Price setting: the power of pharma

©

Shutterstock

©

Shutterstock

Price is a crucial factor for low- and middle-income countries whose healthcare budgets are limited and where the frequent absence of a health insurance system requires patients to pay for drugs out of their own pocket. However, price is also an important factor in rich countries, as it can result in decisions on rationing and undermine universal health coverage.

The pharmaceuticals industry justifies the power it has to set prices on the grounds of the large investments it says it has to make in research and development (R&D). However, it refuses to provide any transparency regarding the amounts actually invested. Therefore, in 2022, we estimated the R&D costs for six cancer drugs and calculated the profit margins for Switzerland. This study highlighted that, even after accounting for the cost of failures, large pharmaceutical companies are achieving profit margins ranging from 40 to 90%. This also applies to treatments that will continue to benefit from patent protection for many years to come as the margins they make continue to grow.

Even though prices can vary greatly from one country to another, they are benchmarked against the (poorly controlled) price set for the United States market. Protected from any competition while their patents are still in force, pharmaceutical giants impose their “global prices” all over the world. Their business model is built around highly profitable flagship products that are popular with investors. And for good reason: the annual turnover from each of these blockbusters is in excess of one billion dollars.

In Switzerland, a quarter of the costs for compulsory health insurance are incurred by medicines. Overall, medicines accounted for some CHF 10 billion covered by the compulsory health insurance scheme in 2023, a figure that is constantly rising.

Contrary to the claims made by Big Pharma and its lobby, the prices of new drugs and the exorbitant profit margins generated from them are therefore a driving force behind the explosion of healthcare costs in Switzerland. This applies in particular to patented products which, according to the Federal Council’s own admission, account for 75% of the costs of medicines covered by compulsory health insurance. While there are undoubtedly savings to be made from generics, the greatest potential of cost containment is in the area of patented medicines. But there is very little, if anything at all, happening here. And all the while, the costs of patented products are continuing to rise, causing our insurance premiums to soar, a trend that needs to be urgently contained. But, even though solutions exist, the Swiss authorities are loath to tackle this issue head-on for fear of antagonizing the omnipotent pharmaceuticals industry, which includes Basel-based flagship companies Roche and Novartis.

Pricing policy in Switzerland

In Switzerland, the compulsory health insurance system (or basic health package) only reimburses medicines that are registered on the List of Specialties (LS) and prescribed for authorised indications. The LS is established and constantly updated by the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH).

To be registered on the LS, a medicine must be authorized by Swissmedic, the Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products, and must meet legal criteria, such as efficacy, adequacy and economic efficiency (EAE evaluation). These conditions must be analyzed by the FOPH for reimbursement and be reviewed every three years. The request for the admission of a medicine onto the LS is submitted to the FOPH and each modification made to a medicine or its price should be subject to a new request for admission.

In general, the FOPH decides to admit a medicine on the LS at the request of the market authorization holder and after consultation with the Federal Commission of Medicines (FCM), which is composed of different stakeholders – i.e. industry, insurers, patients, doctors, hospital staff, pharmacists, federal and cantonal authorities. The FCM examines whether the medicine meets the criteria of efficacy, adequacy and economic efficiency. The FCM then formulates a recommendation for the attention of the FOPH, which also assesses these criteria, especially the economic efficiency. The FOPH makes the final decision on the maximum public price (or list price), based on two comparative assessments:

- a geographical comparison with the list prices in nine other reference countries (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom);

- a therapeutic comparison with other preparations used to treat the same disease.

Inclusion on the LS is thus an important step as it sets the conditions and level of automatic reimbursement for the product under the compulsory health insurance system. Reimbursement for a medicine on the LS is guaranteed, assuming all conditions spelt out under the “limitation” are met. Reimbursements for medicines not on the LS are considered under a separate legislative framework and are dependent on the random decision of each health insurer. Therefore, the decision whether to include a drug on the LS has major implications for access to medicines in Switzerland.

Secret discounts

At the World Health Assembly held in May 2019, Switzerland supported greater transparency on the prices for medical treatments (WHA Resolution 72.8). However, in contrast to these international commitments made, the revision of the Health Insurance Act (HIA) proposed by the Federal Council as early as 2020 (revision of the HIA, second package of measures) now provides for entrenching confidentiality about the prices of medicines in law.

With the arrival on the market of new and increasingly expensive medicines, especially for treating cancer, the FOPH has introduced what it calls “pricing models”. They are based on setting the terms and conditions for including medicines on the LS in order to allow for the speediest possible financial coverage of expensive treatments under the HIA. Indeed, this act stipulates in Article 32 that the services covered by basic insurance “must be effective, appropriate and economical”.

In other words, given the increasingly exorbitant prices being demanded by the pharmaceuticals industry for its newly marketed treatments, the FOPH has to negotiate a discount with them in the form of a refund to the relevant patient’s health insurance company (the most common model applied), of a maximum annual volume of coverage or of reimbursement in the event of treatment failure (pay for performance) to ensure that these medicines meet the required conditions stipulated by law and can be included on the LS and, therefore, reimbursed by basic insurance.

A policy of “fait accompli”

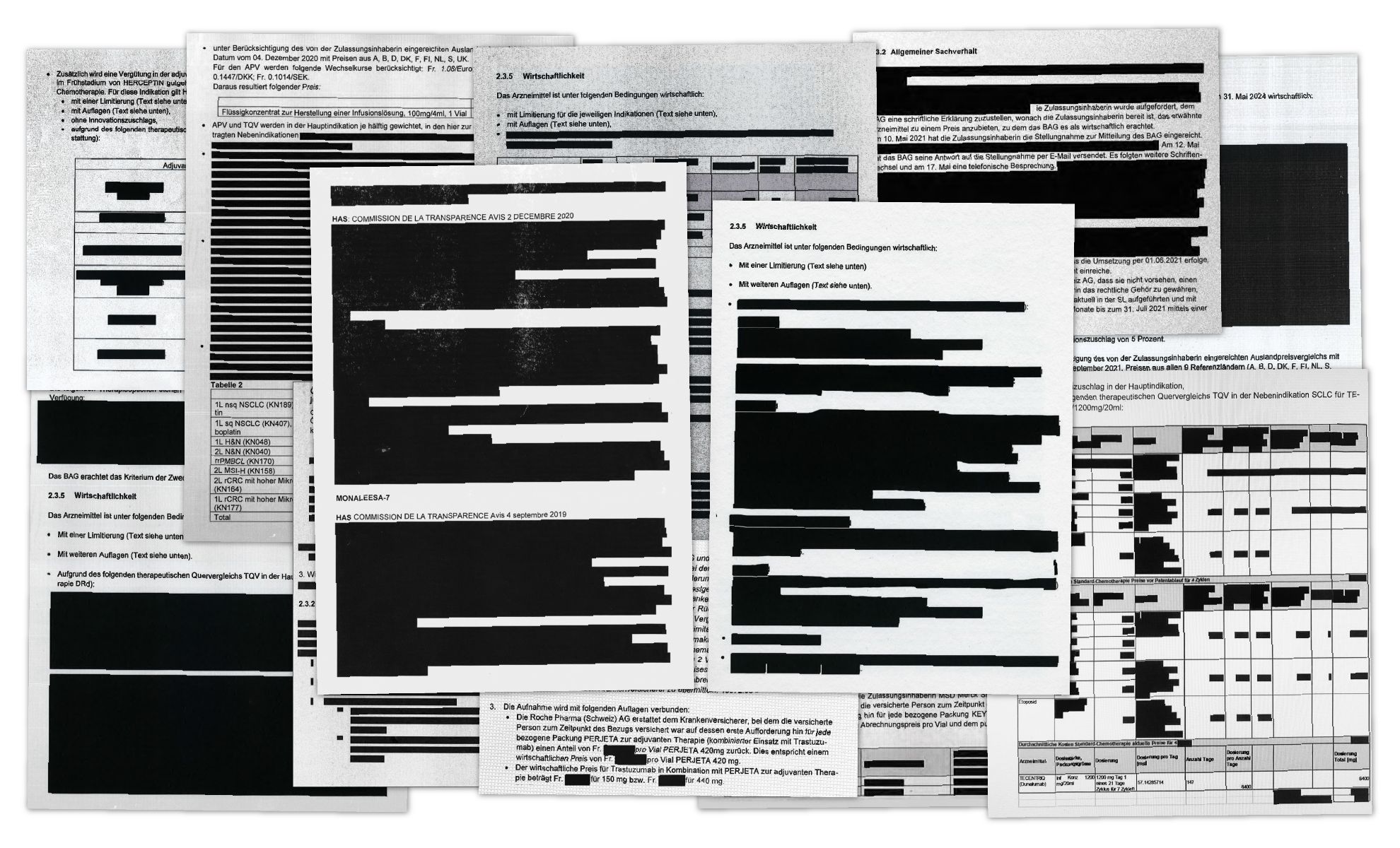

Pricing models are becoming all the rage in Switzerland. In January 2019, there were only around 20 such agreements in place; by the end of 2024, there were more than 180 pricing models covering 129 products – i.e. nine times more. Initially, these discounts were all published in the public LS database. In 2024, around two-thirds of products covered by pricing models are subject to secret discounts.

There was thus already a strong trend of the FOPH negotiating secret discounts before even the proposed amendment to the HIA had been accepted. The amendment was set to legalize a practice that is already common – a policy of fait accompli. The new element of the amended law will prohibit details about the amount of these discounts and the basis on which they were calculated from being obtained through a Freedom of Information (FOI) request – and therefore prevent us from knowing the net price of these medicines covered by health insurers. The principle of transparency would be sacrificed in the name of commercial policy, creating a dangerous precedent in the area of health insurance, rather than addressing the real problem: the imbalance in power and transparency of information. A real gift for the pharmaceuticals industry.

Healthcare costs are a problem in Switzerland, with an ever-growing number of people being hit by skyrocketing premiums. Due to this deliberate lack of transparency, Switzerland is once again protecting a system that helps multinationals maximize their profits, to the detriment of the right to health. In practical terms, the price set for medicines in Switzerland is used as a benchmark by more than thirty countries across the world, including some that are much weaker economically. So, if Switzerland raises the stakes in this, it is not only causing harm to its own population, but also to millions of patients abroad.

The power of pharma

Independent analyses identify the pricing power that pharmaceutical companies have as one of the main causes of the skyrocketing increase in drug prices. In Europe, price controls are a national prerogative, which means that each country then seeks to obtain the best possible “deal” as part of bilateral negotiations that are not transparent.

In this game, the pharmaceuticals industry definitely has the upper hand.

The first advantage is the high price obtained in the United States. Then, if necessary, they threaten not to market the product (or to withdraw it from the automatic reimbursement scheme) if the price demanded by the authorities proved to be too low - or even to go to court and very often win the case. Lastly, they disclose only the reference price (or “list price”), a fictitious amount used as a basis for the international comparison of prices between countries, but which does not correspond at all to the actual price negotiated with each state.

Despite the European countries’ efforts to join forces to negotiate better prices together (such as the “BeNeLuxA” initiative), it is clear that they are not competing on a level playing field. Governments cannot fight against this notorious “pricing power” wielded by the pharmaceuticals industry as part of the current pricing system.

In practice, confidential pricing models neutralize the government’s pricing mechanism and pit governments against each other. Independent studies and examples from abroad show that opaque prices and secret discounts do not guarantee quick access or long-term cost containment. On the contrary, faster reimbursement under compulsory health insurance opens up business opportunities and confidentiality increases the industry’s bargaining power.

Correcting the balance of power

Switzerland has a raft of other more effective ways available of achieving fair and equitable prices than secret discounts. It could, for instance:

- Bolster international collaboration (e.g. by fully joining the BeNeLuxA initiative)

- Reform the price setting process, starting from the investments actually made (R&D costs), including public subsidies, rather than setting the prices of patented medicines on the basis of ineffective, biased comparisons

- Take action against abusive monopolies by applying legal instruments recognized by national and international law such as compulsory licensing.

To actually do all this, however, would require the political courage to square up to the omnipotent pharmaceuticals industry and its lobby in Parliament and adopt the necessary reforms. Implementing merely an ineffectual measure such as confidential price models, which, if anything, is harmful and creates a dangerous precedent for democratic control, shows a sense of resignation on the part of our authorities. It is paramount that we change this situation if we want to be able to guarantee the financial sustainability of our system of fully inclusive coverage of healthcare costs, which is already in serious peril.