US court documents is CBH Compagnie Bancaire Helvétique, headquartered in Geneva. It is suspected of having laundered USD 4.5 billion within two years.