Instant sustainability Why the Nescafé Plan fails to benefit farmers

Carla Hoinkes and Florian Blumer, 18. June 2024

While millions of coffee farmers around the world live in abject poverty, and countless workers toil in degrading conditions on coffee farms, the sale of coffee generates several hundred billion US dollars every year. The global market is constantly growing – indeed, demand could double by 2050 – while retailers and coffee roasters in particular are consistently making huge profits.

The profitable roasting business is controlled worldwide by an ever-decreasing number of multinational food and beverage companies. The undisputed world number one is the Swiss group Nestlé, ahead of the US group Starbucks and the Dutch conglomerate JDE Peet’s.

Nestlé roasts at least one in ten coffee beans harvested worldwide, and generates a quarter of group sales from coffee, a growth business, which is its largest product division: CHF 22.4 billion in 2021. The export of its Nespresso capsules, which are produced exclusively in Switzerland, has helped to make Switzerland the worldwide leader in roasted coffee exports in terms of trade value. However, the group’s key coffee brand worldwide is Nescafé. Its factories, which produce mainly instant coffee, as well as cheaper capsule coffee under the Dolce Gusto brand, use up at least 80 percent of the coffee volume procured by Nestlé worldwide – more than 800,000 tonnes annually. Mainly thanks to owning the world’s biggest coffee brand, Nestlé leaves the competition far behind in the sale of instant coffee.

Swiss coffee - what else?

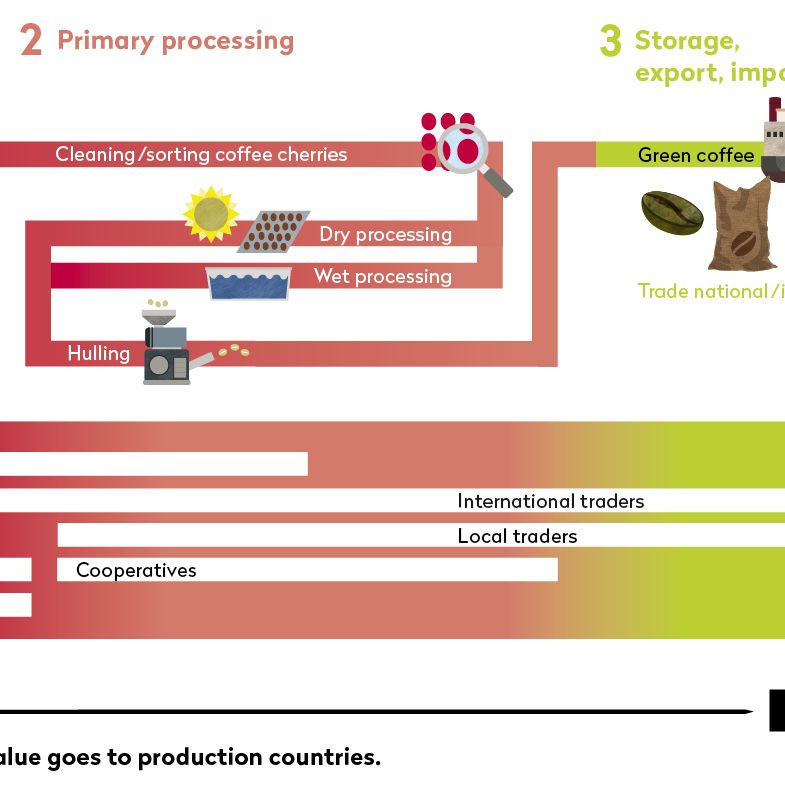

As a rule, roasting companies like Nestlé do not buy their coffee directly from coffee farmers or farmers’ cooperatives, but from local intermediaries or international traders – in other words, from large corporations that control the export and import, often the primary processing, and sometimes even coffee growing in the producing countries.

The world’s largest coffee trader, the Neumann Kaffee Group, headquartered in Hamburg, runs a large part of its trading business from Zug, and the next five largest corporations – Ecom, Ofi, Sucafina, LDC and Volcafe – are either headquartered or have their operations centres in Switzerland. This is also true of many smaller coffee traders. According to our estimates – there are no official figures available – trading of more than half of the global green coffee volume is conducted via Switzerland. This makes Switzerland the largest coffee trading centre in the world.

Even though in most cases the product itself does not physically enter Switzerland, it is currently the second largest coffee exporter after Brazil in terms of trade value. In fact, an export value of almost CHF 3.3 billion in 2022 even makes Switzerland the number one exporter of roasted coffee in the world. This figure is almost 1.5 times as high as the exports of its largest competitors, Italy and Germany. Since 2002, the export volume has rocketed by a factor of almost 19 to 109.4 million kilograms, while the value per kilogram has doubled. A major contributor to this unprecedented upswing is Nespresso, whose global sales have increased 18-fold since 2002 and whose factories, based in Switzerland, produce, according to our estimates, roughly 7 million capsules every year, mostly for export.

©

Lela Beltrão

©

Lela Beltrão

Drinking Nescafé to make the world a better place?

On the Nescafé website, the Swiss company promises: « We're using our global scale for good, one cup at a time.» This is mainly down to its flagship sustainability programme, the Nescafé Plan, which was launched in 2010 to improve value creation worldwide « from farmers to consumers to us », as the then CEO Paul Bulcke, and current Chairman of the board, put it. In 2022, Nestlé announced that it had invested over CHF 350 million, distributed 270 million coffee plantlets and held 900,000 training courses as part of the Nescafé Plan. All with the aim of improving the lives and incomes of countless farmers – especially in Brazil, Vietnam, Mexico, Indonesia, Honduras, Côte d'Ivoire and Colombia. At the same time, the company announced that it would continue the Nescafé Plan, with a new focus on climate-friendly agriculture, until 2030. According to the advert, with every cup of Nescafé they drink, consumers could “make the world a little bit better”. However, the reality is different for the coffee farmers, as we highlight in the report from the Soconusco coffee region in the Mexican state of Chiapas (see page 5), where many are now bitterly disappointed by the programme and are protesting against Nestlé’s disastrous purchasing policy, which keeps them in poverty and robs young people of their future prospects.

Public Eye's reportage (2024) : « High hopes, low prices : how Nestlé is driving Mexican coffee farmers to ruin »

Coffee farmers in Chiapas have to compete with cheap Robusta coffee, which Nestlé imports in large volumes from Vietnam, and especially Brazil. Thanks to irrigation, a lot of fertilizer and shadeless intensive monocultures, the Robusta coffee Nestlé needs to produce Nescafé instant coffee is mass-produced there in a particularly cost-effective manner. Robusta varieties are considered to be more resistant and easier to grow than Arabica varieties, but also inferior in quality. At present, almost 70 percent of the world’s Robusta comes from Vietnam and Brazil, a fifth of the total from the Brazilian state of Espírito Santo alone, where the flat land, unlike most other coffee-growing regions, allows partial mechanization of the harvesting operation.

Nestlé also sources large quantities of this coffee, which is called conilon in Brazil, in Espírito Santo. Journalists from the Brazilian reporters collective Repórter Brasil travelled to the region for Public Eye during the 2023 harvest season to find out under what conditions the coffee, which Nestlé says is also “responsibly” produced, is grown there.

The cost of mechanization

In May 2022, coffee farmer Rogéria Silveira, who was 41 at the time, lost her left forearm. The tarpaulin covering the coffee harvester at her conilon farm in Espírito Santo had slipped, and she had to put her arm into the machine to put it back in place. But her hand got stuck and, in a panic, she let go of the controls and then “the cylinder turned and tore off my arm,” she explains. In June of that same year, 24-year-old farm worker Pablo Henrique Souza Fabem also had an accident. He and his colleagues had to reinforce the tarpaulin with a rope because the coffee branches on it were too heavy from the rain of the previous day. “It all happened very quickly,” explains Claudio Rizzo, owner of the Santa Luzia farm in Nova Venécia, where the accident occurred. “The rope and tarpaulin wrapped around his leg and he was pulled into the machine.” Rizzo says he hurried to turn off the machine, but couldn’t do so immediately as there was no emergency button. “Pablo’s leg was severed and he suffered serious internal injuries,” says the coffee farmer. Pablo Henrique Souza Fabem died in hospital the following day.

“Many of these machines don’t even have an emergency shutdown”

The 2022 harvest season saw a total of seven amputations and two deaths in Espírito Santo, according to the authorities. From January to July 2023, 16 accidents were again recorded in the region. The converted machines, originally developed for bean cultivation, weigh about four tonnes and have tarpaulins up to 100 metres long on which the workers throw the branches of the coffee plants. The machine pulls in the tarpaulin, chops up the twigs and separates the coffee. Although these machines have been used for over 10 years, the authorities have only recently become aware of the problem due to the increased number of accidents reported. “The machine often has trouble pulling in the coffee branches, in which case the worker has to help them along,” explains public prosecutor Fernanda Barreto Naves in São Mateus. Therefore, accidents usually affect the upper limbs. “Many of these machines don’t even have an emergency shutdown,” deplores the public prosecutor.

-

©

Lela Beltrão

©

Lela Beltrão

-

©

Lela Beltrão

©

Lela Beltrão

-

©

Lela Beltrão

©

Lela Beltrão

The harvesting machines, which are mainly available to the larger farms, allow significant cost savings, which puts these farmers in a slightly better position overall than those in Chiapas, Mexico. But their income is still modest. A recent analysis performed by the Global Coffee Platform suggests that, in particular, smaller producers with less than 50 hectares of land do not earn enough to maintain a decent standard of living. Although their results cannot be generalized due to the small number of Robusta farms included in the analysis, conilon farmers in Brazil generally earn significantly less than Arabica producers.

Evidently, even the Nescafé Plan cannot change this situation, as confirmed by several participants in the programme. If anything, the contrary is true. Since Nestlé or its intermediaries – including local intermediaries and international trading groups such as Volcafe from Winterthur, Switzerland – often pay lower prices, they usually prefer other sources according to the farmers, who, unlike the producers in Chiapas, can choose between several Robusta buyers.

Finding other work elsewhere

According to Idalino Agrizzi, he has needed about three times fewer harvest workers since his farm was mechanized. However, like all the Nescafé Plan farmers interviewed in the region, he complains about an acute labour shortage. Harvester João Santos explains that he and his colleagues look for work elsewhere whenever possible. Wages are low and coffee-harvesting is very strenuous work. Another factor is the lack of wage security, because – as is customary worldwide – payment is made based on the amount of coffee cherries picked and, in the case of the partially mechanized harvesting, according to the number of coffee bushes cut. This can vary greatly depending on the weather, the productivity of each plant and the physical resilience of the worker. Another problem is the incomprehensible wage deductions to cover the mostly very basic accommodation and often unbalanced and unhealthy diet given to workers.

From the on-site interviews, it became clear that only a fraction of the added value goes to the workers.

No systematic surveys on the earnings of harvest workers have been conducted in Espírito Santo. However, those conducted in Minas Gerais, where a large proportion of Brazil’s coffee is produced, show that their average wages are mostly inadequate in terms of providing a living wage. It’s also clear from discussions held locally that workers there only receive a fraction of the added value. They receive the equivalent of about CHF 10 for four bags (240 kilograms) of coffee cherries, which are then processed into a 60-kilo bag of green coffee. The middleman pays the coffee farmer about CHF 120 for the bag, and sells it on to Nestlé for about CHF 170 after the coffee beans have been prepared, which can produce roughly 25 kilograms of instant coffee. The sale price for this quantity of finished Nescafé in the retail sector ranges from CHF 700-1000 in Brazil or CHF 1700 to 2000 in Switzerland, depending on the product.

-

©

Lela Beltrão

©

Lela Beltrão

-

©

Lela Beltrão

©

Lela Beltrão

-

©

Lela Beltrão

©

Lela Beltrão

Worker João Santos (not his real name) explains that harvesting by hand is more strenuous, but mechanized harvesting is more dangerous, because of the sickles he and his colleagues use to cut off the coffee branches, as well as the harvesting machines, which are a hazard to all those who operate them or are near the tarpaulin. Indeed, in Autumn 2022, coffee producers and machine manufacturers voluntarily committed themselves to minimum safety standards, including the installation of a mechanism for stopping machines in an emergency. However, according to the local authorities, these standards are rarely implemented. The use of non-safety-compliant machines was also found on Agrizzi’s Nescafé Plan farm in July 2023.

Producer Fernando Catelan, who is also a Nestlé supplier, is one of the few producers who has replaced the old machines with compliant ones. Since then, the accident rate has dropped by 90 percent, according to this Robusta producer. However, the defective machines usually continue to be operated. Even Fernando Catelan has sold his – to another farmer in the area.

©

Lela Beltrão

©

Lela Beltrão

Slave-like working conditions

In addition to low wages and the risk of accidents, there have been repeated labour-law violations in the region. In 2022 and 2023, at least two farm owners involved in the Nescafé Plan were also fined by the authorities; for example, because they did not provide workers with toilets or the necessary protective equipment, and did not authorize them to take rest breaks when performing strenuous tasks. In both these years, 30 coffee workers in Espírito Santo were also freed from slave-like working conditions. During the same period, there were several hundred similar cases throughout the whole of Brazil, with experts assuming a high number of unreported cases. Those affected do not receive any drinking water, live in the worst accommodation – sometimes without toilets – work without a contract or are paid irregularly. Some of them also have their passports confiscated, which means that they are stuck on the farms.

Such conditions have also been repeatedly found on certified farms that supply Swiss coffee traders. which even included in 2019 a farm that had been awarded the Nespresso AAA seal. It’s not possible to determine whether Nestlé purchased coffee from producers affected by these issues in Espírito Santo in 2022 and 2023.

Issue of sustainability on the cheap

Nestlé primarily uses certification by 4C (Common Code for the Coffee Community) as “proof” that the coffee procured under the Nescafé Plan is “sustainable”. This industry standard was launched in the 2000s by the German Coffee Association, which was founded by roasting and trading groups, and the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, and was jointly developed by Nestlé. The code’s requirements hardly go beyond existing statutory requirements, and studies show that its enforcement is weak compared to other certification schemes. At the time, the founders were convinced that it was precisely such a low-threshold offering – for roasting companies like Nestlé, 4C certification is comparatively cost-effective – that it would make it possible to bring ecological, social and economic sustainability to the mass market. Even then, 4C saw itself as an “entry-level standard” that would encourage companies to switch to tighter certification schemes later.

But in Nestlé’s case, this prediction was not to come true. The company still bases its promise to use 100 percent “responsibly” sourced coffee by 2025, primarily under the 4C framework. In 2022 alone, Nestlé bought 629,000 tonnes of 4C green coffee.

©

Lela Beltrão

©

Lela Beltrão

The coffee that Nestlé sources in Chiapas, Mexico and in Espírito Santo under the Nescafé Plan is also 4C certified, thereby supposedly making it “sustainable”. However, a different picture emerges on the ground. Farmers and workers benefitted little or not at all from certification, the implementation of which seems to be poorly monitored locally.

For example, the farmers in Espírito Santo confirmed that although audits are conducted, they are comparatively “relaxed”. Notice is even given about supposedly “unannounced” audits at least 24 hours in advance – a ridiculous practice that has long been criticized. In terms of working conditions and workers’ remuneration, 4C’s requirements are weak, as confirmed by local experts. And in general, the lack of transparency makes independent inspections more difficult or impossible, as 4C does not disclose its certified farms.

In particular, the voluntary and locally negotiated 4C price mark-up makes no difference to certified farmers in Mexico or Brazil. In Espírito Santo, farmers receive the equivalent of just one centime per kilogram of coffee. But the measures required for certification incur costs, while the price of the coffee is simply too low for the farmers to improve their income, as they can confirm.

Studies show that voluntary certification schemes generally have, at best, marginal positive effects on the income of coffee farmers. Another factor is that low-requirement standards, such as 4C, fundamentally undermine the effectiveness of certification. The roasting companies’ striving for 100 percent “responsible” coffee at a low price has not brought sustainability to the mass market, but has rather triggered a “race to the bottom” in which certifications undercut each other in terms of quality. Nestlé and 4C are the prime examples of this damaging mechanism. The Swiss company promises sustainability in coffee growing but, in practice, prioritizes purchasing the raw material at the cheapest possible price.

This means persistently low incomes for producers, which in turn results in low wages for workers and inhumane working conditions on the plantations. And in Chiapas, smallholder farmers must watch their children emigrate because they no longer see any future in coffee growing, which was once a source of pride for their families.

Our demands

More infos

-

On Nestlé, the roasting industry and all coffee traders

- To ensure that labour and human rights, including the right to a living income, are respected throughout the value chain, companies must adopt verifiable measures with a set timeframe. With this in mind, they must guarantee fair pricing as well as long-term trade relationships and transparent payment terms in their sourcing practices.

- In addition, there needs to be complete transparency throughout the supply chain – from the buyers via the intermediaries to the coffee farms.

-

On certification bodies

- Organisations like 4C should make the payment of a living income price to farmers and living wages to workers a prerequisite for certification.

- In their own best interest, they must guarantee the enforcement and independent monitoring of certification requirements. This includes transparency throughout the certified operations. They should also ensure that instead of small producers, the large buyers, i.e. the trading and roasting groups, bear the costs and risks incurred in the certification process.

-

On the politicians in the countries where the coffee companies are based

Since voluntary self-regulation has failed, governments and parliaments must legally oblige the companies responsible to adopt the above measures. This is especially true for Switzerland, as the home of the largest coffee roaster and a global hub for the coffee trade. For example, the following political instruments

could be used to achieve this:

- Mandatory due-diligence obligations for companies in the area of environmental and human rights, which must also include the implementation of the right to a living income for farmers and living wages for workers along the supply chains, as provided for in the EU Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence, adopted in May 2024.

- Regulations against misleading sustainability marketing, as they are currently being discussed in the EU Parliament under the term “Green Claims”, whereby social sustainability should also be taken into account.

- Measures ensuring transparency in the value chains, as well as a commitment to fair purchasing practices and the prevention of the exploitation of market power (also applies to production countries).

Coffee report

The full report « Instant sustainability : why the Nescafé Plan fails to benefit farmers » (2024) is available for download in German, French and English.

Photo 1 : Coffee bushes stretching as far as the eye can see: more than 1000 hectares of Robusta monoculture on a Nescafé Plan farm in Águia Branca, Brazil. | © Lela Beltrão

©

©