Zug – an offshore paradise for shell companies

Romeo Regenass and Adrià Budry Carbó, October 5, 2021

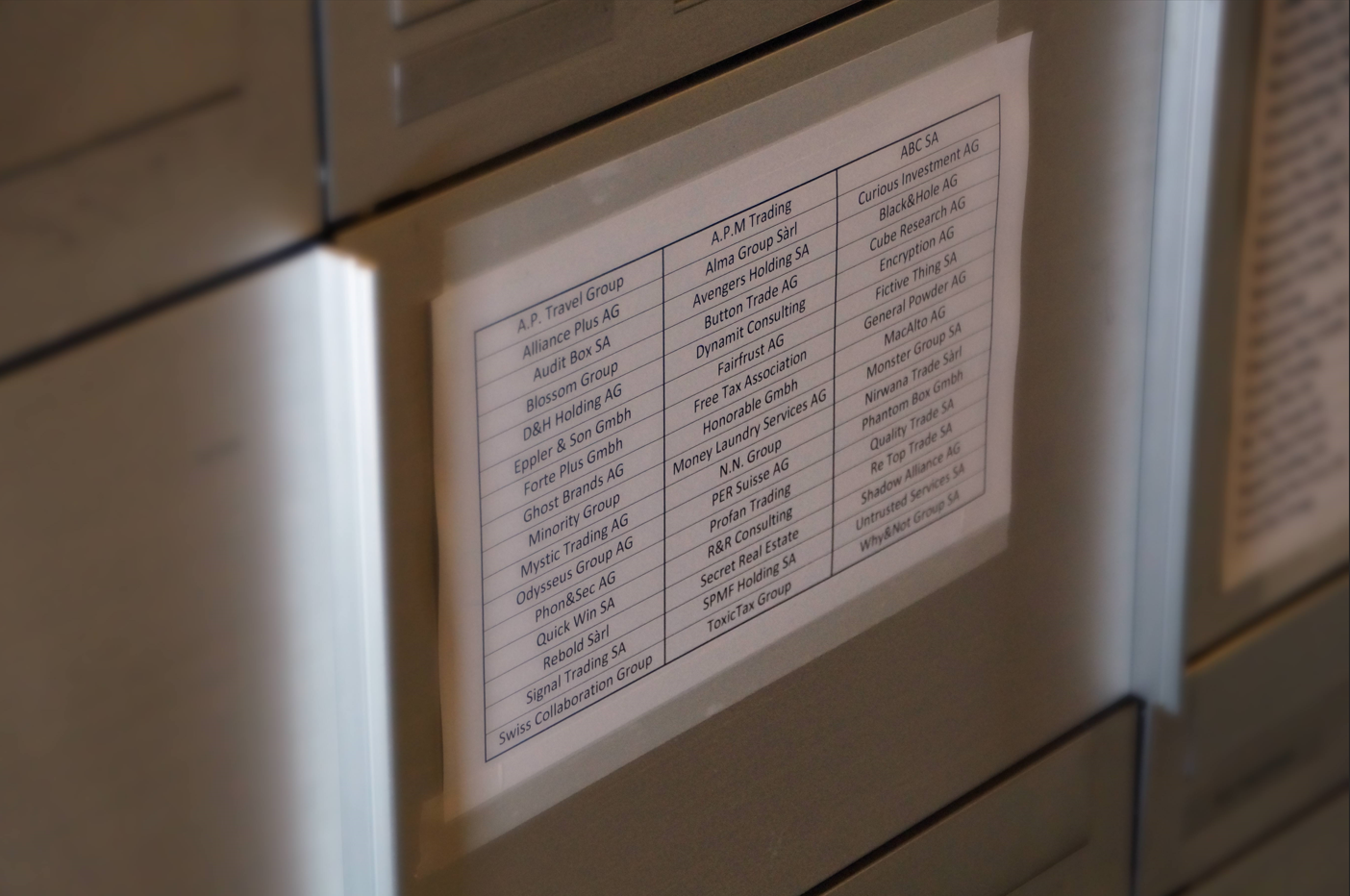

Poststrasse 30 in Zug’s new town – a few yards from the train station. At first glance, it’s an office building that looks like any other. The large board at the building’s entrance features 20 names of companies, spread across five floors. But the intercom system is not likely to be used that much. A total of six company names on makeshift labels are attached to the buttons of the intercom system, as well as an anonymous “Office 1st Floor East” and the general agency of an insurance company. With ten buttons that don’t have any labels on them, the building appears very anonymous. It’s quite obvious that most of the companies located here don’t expect any visitors.

It won’t come as any surprise to know that this office building is the number-one address for shell companies. So it’s not surprising either that only 23 of the 82 companies registered at Poststrasse 30, according to Switzerland’s Federal Statistical Office, are registered in the search.ch telephone directory. However, shell companies can often be reached via a fiduciary office or law firm, which grants them a domicile and takes calls for them; a business model that is highly popular in Zug.

©

Public Eye

©

Public Eye

Representation for CHF 95 per month

Domicile is available for shell companies in low-tax Zug at a bargain price. For instance, Domizilagentur GmbH offers for CHF 95 per month a c/o business address as the “company’s representation” with a “mail and parcel receipt” service at the centrally located Baarerstrasse 43. If you want the mail to be forwarded once a week, you pay an additional CHF 45 per month.

The basic fee for a business address without the somewhat innocuous addition of “c/o Domizilagentur GmbH” is already CHF 195 per month. The domicile provider contractually undertakes for this to provide the shell company with premises for shared use. This can also be just a meeting room; there aren’t any more options available for CHF 100 per month in an expensive area like Zug, but this is sufficient to meet the lax requirements of the Zug commercial register office.

The agency is also extremely cost-conscious in other respects. In early September 2021, it was looking for a person for “Administration in German” on the job portal kosovajob.com. Task: to edit and check Excel files. However, the job in an “office in the middle of Pristina (Kosovo)” requires not only a very good knowledge of German but also a university degree. Applications must be sent to the agency’s Swiss e-mail address.

There are quite a few service providers like the domicile agency in the canton of Zug. One of them runs the website briefkasten-zug.ch and offers a “virtual office”, while another explains under swiss-company-formation.ch why Zug is such an attractive location. Point 1: low taxes.

Tax haven

Having a shell company in the tax haven of Zug can, indeed, save a lot of money. However, a small real estate and architecture company had to learn that things don’t always work out as expected. In 2017, the Zurich Administrative Court moved the company’s headquarters from Zug to Winterthur by court decision. The registered office in Zug is obviously only a bogus domicile. The micro-enterprise registered in Zug since 2008 with a maximum of three employees did not concur with this decision and brought the judgment before the Federal Supreme Court. But just one year later, this court upheld the decision and the arguments submitted by the lower court. The company spends only CHF 100 per month on its “headquarters” at a c/o address in Zug. In Winterthur, office costs amounted to CHF 24,000 a year, whereby the tax residence had to be moved there. This marked a success for the tax offices in the Canton of Zurich and City of Winterthur. In fact, the change in taxing authority was even applied retroactively as of January 2013.

But the shell companies in Zug rarely make headlines in a local context. Most of the time they get embroiled in shady international deals. Whether it involves the Luanda Leaks, Panama Papers, Paradise Papers or now the Pandora Papers – Zug is always right at the forefront when the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) makes stunning revelations.

Zug-based and Swiss shell companies made their last major appearance in 2016 when the Panama Papers were disclosed - the confidential documents of the offshore service provider Mossack Fonseca, which were made public thanks to a huge data leak.

Scandal over Panama Papers had next to no repercussions

Five years ago, it was revealed that 1277 Swiss middlemen had set up more than 38,000 shell companies in the Caribbean via the Geneva branch of Mossack Fonseca. An investigation conducted by Public Eye in June 2021 showed that two-thirds of the 211 managing directors had disappeared into thin air, but at least 120 of the 153 Swiss law firms named in the Panama Papers (78%) were still active. And of the 821 other Swiss fiduciary offices and financial intermediaries involved, three quarters are also still in business (73%). The rest of the intermediaries are composed of unidentified companies.

As revealed by the “Pandora Papers”, a massive data leak from 14 offshore firms made public by the ICIJ, Swiss intermediaries continue to play a key role in setting up shell companies to conceal the origin of funds and their true owners. Of the approximately 20,000 offshore companies of the Panamanian law firm Alcogal, more than a third were linked to Swiss-based lawyers, fiduciaries or advisors. Their clients? Monarchs, despots of authoritarian countries or criminals.

The series of revelations therefore had no consequences at all: the domiciliary companies have hardly lost any of their popularity, none of the financial intermediaries have been imprisoned or even prompted the Swiss authorities to substantially tighten the Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA). And the local fiduciary and financial sector is not just content to develop offshore activities "Made in Switzerland" only in exotic countries.

Billion-dollar bankruptcy of Zug-based shell company

There is still regular mention of individual cases. For example, the Financial Times recently revealed that the New York hedge fund Lion Point Capital has filed a claim in Zug for damages amounting to one billion dollars against EY Switzerland, the former Ernst & Young. EY had audited the accounts of the Zug-based shell company Zeromax since its foundation in 2005. For the years 2008 and 2009, EY no longer provided an assessement of the annual reports. In 2010, the limited liability company, which had the minimum capital of CHF 20,000, went bankrupt and left behind a mountain of debt amounting to an incredible CHF 5.6 billion, of which CHF 2.5 billion are still untraceable today. Only the amount involved in the Swissair bankruptcy exceeded that figure.

Lion Point Capital had acquired a debt tranche from Zeromax’s bankrupt estate in 2019, which is why the hedge fund can now proceed as a claimant. Zeromax operated mainly in the Central Asian Republic of Uzbekistan through a network of other shell companies. It traded in commodities, especially oil and natural gas, and was considered for a time the largest employer in Uzbekistan.

According to the Financial Times, in the four years prior to bankruptcy, Zeromax paid, for instance, sums amounting to tens of millions for valuable jewellery, which the Uzbek president’s daughter Gulnara Karimova, known for her extravagant lifestyle, enjoyed. This came to light through assets confiscated by Swiss investigating authorities in 2016 at the Geneva-based private bank Lombard Odier. There were items of jewellery that Zeromax had paid for in safes leased by Karimova. Between 2004 and 2007, Zeromax is also said to have paid at least USD 288 million to offshore companies controlled by Karimova or her entourage, which served as a vehicle for laundering corrupt funds, according to the Swiss prosecution service.

Almost 33,000 shell companies in Switzerland

These shell companies are not only available in Zug. In order to obtain an overall view, Public Eye has mapped the key Swiss locations where they occur as part of a meticulous data analysis. From Geneva to Lugano and Zug to Fribourg, we identified almost 33,000 companies which are hugely lacking in any substantial presence. The immediate consequence for the corporate environment at these locations is that there is a considerable number of buildings with mailboxes displaying the names of countless companies which require virtually no premises and do not employ any staff. Not to mention a vast number of shell companies that keep the commercial register offices on their toes with their often limited service life.

Shell companies have the following main features:

- No operational or commercial activity on site

- No staff of their own (other than management)

- c/o address and/or registered office with a fiduciary or law firm

- Complex structure (e.g. with several superimposed organisational levels before a natural person features)

- Managing directors who manage a large number of other companies

- Unusually low consumption of heating, electricity and internet data (although this information is not publicly available).

In the case of Zug, Public Eye’s investigation has revealed that there are around 6300 shell companies which are housed in buildings where law firms and fiduciary offices conduct their daily business. And since political Switzerland still refuses to introduce a publicly accessible national register of the ultimate beneficial owners (UBO) of companies, discretion is guaranteed for the actual owners, which is another important locational advantage.

Lukashenko’s wallet in Zug

Politically exposed persons (PEPs), who are subject to stricter requirements than normal citizens with regard to anti-money laundering regulation, also like to use shell companies. The most recent example is a Zug shell company with reference to the Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko, according to the “Tages-Anzeiger”. The Minsk-based construction and property group Dana Astra, which is close to Lukashenko, is one of the dictator’s “wallets” in the view of the US sanctions authorities. These companies finance Lukashenko and his regime, are given preferential treatment when it comes to state contracts, and receive all sorts of reliefs, such as tax giveaways. This is why they have been on the sanctions lists of the USA and the EU since 2020, but also on that of Switzerland’s State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO).

In spite of this, Zug-based Dana Holdings GmbH, which is now in liquidation, enabled the Belarusian Dana Astra to appear on the Cbonds financial platform, for example, as part of a Swiss company specialising in investments in the real estate sector and developing residential, commercial and industrial buildings. Except that Dana Holdings only had a c/o address at the Zug branch of a large Geneva business law firm and, therefore, had no substantial presence. It can be assumed that the Zug shell company was also used for tax purposes.

The fiduciary and financial sector is not content with developing offshore activities “Made in Switzerland” only in exotic countries. Contrary to what is generally assumed, the English term “offshore” does not only refer, from a Swiss perspective, to foreign jurisdictions or tax havens such as the British Virgin Islands. The term refers to something that is located abroad from the point of view of an operator – and this foreign country is often also Switzerland.

Popular offshore location in Switzerland

Or as a Zurich law firm says on its website: “An Offshore Bank Account is a normal bank account located in a foreign country with a foreign jurisdiction. As the investor has no residence in the offshore jurisdiction, the authorities in the home country have no influence over his overseas bank account”. By the end of 2020, Swiss banks reportedly managed, according to their own data, a quarter of the world’s cross-border assets under management; in the first half of the year, they even rose by 6.9%. This makes Switzerland the world’s leading offshore financial centre – or “world market leader in cross-border private banking”, as the Swiss Bankers Association puts it. But “offshore” means that not only can accounts be opened in Switzerland, but also that companies can be set up.

More than 200 companies in one building

In addition to Poststrasse 30, mentioned at the beginning, there are a good dozen buildings in the canton of Zug in which 70 or more companies have their official headquarters, the vast majority of which have no substantial presence. Incidentally, one odd aspect of shell companies is that they don’t have their own mailbox, but share one with 70 or more other bogus companies. Sometimes the font used for the long company list is so small that the postman needs to have good eyesight to make sure that he/she puts the mail in the right box.

The number of employees per company is remarkably low at these locations. Many companies are actively involved in the financial or property sector as well as in commodity trading. The latter sometimes even seem to do without any staff at all. According to figures from the Federal Statistical Office for 2018,more than a quarter (26.4%) of the 900 companies operating in this sector nationwide have no employees. And almost one in four commodity traders in Switzerland is based in the canton of Zug.

Here are three more typical locations for shell companies:

- Baarerstrasse 2 in Zug: According to our research, 204 companies are domiciled in this office block. They include asset managers, law firms and fiduciary offices representing dozens of companies. On average, each company employs 2.4 staff.

- Bahnhofstrasse 21 in Zug: Located directly opposite the cantonal tax office, 75 companies have their headquarters at this address. Three fiduciary offices catch your eye with their mailboxes displaying long lists of companies. With 1.5 employees per company, the activity they operate doesn’t seem to be very labour-intensive. Of course, they are not all shell companies; many simply have their tax domicile at this address, while their actual business activity takes place in locations with less favourable tax conditions. This is why one of the trust companies also writes on its website: “Don't waste your time on paperwork, let us handle all the effort and we’ll provide you with the legally required staff.”

- Neuhofstrasse 5A in Baar: This address is home to a large fiduciary office, which also runs a business centre under its name, takes over the postal and telephone service and conducts correspondence for customers in several languages. This is so convenient that a total of 75 companies are domiciled here. But, on average, they each have just 2.7 employees.

If you take a stroll through Zug, no one notices these and other locations for shell companies, as they are office blocks just like any others. Just a glance at the mailboxes at the entrance shows how many companies co-exist in this tightest of spaces. But this kind of excessive density cannot harm the shell companies – few and far between as they are.

More infos

-

How shell companies promote corruption and money laundering

In addition to the large number of shell companies, the four business locations investigated by Public Eye – Zug, Geneva, Fribourg and Lugano – have something else in common: a large number of law firms, fiduciary and notary offices as well as other financial intermediaries and legal service providers, a significant number of which are involved in establishing complex legal corporate constructs. This is often the case in countries with a legal system known for its lack of transparency.

While these constructs are legal, they make it possible to disguise certain transactions and/or hide the true financial beneficiary. As part of its fight against white-collar crime, the World Bank regularly warns about this lack of transparency. “Nearly all cases of grand corruption have one thing in common. They rely on corporate vehicles — legal structures such as companies, foundations, and trusts — to conceal ownership and control of tainted assets,” it wrote in 2011 in connection with a book publication.

Not every domiciliary company is suspect

But not every shell company is necessarily engaged in shady activities. Nor do we claim that all of these companies, or those who profit from their creation, evade taxes or are white-collar criminals in their own country. However, domiciliary companies – i.e. companies that do not operate a trade, manufacturing or other commercial business in accordance with the Swiss Ordinance on Combating Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing – are most frequently used in Switzerland to conceal the “beneficial owners”. These are the people who ultimately exercise control over such companies.

The report “Korruption als Geldwäschereivortat” [Corruption as a predicate offence of money laundering] published by the Federal Government in 2019 also shows that around 44% of the business relationships that the Money Laundering Reporting Office learned about in 2017 on suspicion of corruption involved domiciliary companies; only 14% concerned operating companies and 41% natural persons. Of the reported business relationships to which legal entities were parties, more than 75% concerned domiciliary companies

Either way, the ability to set up companies without getting tied up in red tape is a key strength of the Swiss financial centre. In fact, as part of the most recent tax reform implemented on 1 January 2020 and under pressure from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), tax breaks for domiciliary companies were abolished. However, this does not mean that shell companies in Switzerland will now disappear.

Even without any tax breaks, Swiss companies pay very low taxes by international standards – and this is without taking into account individual agreements, which are even more advantageous for corporations. The Department of Finance of the Canton of Zug, for example, states that the profit tax rate for all companies is around 12% – depending on the specific local municipality and as a total of cantonal, municipal and direct federal taxes. By way of comparison, OECD members agreed in the summer of 2021 on a global corporate tax reform which envisages a minimum rate of 15% on corporate profits.

Inconsequential for taxpayers in Zug

In terms of paying taxes, shell companies make a modest contribution. At the request of Public Eye, Zug’s Finance Director Heinz Tännler stated that before the tax reform, domiciliary companies accounted for around 1% of the canton’s total tax revenue. “At the moment, the contribution is likely to be even lower,” said Tännler. “It’s so low that we completely ignore it for budget purposes.”

Tännler had also told the Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung in 2020 that the Zug government did not want to attract shell companies, but companies which were operationally active, created jobs and observed the laws. The current message is: “The Canton of Zug does not make any active efforts to attract these companies, but due to the freedom of domicile as well as the freedom of trade and commerce, it has no legal means of denying them domicile and the right to operate a business activity.”

The figure of 6300 shell companies calculated by Public Eye for the canton of Zug is considered by the Finance Director to be “significantly excessive”. However, this estimate contrasts with current information from the Zug Commercial Registry Office. At the request of Public Eye, it announced that by mid-September 2021, 7388 legal entities with a c/o address had been registered in the canton of Zug. The vast majority of these are likely to be shell companies. This includes those shell companies which do not have a c/o address because they have at least temporary access to office space through their domicile provider.

Even if the canton does not actively advertise them, shell companies are and will remain an important pillar of Zug’s economy. Bruno Aeschlimann, president of the Zug Fiduciaries’ Association, had predicted in 2016 “that they will more or less disappear in the foreseeable future.” Nowadays, he says that the decline is a lot slower than he expected at the time. “But there are few new ones.”

A Zug institution with a long tradition

Shell companies in Zug have their roots in a special law on the taxation of legal entities, which came into force in 1930 at the suggestion and with the active cooperation of Zurich lawyer Eugen Keller-Huguenin. Zug historian Michael van Orsouw described in 1996 in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung that the lawyer had worked for Zug because he saw no chance of success for his project in “socially divided” Zurich. He promised the people of Zug a golden future: “The tax power of the population will be increased, its general purchasing power will be boosted, and industry will receive many times more alimony; what tourism only makes possible by investing huge capital is achieved here by a few simple rates in the tax legislation.” These “few simple rates” characterise the canton of Zug to this day.

-

Methodology: Multi-level analysis of Public Eye

By the very nature of this activity, an exact figure cannot be put on the number of shell companies in Zug. Using various databases, Public Eye has succeeded in uncovering the world of shell companies. We used the following approach to do this:

- Firstly, we have deducted from the number of entries in the cantonal commercial register those for companies in the search.ch register. As of the end of August 2020, we counted 35,513 Zug-based companies in the commercial register. If you subtract the 11,103 telephone numbers, there is a difference of 24,410 companies (more than two thirds). This is not the most accurate estimate, as a certain number of them may conduct real commercial activities, even though they are not entered in the phone book, as entry is voluntary for companies as well as for private individuals.

- The second method is to list all those companies which declare less than one full-time position on the basis of anonymous data on the corporate structure from the Federal Statistical Office (FSO). This applies to more than 50% of Zug’s companies. Of the 17,085 companies recorded by the FSO on the basis of old-age and survivors’ insurance (OASI) administrative data, 8666 had less than one full-time position (whereby the FSO only covers companies that pay a minimum wage bill of CHF 2300 per year). This illustrates the lack of any substantial presence in a large part of Zug’s economy. However, all self-employed persons (doctors, lawyers and other freelancers) who do not work full-time also come under this category. Therefore, this estimate is too high on its own.

- And finally, to the third and most accurate estimate. We have analysed the names of all managing directors who feature in the Zug commercial register. This showed individuals managing dozens of companies, including even over 100 by the most productive among them. Companies managed by such an individual cannot possibly have any real substance to them. During the analysis, we set a threshold of six managed companies (i.e. the manager devotes less than one day per week to each). This resulted in 6306 companies that we would describe as shell companies, corresponding to 17.8% of the entries in the Zug commercial register.

Number of employees – a well-kept secret

Using the website Zefix.ch, the central directory of all company names in the Swiss Confederation, we then created an initial list of the addresses where most companies are registered and the ones with the most company names with c/o added. But there is a caveat with this in that the trend towards co-working spaces also means that numerous companies register at a single address. Therefore, we didn’t take these buildings into account in the further analysis.

In order to verify the substance of the companies, we determined the number of employees in terms of full-time equivalents (FTE). Anonymised data (without any company names) is publicly available on the website of the Federal Statistical Office (FSO). The number of employees the companies have is determined on the basis of their geographical coordinates. The Federal Office has even taken the trouble to systematically replace the last two digits of the geolocation data in order to make it more difficult to identify these companies. The number of employees in Switzerland seems to be highly sensitive information.

In order to obtain the unpublished data for 2018 (the latest statistics available at the time of collection), Public Eye had to sign a data protection agreement designed to limit our ability to disseminate too accurate results. But using this third database, we were able to calculate the average of FTEs per address. We were able to determine the geolocation data of the addresses via Google’s geocoding app. The resulting address file was then supplemented by searches on Google Maps, visits to the buildings themselves and searches through the directory search.ch.