Soft Commodity Trading Switzerland – the nation of oranges

Silvie Lang, 15. June 2020

©

Marcos Weiske

©

Marcos Weiske

Geneva is home to one of the three largest traders in the billion-dollar orange juice trade – the Louis Dreyfus Company (LDC). It is one of the largest agricultural traders in the world. It runs its global commodities business from Switzerland. LDC cultivates and processes oranges, and trades juice. Its product portfolio also encompasses grains, soy, coffee, cotton and sugar.

LDC is not the only large agricultural trader to carry out its global trade business in Switzerland. Cargill, ADM, Bunge, Cofco and Glencore all do the same. For the most part, this encompasses transit trade, i.e. they do not physically import or export goods. Our 2019 report entitled Agricultural Commodity Traders in Switzerland. Benefitting from Misery? shed light on this opaque sector, which feels at home in Switzerland where the commodities sector enjoys tailored tax regimes and lax regulation. According to our calculations (official figures on market share are not available), at least half of the global trade in grains, 40% of sugar, every third cocoa and coffee bean, 25% of cotton and 15% of orange juice is processed by trading companies based in Switzerland.

Louis Dreyfus Company – a giant family business

The Louis Dreyfus Company (LDC) is a private company registered in Rotterdam, Netherlands. Its operational headquarters is in Geneva. This is where LDC manages its trade in oilseeds, grains, rice, coffee, cotton, sugar, and juice, as well as its freight and finance businesses. Measured by turnover (USD 33 billion in 2019), LDC is the fourth largest trader and processor of agricultural products in the world, coming in behind Cargill, ADM and Bunge. According to its own figures, the company produces, processes, and transports 80 million tonnes of agricultural goods every year. It employs some 18,000 people and operates in over 100 countries.

The family firm was founded by Léopold Louis Dreyfus, who was from Alsace, in 1851. It is now firmly in the hands of Margarita Louis Dreyfus, the Swiss resident who has acted as chair of the board since 2011. Her husband, Robert Louis Dreyfus, left her and their sons a 61% stake in LDC when he died in 2009. Since then, she has progressively purchased other family members’ shares in the company and now owns 96.6% of the shares. For the share buyback of the last tranche of 16.6% in 2019 she received a loan of USD 1.03 billion from Credit Suisse, for which she had to use her shares in the company as security.

Dangerous concentration

It is not only the trade of soft commodities that is controlled by a handful of powerful companies. The consolidation process in the agro-food system has extended to all stages of global value chains – in particular the production and processing stages. For example, nearly three quarters of the global market of orange juice production is controlled by only three companies – Swiss trader LDC and Brazilian firms Sucocitrico Cutrale and Citrosuco.

The consolidation of market power is particularly prominent in Brazil, the main country where oranges are produced. Since the 1980s, large companies have successively purchased processing factories, taken over other companies, and increasingly squeezed smaller producers out of the market. Associtrus, the umbrella organisation representing Brazilian orange producers, estimates that since the beginning of the 1990s, over 20,000 agricultural producers had to give up producing oranges because it was no longer profitable. At that time there were still over 30,000 independent producers; now there are only approximately 7,000.

Their market power enables the three remaining large firms to influence the policy framework in their favour in both, countries of production and where companies are domiciled.

This gives them significant influence over pricing. In contrast to the numerous other producers who are poorly organised, they are able to determine the purchase price of oranges; at times they push the purchase price below the production price.

©

Marcos Weiske

©

Marcos Weiske

Flávio Viegas is in no doubt that "pickers" lives are far worse today than they were 20 years ago". These are not the words of a unionist, but the president of Associtrus, the Brazilian umbrella organisation for small- and medium-sized orange producers. According to him, it’s the fault of the powerful players in the industry "who no longer compete with one another".

The orange juice cartel

In 1999, the Brazilian anti-trust authority CADE launched an investigation into cartelisation in the orange industry. Who was in the dock? Cutrale, Citrovita (now known as Citrosuco), the cooperative Coinbra Frutesp (later bought by LDC), Cargill, Fischer, Bascitrus, Abecitrus, and the then industry association, along with nine other people – all accused of pushing the purchase price downward. The case was concluded in 2016, after the companies acknowledged the price fixing and paid 301 million reals (CHF 54 million at the current exchange rate) into a fund.

However, the situation has not improved. Most of those names have now disappeared, and the market has been reorganised around the three multinationals Cutrale, Citrosuco and Louis Dreyfus. The ultimate irony is that Flávio Viegas was himself the director of the cooperative Coinbra Frutesp before LDC took the decision in 1993 to become more than just a trader by acquiring plantations in Brazil. For many independent producers, the cartel is still up and running. Since 2009, the three giants have joined forces in the export association CitrusBR. According to its website, its main objective is to "defend the collective aims of citrus exporters in both the national and international [arena]", by "monitoring trade issues", "combatting trade barriers" and "promoting the sector’s image". Associtrus filed a complaint at a court in London in September 2019 to assert the rights of the approximately 500 independent producers that it represents. The umbrella organisation is seeking over 3 billion reals (more than CHF 540 million) of compensation for damage caused to its members by price manipulation. The case is pending.

"From farm to fork"

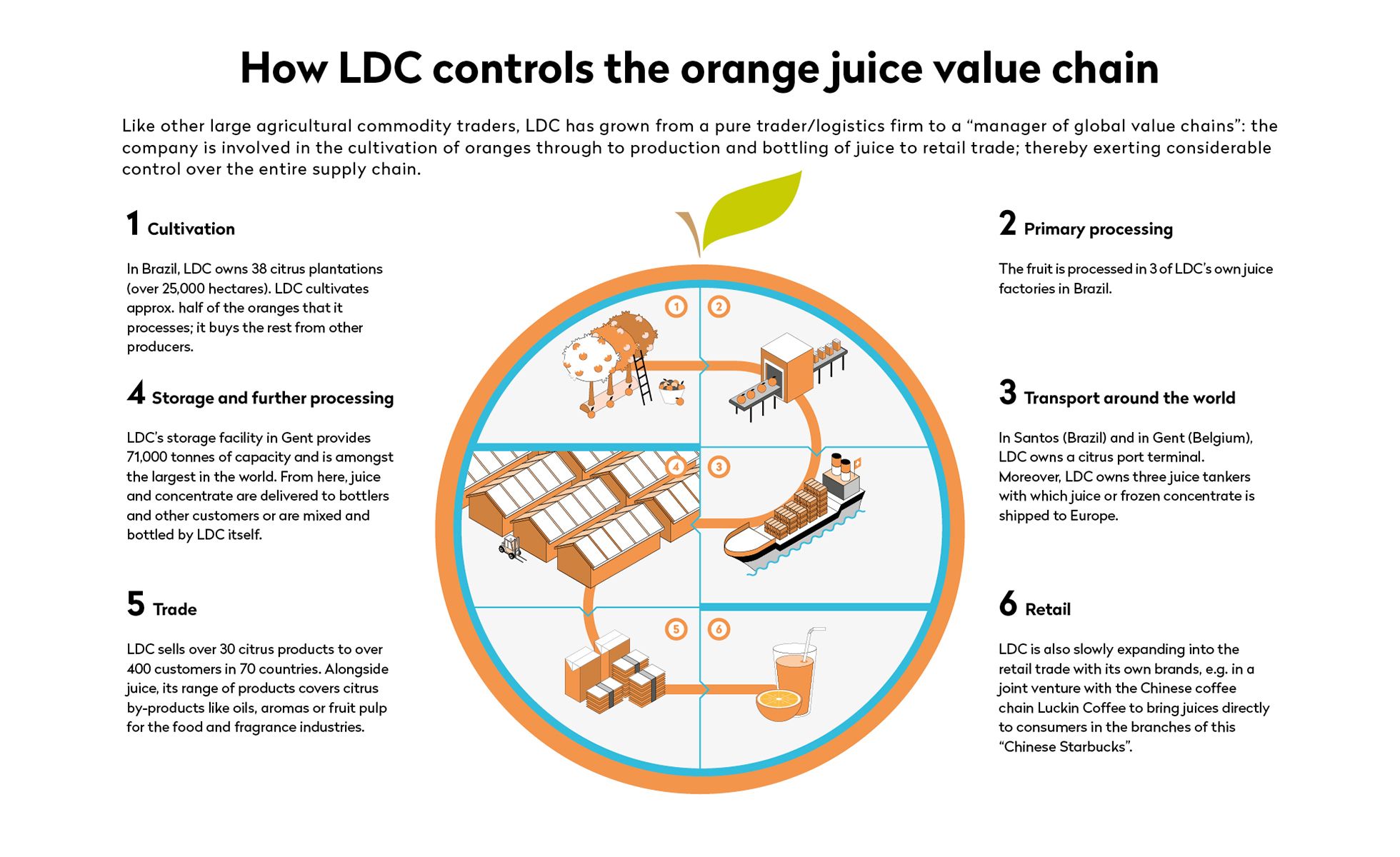

As in the case of other agricultural commodities such as cocoa, coffee, grains or soy, the growing concentration of market power in the orange juice business is being accompanied by a strong shift towards vertical integration. That means that companies are no longer purely trading companies but are expanding their activities and increasingly their sphere of influence, becoming involved in, for example, the cultivation of commodities. This gives them decision-making power over production and processing conditions throughout the value chain – from the cultivation of oranges at plantations to the production and bottling of juice. Essentially, they decide the conditions in which the commodities are cultivated, harvested, processed, traded and distributed.

For a long time, the sector has presented itself as a link between the producers (cultivation stage) and processors (producers of food, beverages or livestock feed), as actors who trade and transport goods on behalf of their customers. This image has long ceased to reflect the reality.

Agricultural traders have become "global value chain managers"

Alongside their own agricultural land, many also own maritime fleets and some even earn more revenue by producing food or livestock feed than they do with their own trading activities. This so-called "vertical integration" can even be seen in the companies’ slogans. For example, LDC promises a service that goes "from farm to fork". With its own plantations, warehouse infrastructure, processing plants, port terminals and freight ships, LDC is present along the entire value chain.

The orange juice sector provides a good example of this integration: according to its own figures, LDC owns 38 citrus plantations covering a total of 25,000 hectares of land under cultivation in Brazil. In addition, it owns three plants where oranges are processed into concentrate or juice. LDC employs over 8,000 people at its Brazilian plantations and factories. The company also owns port terminals used to store juice in the Brazilian city of Santos and Ghent in Belgium, and three juice tankers for maritime transport.

LDC delivers the fresh juice or concentrate either directly to customers, or it processes the raw product according to customers’ needs in Ghent. This is done either by mixing different qualities, adding fruit pulp or other fruit juices. The company sells over 30 citrus products to over 400 customers in 70 countries: alongside frozen orange juice concentrate and "not from concentrate" juice, it sells lemon and lime juice and spin-off products such as oils, aromas, dried shells (from which pectin can be extracted for the food industry), fruit pulp and fruit pulp pellets (which are used in animal feed for example).

©

Luckin Coffee

©

Luckin Coffee

In addition, LDC works in partnership with other large actors in the food industry which have their own brands as part of a strategy to move closer to end consumers. The Joint Venture (JV) with Chinese coffee chain Luckin Coffee, concluded in 2019, reflects this strategy. Through the JV, LDC is selling (initially) orange, lemon and apple juice to consumers in Luckin Coffee shops.

Millions of small-scale producers, a few powerful buyers

The vertical expansion of traders into the cultivation of agricultural commodities accentuates the power imbalance in the agro-food sector. The expansion into cultivation means millions of small-scale producers and workers are now faced far more directly with a few powerful companies.

This provides the companies with secure access to raw materials and more control over production conditions and prices. This is not only the case at their own farms, but at farms over which they exert de facto control due to their purchasing power, as can be seen from the example of the orange sector. As oranges cannot be stored for a long time, independent producers are often forced to accept the powerful buyers’ conditions. This means for example that at times they accept extremely low prices because otherwise their products would simply perish, and they would have no more income. By implication that means:

The more that trading companies move into the cultivation stage, the more they are directly responsible for the often exploitative conditions in which goods are produced.

The production of orange juice

Approximately 50 million tonnes of oranges are produced globally every year. They are primarily cultivated in tropical and sub-tropical areas around the equator – known as the "citrus belt". Brazil is the largest producer country: every year approx. 15 million tonnes are cultivated there. China is the second largest, producing approximately 7 million tonnes, ahead of European Union countries who produce over 5 million tonnes.

Well over 40% of all oranges cultivated globally are processed into juice, most of which is used to make concentrate. In the largest producer country, Brazil, around two thirds of juice produced is used for concentrate. In contrast to China and the EU, Brazil has specialised in processing and exporting orange juice and holds an 80% share of the export market. Mexico and the EU are the second and third largest orange juice exporters, while Chinese oranges are cultivated primarily for domestic consumption.

Frozen and concentrated

There are numerous different varieties of oranges, some of which are particularly suitable for making juice. Most producers cultivate different varieties that ripen at different times in a bid to supply the market nearly all year round. To produce orange juice concentrate, the aroma is removed from the fresh juice and boiled down to around a sixth of the initial volume. The concentrate is then frozen for storage and transport.

Before it is consumed, water, essences and – if desired – fruit pulp must be added to the concentrate. This is done by "bottlers", i.e. large drink producers or small fruit juice producers. They usually source the concentrate from more than one trader (LDC, Cutrale or Citrosuco); the large global drinks producers like Coca-Cola or Pepsi often have a main supplier. Alongside direct purchases from orange juice traders, frozen orange juice concentrate is often traded on agricultural exchanges. Finally, the bottlers sell the juice to retail traders who sell them to customers as either a name-brand or their own-brand product. The EU has the highest per capita consumption of orange juice, followed by the US.

Little transparency

Approximately 56 million litres of orange juice were sold in Switzerland in 2019. That equates to approximately 6.5 litres per person. It is difficult for consumers to tell the origin of the juice they buy. The packaging of a range of brands does not state the country of origin of the oranges at all, while for other brands more than one country of origin is named. Retail stores such as Migros and Coop do not state whether any of the three large traders Cutrale, Citrosuco and LDC are involved in the production or trade of the juices they sell. They do not provide any information about the suppliers on the ground. Information pertaining to the countries of origin was only provided upon request for organic or fair-trade juice.

-

©

Marcos Weiske

©

Marcos Weiske

-

©

Marcos Weiske

©

Marcos Weiske

-

©

Marcos Weiske

©

Marcos Weiske

Labour and human rights violations

As with many other agricultural commodities, producing oranges is labour-intensive. At large plantations, upkeep of the soil and trees is mechanised, but the fruit is still usually harvested by hand. This is physically strenuous work, which is often done under blazing sunshine or pouring rain. Workers pick oranges, load them into bags and carry these heavy loads to collection points. During the harvest, risks include falling from ladders and injuries from the thorns on orange trees; holes dug by armadillos and snakes pose further difficulties. In addition, there are cases of workers being poisoned while spraying pesticides because there is a general lack of suitable protective clothing and training. Orange monoculture is extremely vulnerable to disease and pests; pesticides are therefore used intensively.

And workers are mostly risking their health for a pittance.

Wages are usually comprised of fixed pay and a component linked to productivity. They therefore depend on how many oranges are harvested per year. Lucky workers manage to earn the statutory minimum wage (which is far from guaranteeing a living wage), and many do not even reach the statutory minimum – a clear violation of Brazilian labour law and internationally recognised human rights.

The orange sector typifies many of the fundamental and systematic problems associated with the cultivation of agricultural commodities and which cause widespread and serious labour and human rights violations. Millions of people in the agricultural sector around the world carry out strenuous labour, yet do not even earn a living wage or income. The agricultural sector is a high-risk sector for forced labour, which affected over two million people in 2016 according to ILO estimates. It is also high risk for child labour. The ILO states that 108 million children work in the agricultural sector under exploitative conditions. The health risk in this sector is very high. The ILO estimates that annually at least 170,000 agricultural workers lose their lives due to their work and that millions suffer serious injuries or become ill, often in connection with the application of highly hazardoius pesticides.

Land conflicts are another widespread problem; often caused by the acquisition of large swathes of land for the cultivation of soy, palm oil or sugar cane. In addition, the agricultural sector is by far the largest driver of global deforestation. Commercial agriculture causes – in particular for livestock breeding and soy cultivation – up to 80% of the deforestation in the Amazon rainforest, according to a study commissioned by The Dialogue, a network dedicated to promoting social justice in Latin America.

Business with politically exposed persons, corruption and tax offences are no rarity in the agricultural commodities trade. This includes manipulating prices of internal transactions, so-called transfer pricing to artificially move profits liable to taxation to another jurisdiction. There is a recent example of this in the orange juice industry: in 2019 approximately 85% of orange juice exported from Brazil was sold to entities abroad belonging to the same company – at internal prices that were up to 30% below the market price. The Brazilian tax authorities estimate that they have lost over 450 million dollars in tax revenues in the last five years.

The causes of these widespread violations lie in the imbalance of power between large agricultural traders and poorly organised small-scale producers and workers

The extremely imbalanced power and negotiating positions entrench a system that primarily benefits large multinational companies to the detriment of millions of people involved in the production.

Our demands: transparency and regulation

Companies with a large market share and significant influence over conditions of production should no longer be exempt from responsibility and must safeguard fundamental human rights in their supply chains.

With regards to the conditions in which agricultural commodities and in particular oranges in Brazil are produced, Public Eye demands that agricultural commodity traders, and above all LDC:

- Provide greater transparency along the supply chain and above all disclose suppliers to ensure traceability;

- Comply with all internationally recognised labour and human rights in the production of agricultural commodities, with a particular focus on enforcement among suppliers;

- Formalise employment relationships to guarantee a minimum level of legal certainty for all employees in the supply chain;

- Guarantee nationally uniform labour protection in collective agreements with different trade unions, so that all workers are afforded the same protection;

- Guarantee that workers’ health is protected by providing them with appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) free of charge and inform them of how to use it correctly;

- Swiftly guarantee that all workers receive at least the statutory minimum wage, regardless of level of productivity;

- Openly commit to ensuring all workers receive a living wage in the medium term, and to industry-wide efforts to develop a corresponding living wage benchmark and implementation plan with specific targets including deadlines, and milestones.

As the home state of global agricultural traders, Switzerland also bears a responsibility. Public Eye therefore calls on the Swiss government and parliament to:

- Guarantee transparency for the agricultural commodities trade in Switzerland, in particular by regularly disclosing relevant and comprehensive statistical data on numbers of companies and employees;

- Use regulation to ensure that Swiss agricultural traders respect internationally recognised human rights, and implement human rights and environmental due diligence as outlined in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights;

- Guarantee access to judicial as well as extra-judicial remedy for victims of human rights violations caused by Swiss agricultural traders;

- Guarantee that competition policies and practices take account of the negative impacts of market concentration and abuse of market power by Swiss agricultural traders along global value chains.