Geneva Offshore Journey to the heart of a city of shell companies

Adrià Budry Carbó and Robin Moret, 5. October 2021

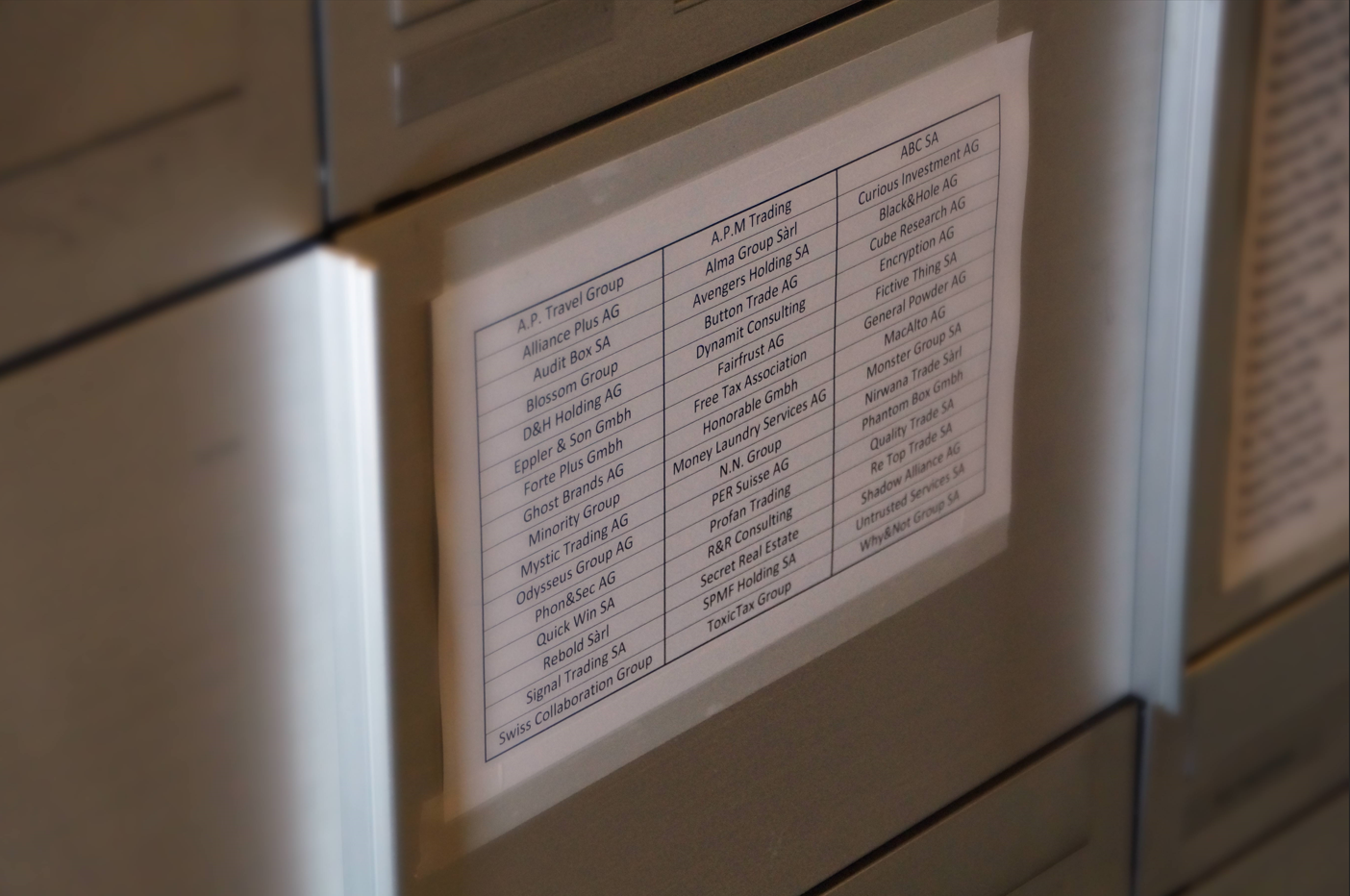

Geneva is not a great city for postal workers! As you go past the rows and rows of mailboxes, you will see company acronyms appear in their hordes and then disappear in an unobtrusively haphazard manner. Under the name of this law firm appears a list featuring dozens of names of obscure companies. The address of that fiduciary office is given for around a hundred structures, more or less, without any substantial presence. Most of them will be gone in a few months, leaving nothing but a few lines crossed out in a commercial register that’s continually changing.

This includes some of the “stars” of the offshore sector, who have disappeared due to “irreparable damage” inflicted on their reputation. “Mossack Fonseca, are you at home?” wondered the conscientious postman with concern in April 2016, leaving a note at Rue Micheli-du-Crest 4. With the hasty disclosure of the revelations by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), the founders of the law firm at the heart of the Panama Papers scandal had not informed Swiss Post of the closure of its Geneva office.

As was revealed five years ago, this was the residential building on an ordinary street from which more than 38,000 domiciliary companies had been created in Caribbean jurisdictions by some 1277 Swiss intermediaries. Crowd research conducted in June 2021, with the support of Public Eye volunteers, shows that two-thirds of the 211 individual administrators have flown the coop, but at least 120 of the 153 law firms criticised in the Panama Papers (78%) are still open for business. And of the 821 other Swiss fiduciary offices and financial intermediaries involved, three quarters are also still in business (73%). The rest of the intermediaries are composed of unidentified companies.

As revealed by the “Pandora Papers”, a massive data leak from 14 offshore firms made public by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), Swiss intermediaries continue to play a key role in setting up shell companies to conceal the origin of funds and their true owners. Of the approximately 20,000 offshore companies of the Panamanian law firm Alcogal, more than a third were linked to Swiss-based lawyers, fiduciaries or advisors. Their clients? Monarchs, despots of authoritarian countries or criminals.

The series of revelations therefore had no consequences at all: the domiciliary companies have hardly lost any of their popularity, none of the financial intermediaries have been imprisoned or even prompted the Swiss authorities to substantially tighten the Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA). And the local fiduciary and financial sector is not just content to develop offshore activities "Made in Switzerland" only in exotic countries.

The term “offshore” has a negative connotation but, contrary to some misconceptions, it does not refer only to “offshore” jurisdictions or tax havens such as the British Virgin Islands, Guernsey or Jersey but also conveys the notion of being outside national territory. So, in this case, a company is registered in Switzerland not for the purpose of conducting commercial activity there, but to benefit from local tax or regulatory concessions. In addition, Swiss banks still claim that they manage more than a quarter of the world’s cross-border assets, which makes Switzerland the leading offshore financial centre.

©

Denis Bailbouse / Reuters

©

Denis Bailbouse / Reuters

The postman and the mailbox

Public Eye has mapped the corporate structure of Switzerland’s most important hubs for domiciliary companies; from Geneva to Zug, via Ticino. The canton of Fribourg was also included in our survey as it’s also renowned for being home to a large number of shell companies. In these four cantons, we have identified nearly 33,000 shell companies. The direct consequence of this on the commercial landscape at these hubs is rows of buildings containing mailboxes for companies which struggle to claim a single employee and shell companies that flourish and die according to the vagaries of political and judicial turmoil.

For postal workers, the procedure is clear when the recipient is untraceable. A search notice is issued, a note is recorded on the pocket scanner to indicate that the recipient has disappeared, and the central AMP file for the postal workers will be up to date for the next round. What about the more complex cases? We’re talking about rental properties filled with sublets and their corporate counterpart, blocks of law firms, where a large number of domiciliary companies are hidden away, according to Michel Guillot, who has been in the profession for 25 years.

This is the common denominator among the four locations featuring in our research: a large number of law firms, fiduciary offices, notaries and other financial intermediaries, a significant proportion of which are devoted to creating companies and setting up complex corporate structures, often via other jurisdictions renowned for their lack of transparency.

Although legal, these structures make it possible to conceal certain transactions and/or hide the identity of the ultimate beneficial owner (UBO). The World Bank regularly expresses concern about this as part of its battle against white-collar crime.

“Nearly all cases of grand corruption have one thing in common. They rely on corporate vehicles – legal structures such as companies, foundations, and trusts – to conceal ownership and control of tainted assets,”

it warned in the introduction to its publication The Puppet Masters: How the Corrupt Use Legal Structures to Hide Stolen Assets and What to Do About It.

Before playing the role of postal worker, it’s a matter of defining the main characteristics of the companies we are seeking to identify. Here are some of the tell-tale signs to look out for:

- a lack of operational or commercial activity;

- no staff (except for managing directors and administrators);

- domiciliation with a fiduciary office, law firm or notary;

- the complexity of the structure (for example, with several organisational layers superimposed on each other before getting to a natural person); or

- the fact that it shares the same managing director or administrator with a large number of other companies. And even at a more mundane level:

- an abnormally low consumption of heating, electricity and internet data could also give some clues. But this latter information is not publicly available.

“Vaporous” nature of the local economy

©

Public Eye

©

Public Eye

Public Eye’s investigation reveals that Geneva has some 13,600 shell companies, spread across buildings where law firms and fiduciary offices administer their day-to-day affairs. “Low cost” facilitators are only too eager to offer their services via the internet to create a company in Switzerland without being domiciled there in a few clicks and in less than two weeks. Some even offer a corporate concierge service with Swiss numbers to almost look the part, as well as a service for redirecting phone calls and post for CHF 99 per month. And since Switzerland refuses to have a public register detailing the ultimate beneficial owners of the companies, which would make it possible to identify the natural persons behind the domiciliary companies, discretion is guaranteed.

The lack of transparency surrounding these companies makes quantitative research complicated. It’s difficult to establish a definitive figure for the number of shell companies that exist, but it’s possible to calculate an estimate using different databases.

The most basic method for doing this is to take the number of entries in the Geneva commercial register and subtract from it the number of telephone numbers for companies appearing in the search.ch register. We counted 45,351 Geneva-based companies as of the end of August 2020. Subtracting the 31,056 telephone numbers gives a difference of 14,295 companies. This is not the most accurate estimate, as a certain number of them may conduct genuine commercial activities, even though they are no longer entered in the phone book. Conversely, several fiduciary offices in Geneva offer a service including the allocation of a number with a local code.

The second method is to list, based on anonymous data from the Structural Business Statistics (STATENT) from the Federal Statistical Office (FSO), all companies which declare less than one full-time equivalent (FTE) post. Of the 36,927 companies accounted for by the FSO on the basis of OASI administrative data (companies paying contributions from the income threshold of CHF 2300 per year), 19,139 have less than one FTE post. To put it another way: more than half (51.83%) of Geneva’s economic base has less than one employee. This includes those legal constructs which only need a part-time administrator to manage their day-to-day business. Not to mention all the self-employed professionals (doctors, lawyers, etc.) who do not practise their occupation full-time.

The last method and the most refined that we have chosen is to “scrape” the data from the Geneva commercial register, which can be accessed via the Zefix.ch website more specifically the names of the company directors. This classification reveals people and firms administering dozens of companies, up to 167 for the most prolific among them. Therefore, these companies simply cannot have a real substantial presence. For the purposes of the analysis, we set a threshold of six managed companies (i.e. where the manager devotes less than one day per week to each company).

This resulted in 13,638 companies that we would describe as shell companies, corresponding to 30.07% of the companies entered in the Geneva commercial register.

By way of comparison, Geneva has 10,143 companies featuring c/o in the commercial register.

“Ghost” buildings

It’s an open secret. Creating companies in a manner which is fast and involves little red tape is one of the major assets of Switzerland as a financial centre. From a tax perspective, the most recent corporate tax reform led to Switzerland abolishing the status of “domiciled company” on 1 January 2020. Even without tax concessions, Swiss companies pay very low taxes by international standards. The profit tax rate in Geneva is 13.99% for companies, excluding the tax breaks negotiated on a case-by-case basis. By way of comparison, OECD members have agreed on a comprehensive corporate tax reform in the summer of 2021, which provides for a minimum rate of 15% on corporate profits.

After implementing this reform under pressure from the OECD, the abolition of special statutes still doesn’t mean that shell companies will disappear. In Geneva, the rate at which companies are being set up is so intense that postal workers are not the only ones struggling to keep up. The justice system is also overwhelmed and shady middlemen are cropping up again like weeds (see the box opposite).

More infos

-

Putting out one fire to start another

This is quite a rare occurrence, but some financial intermediaries end up being worried about the judicial ramifications of having created offshore companies. This is what happened in the case of asset manager Driancourt & Cie, formerly based at Cours de Rive 3, which was embroiled in a corruption case dating back to 2007. The Geneva-based company had been commissioned by Dredging International Services, the Cypriot branch of the Belgian oil group DEME, to transfer bribes to senior Nigerian executives in exchange for contracts for dredging work.

To conceal the payments, Driancourt & Cie, as well as its director Alain Driancourt, had created three offshore companies linked to bank accounts at Credit Suisse and EFG Bank, with several million euros in commission for the Geneva intermediaries. Following a report from the first bank, an investigation was launched in 2011. This led to a conviction by FINMA (Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority), which announced the winding up of the asset management company in August 2015. Alain Driancourt waited a mere three months to create his new company Driancourt SA, entered in the commercial register on 13 November 2015 at rue d'Italie 11. This address, in a pretty building near the Rond-Point-de-Rive, is home to 42 companies, including at least three fiduciary offices, with an average of 2.5 employees per company.

Whether it involves minimising their taxation, hiding transactions in a risky market or bouncing back quickly after taking a knocking from the courts, Swiss financial intermediaries always respond in an instant. Remember the Geneva branch of Rosneft Trading, sanctioned by the United States on 19 February 2020 for selling Venezuelan crude oil. The Russian company only needed a month to reappear under a different corporate name: Energopole. It was a Geneva-based fiduciary office which handled the creation of the company, as well as its accommodation in its premises on rue Mina-Audemars 3 (or rue de la Vallée 3 before the street was renamed in honour of this renowned Swiss woman in September 2020). There are 13 c/o addresses at this address, according to the commercial register, including twelve at the fiduciary office.

The plethora of company names with c/o addresses – such as the 136 companies at 8 rue du Nant in Eaux-Vives – still doesn’t attest that the companies have a real substantial presence. To go beyond the snapshot provided by the Geneva commercial register, we added another variable to our analysis: the number of employees in a full-time equivalent (FTE) post. The results are sometimes eye-catching. Of the 20 buildings with the largest number of companies (50 or more) in Geneva, only seven have an average of more than five employees. These include the Carouge shopping centre, the La Tour hospital in Meyrin, the Grangettes clinic or the World Trade Center – sites removed from our classification where, at first glance, commercial activity of a “substantial” size is operating.

What about the rest? Addresses which have in common a multitude of firms and companies operating in finance, the real estate sector or commodity trading. A recent FSO survey covering the whole of Switzerland confirms that of the 900 companies operating in the commodity trading sector, more than a quarter (26.4%) have no employees. Among the “ghost” buildings in Geneva, we should mention 15 rue du Cendrier, a building that has an average of 2.4 employees for 91 companies.

It was actually from this building that a seller of second-hand offshore companies provided an empty shell called Trekell to a controversial local lawyer for CHF 5000. Trekell then found itself at the heart of a forgery case involving fake videos, produced with the intention of accusing the cousin of a Kuwaiti sheikh of high treason, according to the newspaper Tribune de Genève. The trial, which was scheduled to take place before the Federal Criminal Court last February, has been postponed.

Another intriguing address is 18 rue de Genève, a building that looks available to rent, adjoining the Ecole de la Place-Favre in Chêne-Bourg. Our survey shows that 51 companies are domiciled there with an average of 1.4 employees per unit. This building is home to an old acquaintance of the Geneva branch of Mossack Fonseca: a fiduciary company which was once the auditor of the firm at the heart of the Panama Papers scandal. At that time, it bore the name of its founder, whose plaque is still on display at the entrance. Three months after the scandal, on 20 July 2016, the group changed the name of its Luxembourg parent company and also that of its Geneva branch, according to the entry registered in the Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce.

A dangerous game

Shell companies are not necessarily engaged in shady activities. Therefore, we are not claiming that all of these companies, or those who profit from their creation, are defying the tax authorities in their own country or are involved in any financial crimes. But it’s exactly this type of corporate structure that’s most often used when it comes to concealing beneficial owners in Switzerland, i.e. people who ultimately exercise effective control over companies or legal structures.

Or rather make your mind up based on the fact that almost half (44.36%) of the incidents reported to the Money Laundering Reporting Office Switzerland (MROS) involve domiciliary companies. What do these suspicions relate to? Often corruption cases, according to what is maintained by the Swiss authorities in a 2019 report. In almost 12% of these Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs), the legal entities involved are registered in Switzerland.

More infos

-

Steinmetz’s constellation of front companies controlled from Geneva

A “control tower” based in Geneva. This was the term used by the presiding judge at the Criminal Court of Geneva to sum up the activities conducted by Beny Steinmetz’s faithful administrator. In the dock alongside the Franco-Israeli mining magnate, his administrator was sentenced on 22 January 2021 for “allowing the implementation of the corrupt scheme” to obtain a licence to explore and exploit the vast Simandou iron deposit in Guinea.

Switzerland’s first major international corruption trial was also against the corporate manipulation going on in Geneva. To hide the corrupt schemes, Beny Steinmetz Group Resources (BSGR) employed the consulting firm Onyx Financial Advisors, as well as its former director, eventually hired by BSGR to manage its complex organisational structure, intended to camouflage the group’s real beneficial owners and obscure justice. “Everything was done from her Geneva office,” stated the judge while explaining the reasons for her verdict. She was the one who set up “the administrative and corporate aspects of the corruption operation and the steps to hide them through shell companies”, as well as complex sets of misleading accounting documents.

The former administrator received a two-year suspended prison sentence and a fine of CHF 50,000 for “bribery of foreign public officials” and “document forgery”. The Franco-Israeli billionaire Beny Steinmetz, who previously had his tax status in Geneva, was sentenced to five years in prison and a fine of CHF 50 million for having arranged a “corruption pact” with the wife of former Guinean President Lansana Conté.

Before ending up with this historic conviction, the Geneva justice system had to penetrate the smokescreen created by the layers of the BSGR structure. They included several Geneva shell companies – Frequence Holding SA, Terrane Holdings, Terrane Global Investments SA or BSG Real Estate (Switzerland) Sàrl – and also other offshore entities in Guernsey, Luxembourg or the British Virgin Islands.

The whole thing was overseen by the Liechtenstein-based Balda Foundation of which Beny Steinmetz and his family were the sole beneficiaries and his lawyer, Marc Bonnant, one of the three directors. This is the same Mr Bonnant who defended the businessman before the court, just one of a number of hats worn by this man who has become accustomed to major corruption cases, which doesn’t seem to bother him. Nor is this situation contrary to Switzerland’s regulatory framework. Beny Steinmetz and his former administrator have appealed their convictions.

From banks’ to lawyers’ secrets

What are the reasons for the key role played in this by Switzerland and its intermediaries? One is the extent of the lack of transparency which is still typical of its financial centre. Despite the coming into force of the measure making the automatic exchange of information compulsory in January 2017, the NGO Tax Justice Network, co-founded by Public Eye, ranks Switzerland in third place in its Financial Secrecy Index 2020, a global classification of jurisdictions which offer the widest range of tools to conceal assets. The Switzerland Global Enterprise (S-GE), the official Swiss export promotion organisation, even hires the services of local lawyers, fiduciaries and notaries who can “quite easily be appointed to the Board of Directors” of your company.

Statistics from MROS, the office which centralises and filters reports of suspected money laundering, suggest that lawyers often hide behind their professional secrecy. In 90% of cases, it was banks that passed on suspicions, often after the publication of an article in the press. Five lawyers or notaries also did this in 2019, which is 0.1% of the reports submitted to MROS that year.

It must be mentioned that lawyers are only subject to the Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA) when they manage assets on behalf of their clients, but not for their “advisory” activities. In March 2021 in the parliament, the revision of the AMLA ended with a victory for the lawyers’ lobby, who will be able to continue with their tax manipulation without being subject to due diligence. Lawyers are therefore still not obliged to inform the authorities of any suspicion of money laundering.

The profession is not going to reform itself on its own. This is the firmly held view of Andres Knobel, a specialist in tax affairs at Tax Justice Network, who presents the following metaphor: “It would be like the fox hanging around outside the henhouse, campaigning for the hens to be freed.” With the legislator’s reluctance to regulate these activities, Switzerland will remain a haven for foxes, and Geneva will be hell for postal workers.

More infos

-

A system full of holes but in the process of reform

Most of the lawyers we contacted declined to give any comment on the grounds that their sector of activity was no longer affected by this issue, or because they consider that it’s no longer relevant. “With the automatic exchange of information, offshore structures without any substantial presence are no longer recognised by the tax authorities, who still want to know the identity of the person or persons who control them,” says one tax lawyer. The automatic exchange of information, applicable since January 2017 with some OECD countries, does, admittedly, reduce the lack of transparency associated with some of these structures.

The disappearance of the special tax statutes and holding companies regime linked to the last corporate tax reform also makes some of these instruments obsolete, at least from a tax interest perspective. Tax expert Philippe Kenel has the following to say: “Switzerland is no longer the haven of confidentiality that it used to be. You use old concepts to refer to things that no longer exist.” The partner at the firm Python wants as proof of this the new tax rates on company profits.

When it comes to tackling money laundering, unlike with banks, which are directly controlled by FINMA, the Swiss financial watchdog has delegated the supervision of financial intermediaries to self-regulatory organisations (SRO). There are about 10 of them in Switzerland, and it’s up to fiduciaries, asset managers and other lawyers who provide financial advice to register with them. SRO members are then audited by SRO-approved auditors, who analyse the documents provided by their clients.

Although there are cases of financial intermediaries “operating without licence”, Norberto Birchler, former director of ARIF (French-speaking association of financial intermediaries) believes that the system works well. “There are certainly plenty of domiciliary companies in Switzerland. But in accordance with the AMLA, they do not have any legal personality, so they cannot be their own beneficial owner. We always refer back to the real owner of the company,” he says. At a personal level, however, he believes that lawyers should be subject to the AMLA when they set up companies. “This could not be introduced during the revision of the law in March; this is likely to happen during the next review, under international pressure.”

-

Methodology: Three methods for dealing with a sensitive subject in Switzerland

One thing must be said straight away: our data remains a screenshot of the corporate structure at a given time T. It reflects the economic structure of a given canton at the time we extracted the data from Zefix.ch. This delve into the central index of all the company names in Switzerland enabled us to perform a first mapping of the addresses featuring the most companies and those containing the most company names with c/o in them.

So we have identified tens of thousands of companies, from which the companies in liquidation must be removed. The large commercial centres are logically home to more than a hundred companies. Not to mention hospitals and clinics where practitioners register their centre of activity. The development of co-working spaces is also encouraging certain companies to group together at a single, identical address. We have therefore discounted these from the analysis.

The various commercial registers have also enabled us, through a technique of extracting digital data known as “scraping”, to establish a ranking in terms of the individuals and firms administering the most companies by canton.

We then had to look at the substance of these companies: their number of employees in full-time equivalent (FTE) posts. Anonymised data (without company names) is publicly available on the website of the Federal Statistical Office (FSO). It provides a reference for the companies – and the number of employees – based on their geographical coordinates. However, results for companies with less than four employees are not detailed, and the administration has again taken care to systematically replace the last two digits of the geolocation data to complicate the matter of identifying the companies. “Number of employees” seems to be regarded as highly sensitive data in Switzerland.

In order to obtain the unabridged data for 2018 (the latest statistics available at the time of the research), we had to sign a data protection agreement designed to limit our ability to disseminate too accurate results or for each individual company, or to reveal the identity of companies with fewer than four employees. It was therefore this third database which enabled us to calculate an average ratio of full-time equivalents per address. We used it to geolocate addresses via the Google Geocoding geolocation API. The address file has been supplemented by searches on Google Maps, visits to the different avenues and floors in the buildings themselves, along with searches through the directory search.ch. Having no phone number may be a tell-tale sign that the company doesn’t have a substantial presence.

When asked about the reasons for the confidentiality surrounding these statistics, the FSO merely reminds us that it “applies the legislation in force relating to data protection”, and refers us to a relevant web page.